Teddy Maddux guides his green 2001 Ford Expedition along an open strip of asphalt between far-reaching rows of weather-beaten tents and plywood shanties. It’s a bright morning in mid-January. With a thick rust-colored beard and ready smile, the 45-year-old waves to residents who lounge in plastic patio chairs, tidy up their living areas, or cycle by on battered mountain bikes. Hitting the property’s southern border, he turns right, gliding by a covered patio and a row of gray porta-potties before reaching another stretch of ramshackle structures along the lot’s western fence line. In front of a tent-like portable carport, off-white and badly worn, he parks. This, for now, is home.

In a small, ersatz backyard, Maddux is growing nopales and green onions in a raised planter. Inside the vinyl garage, he’s hung a half-length mirror and photo print of the Conciergerie in downtown Paris. As he shows off each detail, he chuckles, with a hint of self-deprecation. “Humor helps you out here. If you can’t laugh about it, you’re gonna cry about it,” he says. On the asphalt floor, he’s placed a white plastic horse, a gift intended for a 9-year-old daughter he hasn’t seen in six years.

For the past 10 months, Maddux has lived at a 7-acre homeless encampment on state-owned land in far Southeast Austin. Opened by the Texas governor in late 2019 as part of a political spat with local officials, the site sits just off a major highway, wedged between a shuttered heavy equipment dealership and a mobile home park. Over time, the paved and treeless lot has transformed into a cacophony of ad-lib architecture.

Toward the front sit about two dozen connected garages, formerly used by the state for vehicle maintenance, now made into customized shelters. Doors with locks have been jury-rigged and front patios concocted; inside, furniture is arrayed beneath hanging string lights and decorated walls. Farther back begin the tents and shacks. Campaign signs from the 2020 elections now serve as fence panels and pseudo-insulation. One man has laid down artificial grass; another has built an arched entryway decorated with logs and moss.

The camp sounds like highway traffic and planes flying overhead to the nearby airport. With some frequency, it sounds like a person in the throes of emotional crisis, screaming at neighbors or the heavens. The place smells often of dust, sometimes of grilling meat, and anywhere near the porta-potties it tends to reek. In the summer, the ground bakes; year-round, the wind is hell.

For Maddux, the place has been a source of stability he lacked elsewhere on the streets, though it’s also where certain demons have caught up with him.

In late 2018, Maddux was released from prison after serving four years on an assault charge. Soon, he was living in Austin—about an hour south of his hometown of Rogers—at a halfway house. There, things went badly. “The alcoholism caught back up with me,” he says. Because sobriety was required, he was asked to leave the house in fall 2019. It’s then that Maddux became a statistic: The formerly incarcerated are 10 times more likely to become unhoused than the general population. Leery of street encampments, he kept to himself at first. He found a hiding spot beneath a tree beside an abandoned business.

Like many of America’s homeless, Maddux was employed. Each day, he’d ride his bike to work in the shipping and receiving department of a company that makes industrial glass structures. But, while incarcerated, child support for his daughter had snowballed to $27,000. Making his weekly payments of nearly $200 is a matter of pride: “I can’t stand deadbeat dads,” Maddux says. After a few months, he bought the SUV, seeking reliable transport to work and another option for sleeping. Between the child support and car payments, his wages amounted to little in a tight rental market. “I’m a felon, so that’s one mark against me,” he says, “and housing in Austin is crazy expensive.”

Through a chance encounter at a laundromat, Maddux learned of the state-run camp. The place’s looks startled him when he first arrived in March 2020: “I was like, ‘Man, this is Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome,’ and I’m out there looking for the thunderdome cage in the back,” he jokes. But he soon identified benefits. Here, he could park his vehicle without fear of getting towed. The state provided military field rations, and a nonprofit furnished shower facilities. Maddux also found ways to make himself useful. He began ferrying carless neighbors to stores so they could buy supplies, and he was elected to the camp’s five-person leadership committee.

“Sometimes I’m better at helping others than I am myself,” he says. “I want others to do well, and I can’t even do well myself, you know?”

