Listen to Survivors, Urges a New Book of Essays on Injustice

Lacy Johnson’s lyrical new book of essays grapples with sexual assault, environmental disasters and Donald Trump.

In one of the essays collected in her new book, The Reckonings, Houston writer Lacy Johnson recounts the ancient Greek story of Philomela, an Athenian princess who is raped by her sister’s husband, King Tereus. To prevent Philomela from revealing his crime, Tereus cuts out her tongue and throws her in prison. Philomela spends the next year silently weaving a tapestry that symbolically depicts the assault — purple threads against a white background — and manages to deliver the tapestry to her sister, who understands the message and frees Philomela.

The essay, “Speak Truth to Power,” is a meditation on all the ways men try to silence women. Often that silencing is achieved through terminology. “We call Andrea Constand an ‘accuser,’ a label we apply also to each of the dozens of women, individually and as a group, who have come forward to demand justice for being drugged and raped by Bill Cosby,” Johnson observes. “Our language shields him … transforms his crime into an allegation, a suggestion, a rumor.”

Johnson’s harrowing 2014 memoir The Other Side, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, describes her kidnapping, rape, and near-murder by a man with whom she used to live. The man is now living as a fugitive in Venezuela, where he married and had children; Johnson, now a professor at Rice University, writes about finding their family photos on the Internet. It took her 14 years to write about the assault. When the book finally came out, some men dismissed her account the same way many are now dismissing Christine Blasey Ford.

“What do I have to do to sell a memoir in this country, get kidnapped and raped?” a white male professor in Georgia asks a female colleague, in reference to Johnson’s book. The colleague later relays this exchange to Johnson, along with the man’s angry mention of James Frey, whose memoir A Million Little Pieces turned out to be heavily embellished. A lawyer from a women’s magazine running a story about The Other Side demands that Johnson send him the police file documenting her assault to prove it really happened. “I learn at this moment that there are some people who will believe I am lying about what men have done to my body no matter what evidence I present to the contrary,” Johnson writes. “I also learn it is not my responsibility to convince them.”

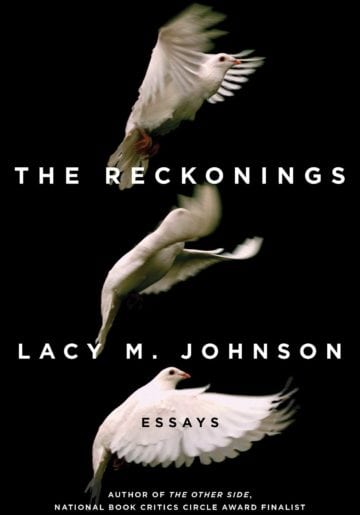

by Lacy M. Johnson

Scribner

$26; 336 pages Scribner

The 12 essays collected in The Reckonings form a kind of song cycle on the subject of justice, with recurring motifs and a basso continuo of moral urgency. Themes develop, intersect, change key. Individual essays address the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico; a nuclear waste dump in a suburb of St. Louis that is poisoning the surrounding neighborhoods; America’s gun culture; the election of Donald Trump; and Hurricane Harvey, which flooded Johnson’s west Houston neighborhood, forcing her family to evacuate. It’s a lot of ground to cover, but Johnson dexterously arranges these disparate topics into a larger unity.

The book opens with an audience member at one of Johnson’s book readings asking what she wants to happen to the man who assaulted her. What would justice look like? This question haunts the book: What would justice look like for the Gulf Coast fishermen who have lost their livelihoods? For the Missourians who develop rare cancers after years living next to nuclear waste? For the countless women whose sexual assaults have been downplayed or ignored?

The first step, Johnson seems to say in essay after essay, is acknowledging the impossibility of drawing a bright line between justice and injustice, good and evil. In her essay on the BP oil spill, she recalls reminding her creative writing students that nearly everything in Houston, including her own salary at the University of Houston’s Cynthia Woods Mitchell Center for the Arts (named after the wife of George Mitchell, the fracking pioneer), is ultimately paid for with profits from the oil and gas industry. No one is wholly innocent. During Harvey there was “no separating good water from bad. No separating water that might be drinkable from water that drowned a father, a police officer, the bat colony, a family of six, a factory, a Superfund site, the power station, the pretty woman who lived on the first floor of the apartment building.”

Similarly, Johnson writes in a remarkable passage, radiation is “around us always, and each of us is exposed to radiation daily … . We ourselves are a source of radiation, since each of us carries radioactive elements inside our bodies from birth. Throughout our lives, we are constantly irradiating one another, not only with charged microscopic particles but also with suspicion and fear and blame. We find infinite directions in which to project our rage and bewilderment and grief.”

In the Greek myth, as told by Ovid in the Metamorphoses, Philomela and her sister exact revenge on Tereus by killing the king’s son, chopping him up and serving him to his father as dinner. Enraged, Tereus is about to chase down the women when the gods finally put an end to the violence by turning all three into birds. But what interests Johnson most is Philomela’s tapestry — “this way of speaking out despite the impossibility of speaking.” Today, Johnson contends, “it is not enough that we speak our truth to one another in private or behind closed doors … We must tell anyone and everyone who will listen.”

The rest of us must open our ears.