Lady Bird Johnson Was About More Than Wildflowers

Using audio diary recordings, new book Hiding in Plain Sight brings the former first lady out of LBJ’s shadow.

Nearly 14 years after her death, Claudia Alta “Lady Bird” Taylor Johnson’s legacy, to most who know anything about her at all, has been boiled down to wildflowers alongside Texas highways. In Lady Bird Johnson: Hiding in Plain Sight, Julia Sweig makes the convincing case that Johnson’s role in history is far more complex, interesting, and significant, even central to many of the events of the 1960s that continue to shape our culture and politics.

An accomplished historian and journalist, Sweig makes full use of more than 850 audio diary recordings, comprising 1.75 million words, that Lady Bird made between 1963 and 1969. Holt Rinehart published a heavily edited volume of transcripts of the diary in 1970, but it was not until 2013 that the LBJ Presidential Library in Austin began releasing them publicly.

“Listening to and reading the contemporaneous accounts of her White House years, one finds in Lady Bird Johnson a prodigiously disciplined participant, actor, and witness to and student of history,” Sweig writes. “Hidden within the sheer scale and, at times, overwhelming detail of the diary are golden nuggets of insight about her husband and herself, the marriage they created, and the ambitions animating the presidency they together crafted.”

As the book’s title suggests, however, historians until now have failed to reckon with the diary and the insight it provides, causing them to relegate Lady Bird “if not to oblivion, then to the role of a diminished supporting actor in the sweeping narrative dominated by her husband,” Sweig argues.

Hiding in Plain Sight brings Lady Bird out of Lyndon Johnson’s shadow, moving him into the background as much as possible, despite the close union, joint aspirations, and political partnership that often led her to refer to “our presidency.” With only occasional exceptions to provide historical context, Sweig depicts LBJ from Lady Bird’s point of view, describing his mentality and decisions, his victories and falterings, and fateful turning points, in terms of Lady Bird’s perceptions of them and participation in them. Sweig mentions his frequent infidelities, for instance, merely in passing, a reflection of Lady Bird’s own near indifference toward them. He does not appear at all in many of the book’s chapters.

The book is exceptionally well executed: impressive in its thoroughness while disciplined in its focus, clearly structured and written, and most important, intimately insightful.

The portrait that results is of a woman with an extraordinary mind, remarkable expressiveness, understated charisma, and honed interpersonal skills—with or without Lyndon. A graduate of the University of Texas with degrees in both history and journalism, Lady Bird had the enviable ability to size up almost everyone she met, then use what she gleaned to strategically marshal relationships to the Johnsons’ benefit (skills she often used to manage her mercurial husband). She also was successful in business. Lady Bird played a central role in transforming Austin’s KTBC, which she and Lyndon bought with her family’s money in 1943, from a near-bankrupt radio station into the cornerstone of a multimillion-dollar fortune.

Sweig also provides plenty of examples of Lady Bird’s talent as a writer with a keen eye for detail, a powerful memory, and a poet’s gift for creative turns of phrase. She employed that talent not only extemporaneously in her diary but also deliberately in the speeches she helped compose for LBJ and as an advocate for her chosen causes.

Details drawn from the diary abound in the book, allowing Sweig to paint vivid scenes describing precisely what Lady Bird, her family, and her circle did, said, wore, and ate—including Lady Bird’s preferred weight-loss diet of boiled eggs and black coffee—at any time on any given day. Sweig opts for depth over breadth, focusing primarily on the diary, and therefore only the time LBJ was president. She provides, for example, only brief accounts of Lady Bird’s biography and other relevant background, as well as an epilogue summarizing Lady Bird’s 34 years after Lyndon’s death. Her scope thus narrowed, Sweig can go into more granular detail, to the point that some passages read almost like they came from a novel. I found myself wondering which actor could succeed playing Lady Bird in a film adaptation. (I thought of Kathryn Hahn; a friend suggested Kristin Davis or Laurie Metcalf.)