Possessed of a self-diagnosed addictive personality, Maddux found a dark side at the camp too. Methamphetamine, dirt-cheap and cut with various additives, was readily available and widely used. He’d dabbled before, but now the drug caught hold of him. “I let it get out of control here lately; it’s been kicking my ass,” Maddux says. As he explains, speed can serve as a sort of perverse cure-all for life on the streets, providing energy for the chronically sleep-deprived, quelling hunger, and relieving feelings of stress, boredom, and shame. For Maddux—though he didn’t know it yet—the drug was also helping mask the symptoms of a brewing health crisis.

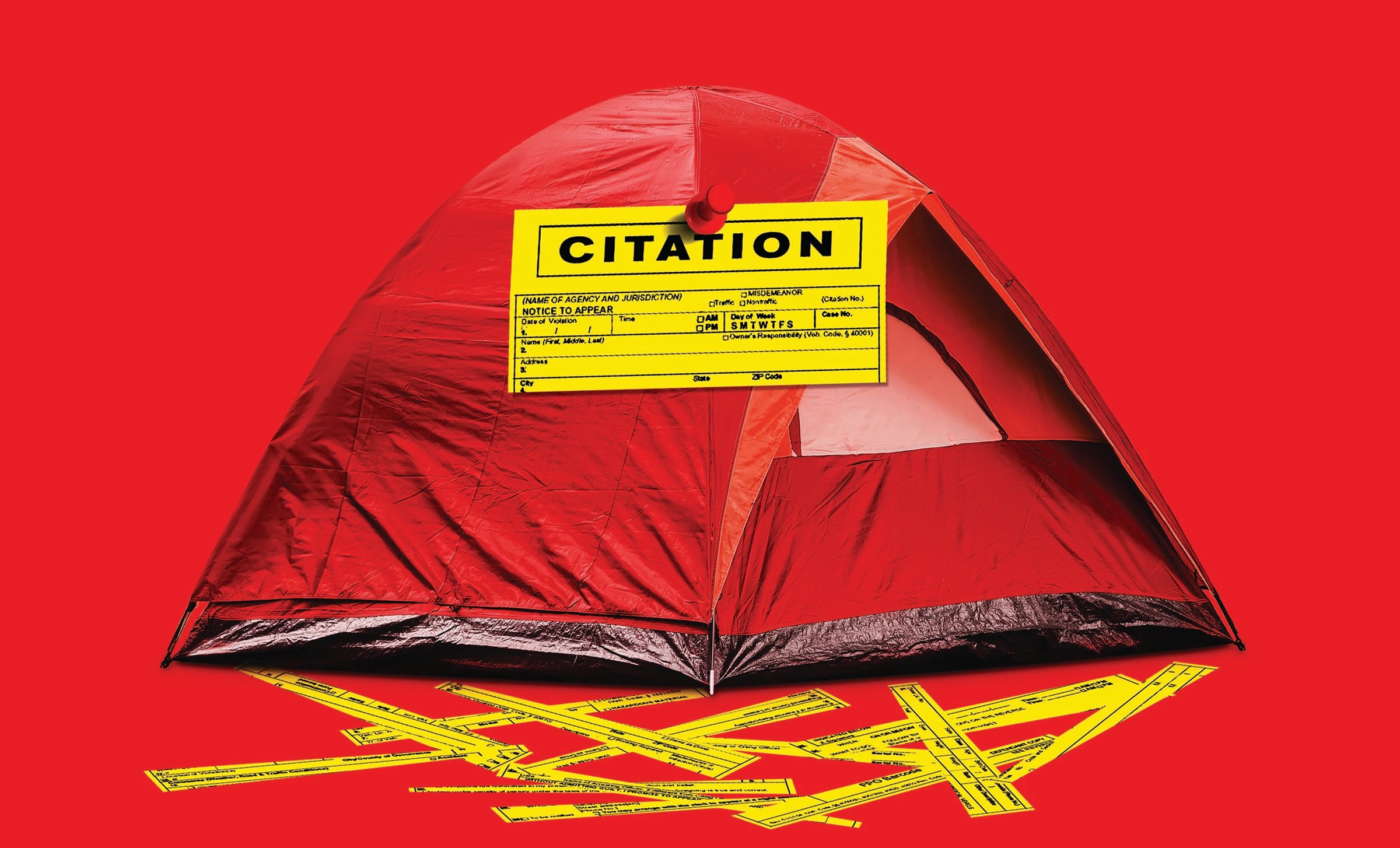

The state camp’s origins date back to June 2019. That month, the Austin City Council rolled back a 23-year-old ban on public camping, a rare decision in a country that’s increasingly criminalized homelessness over three decades. The move broadly permitted camping, with some exceptions. No longer fearing warrants and citations, Austin’s unhoused pitched tents across the city, largely in highway underpasses. Soon, a backlash raged. Republican Governor Greg Abbott, in particular, authored endless tweets bashing city leaders and smearing the unhoused as criminals. That November, Abbott ordered the state transportation department to clean out underpasses. Days later, without consulting local officials, he made the Southeast Austin lot available for camping.

Meanwhile, open-air homeless camps were proliferating nationwide, especially in ever-pricier urban tech hubs. A federal count last January recorded the largest unsheltered homeless population—those living in places like tents or cars, rather than traditional downtown shelters—in eight years. Many unhoused avoid shelters because of rules banning pets and segregating residents by sex. Responses to camps vary: Often cities tacitly allow them in undesirable areas, periodically sweeping them out if they grow too big; historically, a scarce few formally designate homeless campsites.

So-called sanctioned encampments, like that created by Texas’ governor, have been around for about 20 years in West Coast cities like Portland and Seattle. They can be short-lived or permanent, consist of tents or sturdier structures, and be run by residents or outside nonprofits. Like the Hoovervilles of old, they’re typically found on the outskirts of town. Austin likely hosts the country’s only sanctioned camp to emerge from a Republican’s attempt to spite a liberal city council, and, with some 200 residents, it may be the nation’s largest.

