Armando Carrillo had been waiting outside the Nueces County Jail for hours when he heard sirens approaching in the middle of the night on March 5, 2018. He had visited the jail earlier that day to see his youngest son, Danny, 27, who had been incarcerated for three weeks on a probation violation. Danny had sounded increasingly paranoid on the phone leading up to the visit and started crying and cowering when officers escorted him out of his cell. “You could tell he was losing his mind. I’ve never seen him like that,” Armando says. Pacing outside the jail later that night, Armando desperately called attorneys and bail bondsmen to help him get his son out. His stomach dropped when he saw an ambulance pull up to the box-like building lined with razor wire around 2 a.m. He thought of his son’s rambling last words hours before: “He was telling me, ‘I know I’m going to get killed.’”

Jail staff and people incarcerated with Danny said he seemed fine when he entered the lockup but eventually started spiraling—sobbing day and night, hallucinating, and babbling incoherently about threats against his family. Danny, who had been diagnosed with mental health and substance use disorders, had struggled in recent years—losing a sister and bouncing between lockup and halfway houses. His mother, who recently had brain surgery, had joined Armando to visit Danny that day but was detained by officers who uncovered an old theft charge when they screened her to enter. Guards said Danny became “belligerent” when she was taken away, then later swung at them when they stormed his cell to move him, striking one officer in the temple and another in the nose. Three guards then tackled Danny and pinned him to the floor, while a fourth stuck his knee into Danny’s back and a fifth shocked him with a stun gun. Nurses who arrived to check on him about 10 minutes later found him bloodied, without a pulse.

Hours later, officials released his mom. Danny, they said, was dead.

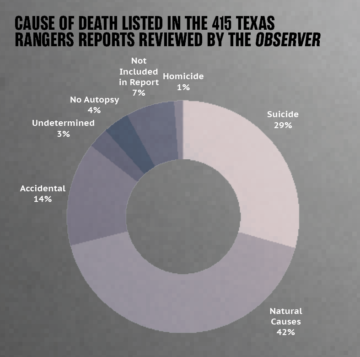

An autopsy ruled Danny Carrillo’s death a homicide, listing the cause as “sudden cardiac death during restraint procedures.” He is one of more than 1,100 people who have died in jail custody across Texas since 2010. Last year, the Texas Commission on Jail Standards (TCJS), which regulates county jails, counted 124 deaths, the highest number since the agency started recording them in 2009. Most deaths are among pretrial detainees, people who were never convicted of their alleged crime. In Texas, sheriffs are subject to outside investigation when people die in their jails. That job mostly falls to the Texas Rangers, the detective arm of state police.

As part of a months-long investigation, the Texas Observer reviewed more than 400 Rangers investigations into jail deaths over the past decade. The records show that state police regularly document jail conditions that can lead to preventable deaths, such as jail staff ignoring people with deteriorating health, taking hours to respond to emergencies, violently restraining detainees in the middle of mental health crises, denying treatment for chronic conditions like diabetes or heart disease, providing Tylenol for liver failure, and mocking people who are moaning in pain. These documents, together with jail inspection reports, state data, court filings, and medical records, show how Texas’ patchwork regulatory system repeatedly fails to ensure safe conditions behind bars. Records from TCJS show that more than three dozen jails, including the one in Nueces County, routinely fail to meet minimum standards in state inspections and in some cases have cycled out of compliance for decades—yet rarely face consequences.

The Observer identified dozens of cases in which the Rangers documented allegations of mistreatment including medical neglect, denial of medication, and abuse by jail staff. In at least 37 of the deaths reviewed by the Observer, the Rangers recorded evidence of jail staff actively dismissing signs of serious deterioration or cries for help. A man who later died of sepsis was accused of faking his pain and “just whining” by a jailer. In another instance, a nurse quipped that a man dying from a brain bleed was “just acting” and “should get an Oscar.”

The reports also show law enforcement taking people in medical distress—such as those who had been in a car accident, were tased by police, or were in the throes of a drug overdose—to jail instead of a hospital. For example, in roughly one-fourth of overdose deaths, the Rangers documented that medics cleared people for incarceration before they died. In at least 20 of the 173 deaths ruled to be from “natural causes,” the person had been hospitalized during incarceration, then sent back to jail—in some cases multiple times.

Of the 122 suicides, more than half involved people with documented histories of suicide risk, such as those who had previously attempted suicide or been placed on suicide watch at the jail. About 16 percent of those who died by suicide were on suicide watch and yet had not been checked by guards for more than 30 minutes—the minimum standard for suicidal or at-risk people detained in Texas jails. In 14 of the suicide investigations, the Rangers found evidence that jailers had lied about how frequently they conducted cell checks. The reports also show how existing regulations fail to save lives: In December 2019, a woman was booked into the Travis County Jail on an assault charge, after being hospitalized for cutting her own throat during a fight with her boyfriend. Jailers put her on suicide watch and looked in her cell every half-hour as required but didn’t realize she had opened the stitches in her neck until they saw blood on the wall.