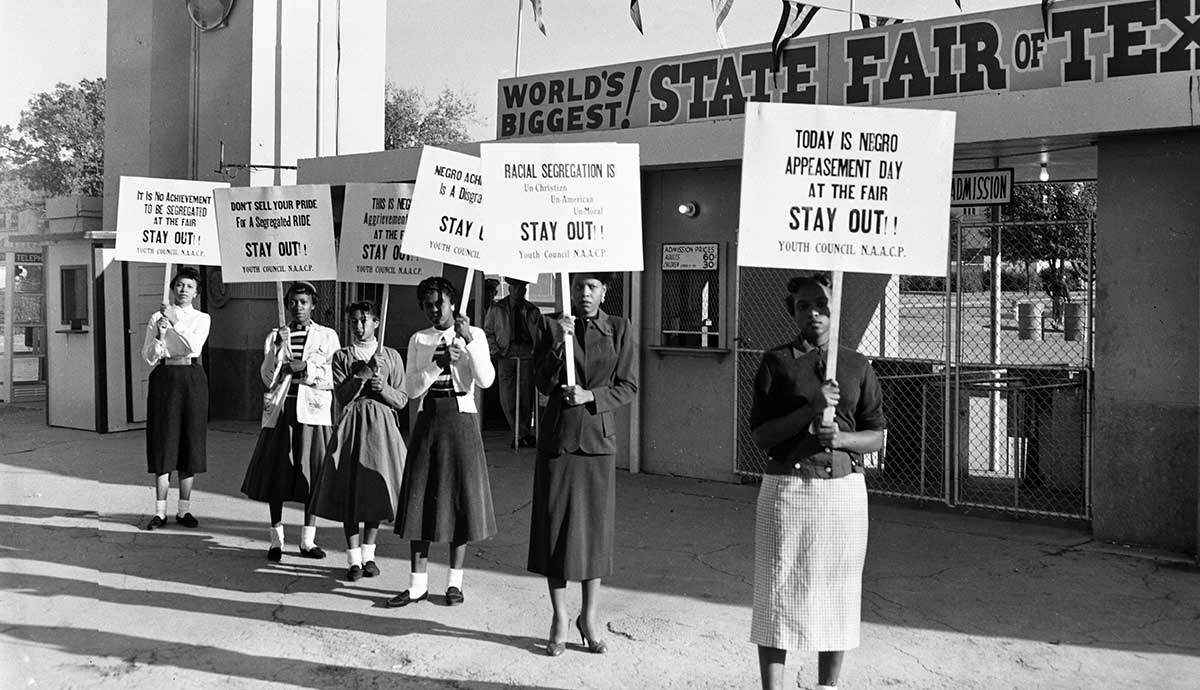

Much of the book is devoted to Lady Bird’s passion for “beautification.” It’s an unfairly diminishing term that belied Lady Bird’s sophisticated understanding of the burgeoning environmental movement and modern urban planning in the context of the era’s civil rights revolution. Lady Bird herself explicitly resented the reduction of her efforts to garden club-style flower-planting, but typically strategic, she used such projects as a Trojan horse to advance her broader agenda. She found like-minded allies in environmental preservationist Interior Secretary Stewart Udall and influential landscape architect and urban designer Lawrence Halprin, with whom she planned and fought for major improvements in the built environment, especially in Washington, D.C. One of the book’s main accomplishments is its rescue of Lady Bird’s reputation in this regard, breaking through the popular image of the wildflower lady to reveal a compassionate thinker deeply concerned with how Americans’ environments, broadly defined, foster freedom and well-being.

Sweig also points to Lady Bird’s pioneering feminism, showing her convening “doers luncheons” with leading women in business, politics, journalism, and the arts, as well as securing independent funding for her operation in the East Wing of the White House. Decades before Hillary Rodham Clinton declared she was not merely a typical “stand by your man” political wife, Lady Bird succeeded in walking a finer line, projecting a devotion to wife and mother roles—the only acceptable ones to many Americans at the time—while behind the scenes increasing her power and influence and supporting other women in expanding their own.

Hiding in Plain Sight also reports Lady Bird’s perceptions of the three assassinations—of John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr.—that in large part defined the era. Sweig includes plenty of material for students of the civil rights movement, including LBJ’s push for passage of the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act, and the war in Vietnam that ultimately drove him from the presidency and threatened the first family personally. (Both of the Johnsons’ sons-in-law were deployed there while Lyndon was president.) By doing so, it makes an important contribution to historical studies. Perhaps more important, it sets down for the first time the inner life and legacy of one of the 20th century’s most remarkable and significant women.

It’s an outcome, Sweig concludes, that Lady Bird would have found satisfying.

“Just as she appreciated the complexity of other public figures, starting with her husband, Lady Bird Johnson well understood—indeed, hoped—that at a certain point in history the breadcrumbs she left us would allow us to see, assess, and appreciate her place in American history,” she writes.

Hiding in Plain Sight thoroughly fulfills that hope, amplifying a voice that was muted for too long.