Advocates for the homeless tend to be wary of sanctioned camps, fearing they waste money that could go to permanent affordable housing. Cities also sometimes designate one site to justify clearing others, uprooting people who may be living near jobs then exiling them miles away. Experts say local governments that do sanction camps should carefully plan how long they will last and how to help residents progress to housing.

In Austin, the governor’s camp was spontaneous, and his only long-term plan cratered. A nearly two-hour walk from downtown, at the edge of a poor Latino neighborhood, Abbott’s camp was nowhere near existing homeless services, and there was no bus until the city added a line. The state provided troopers for security, toilets, and minimal rations—and that was about it. Fights erupted over the few available electric outlets. Still, campers trickled in: some fleeing the governor’s highway cleanups, others relocating from the nearby woods; some fresh out of prison, others leaving extended-stay hotels or other precarious arrangements.

Early on, Abbott allied himself with a coalition of downtown business interests calling itself ATX Helps, which wanted to stand up a 300-person mega-tent shelter on the property and hire a nonprofit to run it. But the group’s fundraising stalled out, and most of the camp’s residents loathed the idea anyway. After initial online celebration, the governor ceased tweeting about the site last February. Meanwhile, monthly state costs climbed to about $120,000.

Four months into the camp’s existence, COVID-19 seized the country. Nationwide, the pandemic forced traditional shelters to slash capacity, leading cities from Montana to Colorado to Kansas to sanction small encampments for the first time. Austin’s existing camps expanded into parks. Meanwhile, public facilities closed and charities scaled back operations, leaving many unhoused struggling to stay fed and bathed.

Into the breach stepped a small nonprofit called the Other Ones Foundation, whose main work had been hiring the unhoused to clean up city properties. The 4-year-old group, whose name is a Grateful Dead reference, rigged up a mobile shower trailer and started cycling through camps around town. At the state-run site, though COVID-19 cases were few—perhaps thanks to the open air and sunshine—staffers were struck by what one described as a “borderline humanitarian crisis.”

