The Lonesome Writing Guru

How author Larry McMurtry—and George Getschow, editor of a new book about McMurtry—helped shepherd a Lone Star literary community.

The word “guru” fits George Getschow, a Dallas-based former Wall Street Journal editor, member of the Texas Institute of Letters, and director of the Archer City Writers Workshop. For years, George has encouraged and cajoled young journalists (and older ones) and other Texas writers of all types into writing their first books. But Getshow too had a mentor: Larry McMurtry.

At home, Getchow keeps a bookshelf stuffed full of the complete works of McMurtry, a legendary Pulitzer Prize-winning author who produced dozens of novels and nonfiction books, some of which became miniseries and movies like Lonesome Dove, The Last Picture Show, and Terms of Endearment, before his death in 2021.

McMurtry’s life and work spanned the state: He grew up at his family’s ranch in a remote spot known as “Idiot Ridge,” and taught at Rice University in the 1960s, when his home was a stop on Ken Kesey’s psychedelic bus tour. He roamed more as he gained fame and wrote screenplays for Hollywood but eventually returned to his hometown of Archer City, where he developed a sprawling bookstore and kept churning out at least five typewritten pages a day.

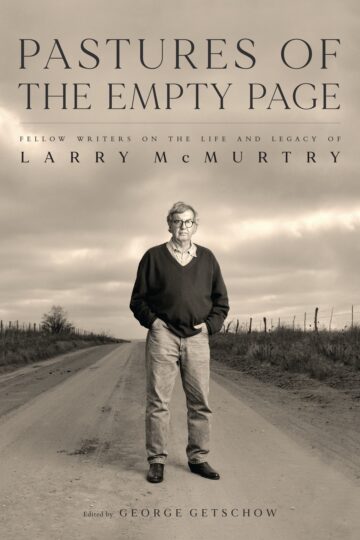

Along the way, McMurtry, though known as a curmudgeon, befriended and inspired many other Texas writers. And now Getschow has tapped a who’s who list of Texas authors for a new book about McMurtry: Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry (University of Texas Press, 2023). Contributors include master border storyteller and author Alfredo Corchado, Pulitzer Prize-winner Lawrence Wright, author Stephen Harrigan, true crime master Skip Hollandsworth, and novelist Sarah Bird, among many others.

The Texas Observer’s Lise Olsen recently interviewed Getschow about McMurtry.

How did you decide to edit this book?

I worked with Larry very closely for more than a decade, when we’d go to Archer City every year for a workshop for the Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Conference, and he became kind of a cheerleader. That’s kind of odd because so many think of [McMurtry] as tough or aloof but when it came to writers, he really always was encouraging.

Every year, we still have 20 writers at the Archer City Writers workshop—journalists, novelists, people from various walks of life who come to try to channel Larry as their muse. Now we’re talking about using the proceeds of this book to create a permanent writing center named in his honor.

There’s a long tradition of telling stories about people when they die—and this book came partly out of that, right?

I called for a convocation for him in Archer City a few months after he died. There was no public memorial service. Ten of the essays that writers read aloud in Archer City grew into the book.

Were there writers you asked to contribute who refused?

There were some people who felt it would be impossible to bottle up Larry McMurtry in an essay. They were intimidated. There were even some special and prominent writers that said, “George I understand where you’re coming from … but no matter what I would write, it would never measure up to what I feel about Larry, and I am afraid if I attempt that, it would make me too sad.”

Many Texas authors write about being influenced by McMurtry, even if he sometimes made them mad. One essay about McMurtry as a critic (and a champion) may have been the last thing ever written by Houston storyteller John Nova Lomax III, (the great-grandson of a famous Texas folklorist), before his death this year at age 53. Tell me about that.

I had known John for years and remembered he’d dubbed Larry McMurtry “the grand inquisitor.” John was a guy who appreciated Larry’s not having any sacred cows, and I remembered him talking about how much he admired Larry for taking on the revered, holy old-timers like J. Frank Dobie and Walter Prescott Webb.

