Juror Speaks Out Hours Before Execution in Death Penalty Case

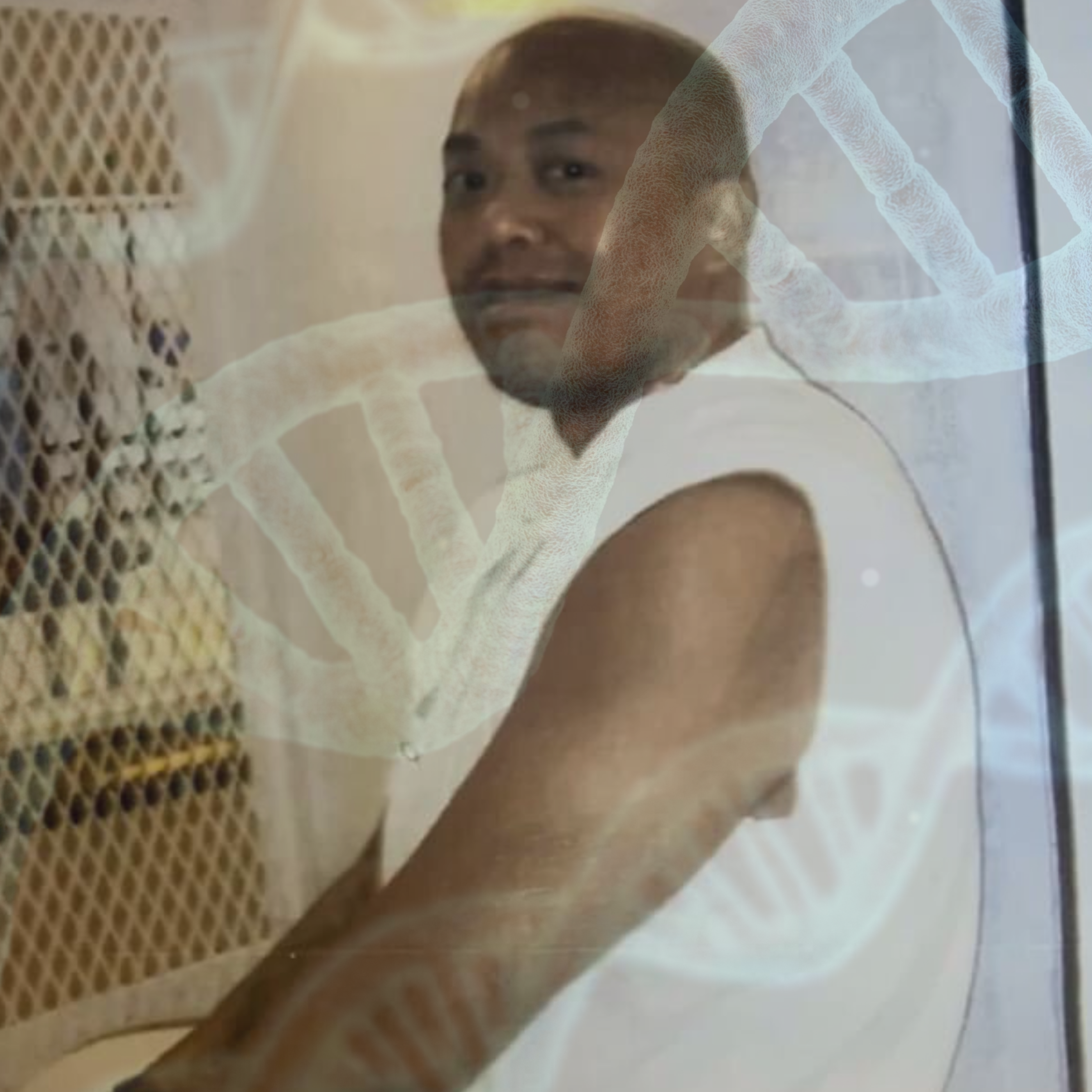

One of the people who voted to convict Kosoul Chanthakoummane said the condemned man’s appeal deserved to be heard.