According to a June survey, more than half the camp’s residents were chronically ill and more than a third physically disabled. Theft and domestic violence were commonplace despite the troopers’ presence. Dozens of dogs had been born on-site, and some were habitual biters. Plus, everyone was frying in the summer sun. In August 2020, two middle-aged men perished in their tents. Autopsy reports attribute the deaths to meth and synthetic marijuana, but neighbors insist the heat played a role: Temperatures in some tents were approaching 120 degrees. The same month the men died, the Other Ones relocated its main office to the camp.

The nonprofit arranged for mail delivery and increased animal control. Its new office doubled as a lounge and computer lab. The organization attracted clinicians to provide general medical attention and helped some residents find permanent housing. It also convened community meetings, where residents renamed the site—previously called Abbottville or Camp RATT—to the Esperanza Community and elected a leadership committee from their ranks.

The Other Ones did little things, too, like providing hot coffee in the mornings. “That helps the mood of the whole camp,” says Norma, a pseudonym, sitting outside her tent in January. The 40-something native Austinite adds that thefts decreased once the nonprofit began offering work opportunities: “Before they got here, $5 was a lot of money.” Problems persist, Norma clarifies, but the group has softened some sharper edges of life at Esperanza.

In the wee hours of a February morning, Maddux finds himself in one of the gray porta-potties, slipping toward unconsciousness from internal bleeding. He staggers across the camp to an on-duty state trooper, who calls an ambulance. Awaiting help, Maddux passes out twice. At the hospital later that morning, he’s diagnosed with acute anemia, and soon enough, the doctors find the cause. Cancer, stage 3. Looking back, Maddux recalls symptoms dating to his final year in prison. But he never got checked out, he says, for fear of discovering the worst and of not being able to afford the treatment anyway.

A week later, Maddux is back at the camp. It’s 30 degrees out—and Texas is set to be ravaged by a five-day cold snap that will leave millions of housed residents without power or water, cause up to $300 billion in economic damage, and kill more than 150 people. Still drained from the anemia, Maddux is curled up beneath a blanket in his SUV, where he plans to weather the storm.

A half-foot of snow blankets the camp. Icicles descend from pallet fences. Flimsy tent poles crack beneath the weight.

Donald Montgomery, known at the camp as Hippie, dons a reflective vest and hard hat, then heads off to work. The cold isn’t bothering the 63-year-old much: Within his large vinyl tent, he’s erected another smaller tent for sleeping, and he’s kept a propane heater running. “This freeze has been a lot of added pressure on people who were not prepared,” he says. “For those of us who were prepared, it was almost no problem.”

Hyper-articulate, with long hair and a slight lisp, Hippie works part time at the camp as resident liaison for the Other Ones Foundation. Raised in rural Missouri, he once traveled the Midwest as a performer in the nation’s last regularly touring tent repertoire theater and later worked as an emergency medical technician. In recent years, health problems, including diabetes, have made it hard to hold a full-time job. He describes the Esperanza Community as “something new in the human condition … a safety valve for those who can’t and those who can’t right now.”

Through a thick layer of slush, he trudges across the camp to an old cinder block building, typically locked off, now converted into a temporary warming center. Two 18,000-BTU heaters, powered by a diesel generator, keep the space toasty. Hippie checks the generator, then assures someone is manning the desk inside, in case of emergency. His thoughts turn to the plight of housed Texans. “All those folks without power or water, they’re hurting,” he says, “and people with babies, oh my goodness.”

Not everyone, though, made it into the warming center. Multiple residents remember urging Justine, 60, to come inside. But she declined. Some recall her suffering recent episodes of disorientation. On February 15, she was found deceased in her tent, one of at least eight homeless Texans to lose their lives during the storm. An autopsy report confirmed she died of hypothermia.

In March, there’s a memorial for Justine at the camp. At a cluster of picnic tables, a man strums an acoustic guitar. A pastor from a church well-known to Austin’s homeless delivers a sermon. A small group of residents share recollections of Justine. The most vivid: She was among the camp’s earliest risers and was often seen leaving the back office juggling numerous coffees, which she delivered to older and disabled neighbors. “She always encouraged me every morning,” says one resident. “I’m still here and she’s not, but I think of her a lot.”