In a way, Larry McMurtry was sort of our literary critic, and he was also tough on himself.

After Lonesome Dove came out, someone told Larry it’s the Gone with the Wind of the West. and he said “It ain’t no masterpiece.”

I thought John was the perfect person to write that essay since he too was a critic and a champion. … But it was really hard because he got sick shortly after that, and I wasn’t hearing back from him. Finally, I got in touch with his wife and she told me what was happening. I last talked to him when he was in a rehab center in a wheelchair, but somehow he finished the essay. It’s one of the best in the collection.

One of the few (and funniest) essays that was previously published comes from Oscar Cásares ( “Why Lonesome Dove Gives Me the Creeps,” which appeared in Texas Monthly) Casares describes being traumatized by an apocryphal scene where cowboys are attacked by a nest of swarming cottonmouths. McMurtry seems a master of the bizarre detail. His classic The Last Picture Show features a character who pushes a broom around a tiny dusty town that can never be clean (and includes a bestiality scene). Any other odd stories to share?

His powers of observation were incredible. This was a guy that the whole world was sort of his tableau. There was never a time when he wasn’t thinking out stories or working on stories.

One time we were talking about a book that we’d both read, and he was talking about a character I didn’t remember at all. He tended to fixate on things I wouldn’t even think about…

Larry wrote about people—some of whom were likable characters who didn’t like to work that much. Larry used to talk about how he’d sit around Archer City listening to a group of men who’d whittle all day. … Larry was able to write about people who liked to be idlers. And he was able to write about them in a way that they became fully engaging.

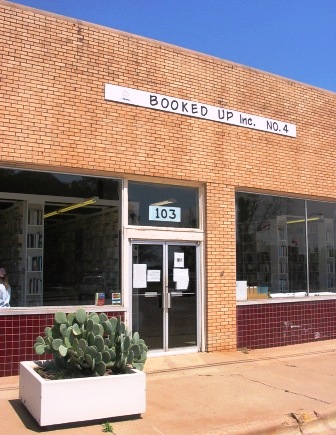

One of McMurtry’s legacies was being a bookman. His bookstore complex, BookedUp, in Archer City, at one time had 450,000 volumes. Why did he build a huge book empire in a tiny town?

He was both a master storyteller and master book collector and scout. That is rare. He had this vision to be a chronicler of small-town Texas and the American West and at the same time create a book town in his hometown. He used to say, “I grew up in a bookless town in a bookless part of the state.” And he created a book town.

Does the tale of how Larry’s home became a stop on Ken Kesey’s psychedelic bus tour come up?

Kesey and McMurtry were both Stegner Fellows, so they knew each other very well. Larry was more of a stuffed shirt. Kesey was a drughead and a wild man, but they were friends, and Larry (much later) married Ken Kesey’s former wife…

But he was raising his son James [James McMurtry later gained fame in his own right as a musician] in Houston when the Merry Pranksters showed up in 1964. He was a little worried about his son when this psychedelic bus pulled up—there was some wild woman who jumped out. I just think that’s sort of an example of Larry’s openness—Larry had writer friends of all ilks, including Ken Kesey. And, of course, that episode ended up in Tom Wolfe’s book.

You’re on tour now promoting the book and hope to use proceeds for the permanent new writing center in Archer City. The next stop is the Boerne Book Festival on Saturday, October 7. What’s the reaction been like?

The Dallas theater was jam-packed with about 100 people. Book People in Austin was packed. I just think there’s a huge thirst to learn about Larry McMurtry and what made him the writer that he was. … I didn’t realize before how ardent his fan base was. He called himself a “minor regional writer,” but I don’t think anyone else believed that. It was an honor and a privilege to assemble the voices of so many Texas writers who were moved by him and whose lives wouldn’t be what they were today if it wasn’t for Larry.