Update 7:15pm: As noted by the media, including the Texas Tribune‘s Jolie McCullough, the execution of Kosoul Chanthakoummane proceeded as scheduled. “His mother watched him die,” McCullough reported.

Hours before Kosoul Chanthakoummane’s execution set for 6 p.m. August 17, one juror from the original trial told the Texas Observer that they still have faith in DNA evidence presented at trial—which linked Chanthakoummane to the 2006 murder of Dallas-area realtor Sarah Walker and is the main reason they cast their “guilty” vote in 2007.

But the same juror, who spoke to the Observer only hours before the scheduled execution, also said they believe that the issues the Laotian-American’s defense team has raised about that DNA evidence in last-minute appeals should be considered.

“If I was sitting on a jury … I’d want to hear what they were thinking and hear the argument about it and in turn, give the prosecution a chance to counter that testimony as well,” said the juror, who spoke on condition that their name not be published. “If those things were proven to be beyond a reasonable doubt, then, yeah, I would say that could put the conviction into reasonable doubt.”

Chanthakoummane also was convicted after prosecutors presented bite mark evidence and witness testimony by a couple who had undergone forensic hypnosis before sitting with a police sketch artist—two pseudo-sciences that have since been discredited and linked to wrongful convictions. But the juror told the Observer that for them, the most compelling evidence was DNA evidence that state prosecutors presented from the victim’s fingernails, which they said linked Chanthakoummane to the crime. In 2021, the Court of Criminal Appeals upheld the conviction on the strength of this DNA evidence.

“Studies on indirect DNA transfer demonstrate that secondary and tertiary DNA transfer can and in fact, does happen.”

In the most recent appeal, filed last week and denied earlier this week, Chanthakoummane’s lawyers raise two doubts about the DNA evidence: that it might have been transferred to Walker’s hands indirectly—Chanthakoummane doesn’t deny being in the model home where Walker was killed that day—and that it might not even point to him at all.

The juror said the original DNA evidence presented at trial in 2007 would have been enough for them to convict Chanthakoummane even without the bite mark and hypnosis evidence. But the jury wasn’t told about the new doubts raised by scientific advancements that occurred after the trial.

“I think DNA evidence is trustworthy if the samples that are collected are handled and tested properly, and they’re not … compromised in any way,” the juror said. “There wasn’t any evidence presented to us by the defense that said, ‘Hey, these DNA samples that were taken were mishandled, they weren’t tested properly, etc.’”

The latest appeal raises the possibility that Chanthakoummane’s DNA wound up on Walker’s hands after she touched something he had previously touched. One DNA swab was used to collect DNA from 16 different spots on Walker’s fingernails, so it would be impossible to tell whether Chanthakoummane’s DNA was found under her fingernails or on the top, according to the appeal.

“DNA and how it is interpreted changes and has changed since the trial.”

Simon Ford, a forensic DNA consultant tapped by the defense team to look deeper into how DNA was used during the trial, stated in a sworn declaration that “studies on indirect DNA transfer demonstrate that secondary and tertiary DNA transfer can and in fact, does happen. Thus, Mr. Chanthakoummane’s explanation is scientifically plausible, and indeed, it would be scientifically inaccurate to say the prosecution’s explanation is more plausible.”

The appeal also notes a new understanding of the complexity of analyzing “mixed” DNA samples, or samples that contain genetic material from multiple individuals. That was the case in the DNA sample that led investigators to Chanthakoummane—the swab from Walker’s fingernails showed evidence of her DNA and another person’s. Chanthakoummane and Walker were found to share multiple genetic markers, making analysis of the mixed samples even more difficult, according to Ford. The lab was unable to exclude Chanthakoummane from the sample. At the same time, the jury was told that it was “16.5 billion times” more likely that the DNA was a mixture of Walker’s and Chanthakoummane’s DNA than Walker’s and another person’s.

“DNA and how it is interpreted changes and has changed since the trial,” said Eric Allen, Chanthakoummane’s lawyer. “Yet another reason to halt this execution.”