Chris Baker, founder and director of the Other Ones, then takes the floor. He mentions unhoused folks who died elsewhere during the freeze and some who lost extremities to frostbite. “We think this is criminal—that these are the conditions people have to live in simply because they don’t have enough money,” he says. “It makes me really fucking angry. … Goddammit, we can do better than this.”

Baker leaves the memorial and returns to the main office. Inside, camp residents clack away at keyboards or relax on couches enjoying an action film. A tattooed 36-year-old with dyed green hair, Baker takes a seat in a small corner room, then lays out the plan for transforming the camp into a place where no one dies in tents anymore.

The key, he explains, will be so-called microshelters—bare-bones tiny homes, roughly 100 square feet, with locking doors and air conditioning, safer than tents while still providing privacy. In a recent survey, most Esperanza residents said they liked the idea. Baker’s preliminary designs call for 200 tiny houses, split into four neighborhoods, to be built in the latter part of 2021. The structures would replace the current hodgepodge of accommodations. During the pandemic, microshelters have been deployed from California to Pennsylvania, but Baker can find no antecedent with the history or scale of his project.

“We’re stepping into the void,” he says. “This will be like a shelter-city.”

At the Esperanza Community, fire follows the freeze. Jesse “Cowboy” Clark awakes in the middle of an early April night to the smell of smoke filling the garage he calls home. Piles of clothing catch first, then the flames trickle up the wall and engulf the roof. Residents evacuate the 10 units connected to his. Six fire trucks arrive, beating back the blaze, but not before three of the garages are torched.

Cowboy thinks the fire started from a candle he lit before going to bed. The fire department report notes evidence of cooking, plus numerous extension cords running from a nearby breaker box, but doesn’t determine a point of origin. The report adds that “hoarder or near hoarder conditions” were observed.

“The shit caught so fast I’m lucky to be alive,” says Cowboy, 51, a few days later. He’s subdued—a rarity for a man whose booming laugh can usually be heard halfway across the camp. Raised in public housing in South Austin, he has roots near the camp about as deep as they come: His great-great-great-grandparents are buried in an old Freedman’s cemetery not half a mile away. Cowboy struggles to keep full-time work, he says, due to a “little bit of schizophrenia” inherited from his mom. Over a year and a half, he’d filled his spot with knickknacks and the snappy shirts and Stetsons he favors. “Now, I lost everything.”

Within days, the state transportation department, which owns the property and buildings, announces all the garages are coming down. The Other Ones hires camp residents to throw up temporary IKEA shelters for the couple dozen to be displaced.

On April 12, the first tear-down crews arrive. Beam by beam, they dismantle each garage with a specialized Gradall excavator. Former homes, such as they were, collapse. Trash abounds; mice flee the scene.

For some, despite the new IKEA shelters, the change is traumatic. On the last day of demolition, two residents refuse to vacate for part of the morning. “I wish I could do more to stop ’em,” says Margaret Post, 61, through intermittent tears. Post may be extra-sensitive to displacement. She’s been homeless since her trailer park, just down the road from the camp, was bought out in 2016 to make way for pricey apartments. Chain-smoking to calm her nerves, she reluctantly eases into her wheelchair, then leaves her place behind.

There will be more disruption at Esperanza. The new shelters are meant to give way to the sturdier tiny homes, and to get there, the Other Ones needs to lay sewerage and electricity the length of the site. For safety and liability reasons, the remaining homespun sheds and lean-tos have to go. Ultimately, the Other Ones—having grown from a staff of one to several dozen—will hold a long-term lease with the state and be responsible for everything from private security to case management. The site will serve as emergency shelter, meaning residents ideally move on to permanent housing within months; early estimates suggest costs will run a couple million dollars a year.

Thorny questions loom. How much decision-making power will residents have over community rules? How can crime be reduced without feeding people into the carceral system? Will the property stay open to all or be securely fenced off?

Though the nonprofit didn’t plan it this way, whatever answers the Other Ones finds may need to be an archetype. In May, after two years of political turmoil, Austin voters approved a ballot measure to restore the old citywide camping ban. If fully enforced, the ban could mean pushing some 2,000 people into jail, the woods, or shelter beds that don’t currently exist. The prohibition doesn’t apply, though, to sanctioned locations. Shortly after the vote, the city council convened to start identifying new sites for legal camps, a process guaranteed to spark neighborhood backlash. In a resolution, council members cited Esperanza as a model.

On a warm spring morning, Maddux sweeps the front porch of his house. Not the carport at the camp, but an East Austin duplex—with walls, windows, and a roof. His strength and wit have returned. Easing open the maroon front door, he plays tour guide. “Here we’ve got a laundry room, running water, a bed; no [wood] pallets anywhere in this house, I’ve done looked,” he wisecracks. “And over here, we’ve got awesome electricity … you ain’t gotta pour gas in a generator or nothin’.”

Maddux shares the two-bedroom unit with three roommates. But, for now, it’s free. Thanks to his diagnosis, a county-run health insurance program—which covers the homeless and certain other low-income residents—is paying for housing during his cancer treatment. Fifteen weeks of chemotherapy await him, and he’s wrapping up outpatient treatment for amphetamine abuse. He’s been clean for a few weeks, and through it all, he’s kept his job. He left his old carport with a couple whose tent collapsed beneath the February snow.

In retrospect, Maddux sees becoming homeless as a twisted sort of Providence. If he relied on health insurance through his work, he’d never be able to afford his treatment. “I didn’t understand why I got homeless; I do now,” he says. “And I don’t know if that is optimism or pure grace of God.”

He takes a seat at the kitchen table, where he’s left a mermaid-themed greeting card for the daughter he still hasn’t seen. “I sat down to write to her the other day, and I was like, ‘Man, I’m writing a stranger,’” he says. Apart from reestablishing visitation with his kid, his other goals remain murky. After his treatment, he could start paying rent to stay at the duplex, but he’d prefer a place with his own bedroom. He’s considering an RV park in the nearby town of Bastrop. “I don’t know if I can really afford housing in Austin,” he says. “Right now, I’m just taking it by feel.”

Despite the uncertainty, Maddux swears one thing: He won’t return to living at Esperanza. “I can’t go back to that,” he says. “I can’t go backwards.”

Maddux recalls the camp in contradictory terms. It’s a place where he saw people die, and a place that arguably saved his life. A place he fell into addiction, and where he climbed back out. A place often wretched, full of suffering and aggravation, and a place brimming with the sort of close-knit neighborliness absent from so much of American life. “At the camp, everybody that blows through that fuckin’ gate has some talent or some great personality, something in them that needs other people. It’s how humans are built. So they come in, and they find a niche,” he says.

“You could be at the bottom rung and no one else wants to tolerate you, and you’re welcomed there with open arms.”

As April turns to May, there’s a party. A local event production company has volunteered to arrange an evening of entertainment at Esperanza. Dozens attend, clustering around covered tables at the camp’s back end with plates of barbecue and pizza. Some residents have gussied up with nice hats or dresses. One of Willie Nelson’s daughters is there to perform with her band. To kick off the music, a handful of residents take to a temporary stage. One raps; one improvises a poem. Acoustic guitar in hand, Hippie steps up to deliver an original, his voice light and dulcet. “Don’t mind the hassle,” his song begins. “This, too, is gonna pass.”

Maddux is running late, but he makes it. Beaming, he bear-hugs Hippie, then Norma. He’s looking good, the treatments not affecting him much yet, and he even brags about putting on a little weight. Other former residents have come back too. Old friends razz one another; couples kiss. The sun moseys beyond the western woods, turning the scene rosy. In less than an hour, the peace will rupture: Halfway down the camp, a man will frantically hail an ambulance for a woman showing signs of a stroke. For now, though, everybody seems at ease. With a plate of food in hand, Maddux locates an open seat at a crowded table. “Man, I miss people here,” he says.