While the Rangers investigations routinely uncover evidence of neglect and misconduct, they rarely result in consequences for jail staff, even in cases involving potential criminal activity. The Observer identified at least eight cases where the Rangers found evidence that jail staff had falsified logs of required cell checks or medical treatment records related to in-custody deaths—actions considered crimes under Texas law—yet local prosecutors declined to take them to a grand jury. Five cases reviewed by the Observer were ruled to be homicides, yet none resulted in charges. Four went to grand juries, which cleared the jailers involved. In the fifth, the Smith County district attorney declined to present the case of a man who died in April 2018 because a grand jury had already cleared the sheriff’s deputy who shot him during a traffic stop. The man required near-constant medical intervention for his gunshot wounds during his 10 months in jail, according to the Rangers investigation, and eventually refused medication, telling doctors, “I would rather die than live with this.”

Rangers documented their findings going to a grand jury in about a fourth of the more than 400 cases reviewed by the Observer. Charges were filed against jail staff in eight. The Rangers did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

With deaths in lockups on the rise across Texas and the rest of the country, reformers and jail regulators continue to urge state lawmakers to increase oversight and pass broader reforms to divert people from jail, particularly those with mental illness, who make up close to 40 percent of people behind bars. TCJS Executive Director Brandon Wood put the issue bluntly in a March meeting of the Texas Judicial Commission on Mental Health: “If we can’t have more of an impact and prevent our county jails from being the de facto mental institutions of our time, then I’m afraid that we’ll be seen as simply being like Nero, fiddling while Rome is burning.” The jail commission numbers undercount the lives lost: In a 2019 report, the agency said sheriff’s officials had skirted requirements to report and investigate deaths “on multiple occasions” by abruptly releasing people in medical crisis from custody just before they died. Wood didn’t respond to requests for an interview for this story.

This year, as COVID-19 spread rapidly in Texas lockups, exacerbating crises that predated the pandemic, Republican legislators passed a law backed by Governor Greg Abbott to limit jail releases and require cash bail for people accused of violent crimes. Opponents of the law fear it will lead to more pretrial detention and compound problems inside dangerous jails. Delays in court hearings during the pandemic have further crowded packed jails in places like Nueces County, which this spring began transferring people to jails in neighboring counties.

In 2018, when the Rangers arrived at the Nueces County Jail to investigate Danny Carrillo’s death, others incarcerated there were relieved. “I’m glad y’all showed up because everybody was talking like they’re just gonna slide it under the rug,” one man told them. “I know y’all are going to get justice. Y’all are Texas fucking Rangers.” Video interviews obtained by the Observer show how the Rangers’ investigation left out or downplayed their concerns. “If you get into it with a guard, they’re gonna come into the room and they’re going to fuck you up, as long as they’re not around the cameras,” one man told investigators, one of many statements that never made it into their report.

Others detained near Danny told the Rangers that jailers berated him before storming his cell and that the guard assigned to the cellblock that morning, Jesus Galvan, had a reputation for being cruel and taunted Danny before he was killed, according to interviews obtained by the Observer. However, Galvan faced easy questioning from Ranger Stephen West. Toward the end of his interview, Galvan told West, “You know, this is my first incident like this.”

“It’s par for the course, buddy,” the Ranger replied. “It’s to be expected. You’re gonna face some tough situations sometimes.”

Months later, a Nueces County grand jury cleared everyone involved.

The Nueces County Jail grappled with overcrowding, deficient mental health care, and violence in the years before and after Danny Carrillo’s death, according to Rangers reports, state inspection documents, complaints to the jail commission, and criminal court records. According to lawsuit filings, people incarcerated at the jail called one cellblock “the dungeon” and named one particularly violent guard “the punisher.” At least 11 Nueces County jailers have been criminally charged in recent years, with allegations ranging from brutality to lying about assaults in incident reports. Two of the jailers who restrained Danny faced charges for lying about a use-of-force incident that injured a woman at the jail months later; those charges were later dismissed. Three guards were indicted in another death at the jail that December, one of the eight cases reviewed by the Observer that resulted in criminal charges. Court records show the officers—accused of assaulting the man and photographing him naked, then lying about it—pleaded guilty in exchange for probation and no jail time.

Current Nueces County officials declined interviews or didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment for this story, including Sheriff J.C. Hooper. Former Nueces County Sheriff Jim Kaelin, who ran the jail for 12 years until November 2018, told the Observer he didn’t remember Danny’s death, one of three at the jail that year, saying, “That name doesn’t even ring a bell.” Last year, as chair of the Nueces County Republican Party, he pushed a conspiracy theory on Facebook suggesting George Floyd’s murder was a staged event. (Kaelin says he was just posting something that was sent to him by a retired Texas Ranger.) The former sheriff, who spent nearly three decades inside the Rangers’ parent agency, the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS), contends that deaths in custody are often unfairly blamed on law enforcement, saying those in jail, who tend to have higher rates of preexisting conditions, are a “volatile population when it comes to medical.”

“It’s OK to die anywhere in the United States, there would probably not be much of an investigation, unless you died in a jail,” Kaelin says. “If you die in a jail, there’s going to be a tremendous amount of scrutiny over that death, as if somebody did something, was negligent in the causing of that death.”

The Carrillo family sued the county and the jailers involved in Danny’s death, none of whom admitted guilt in a settlement agreement earlier this year. According to county records, it was the largest settlement following a death at the jail in at least a decade: $300,000, just over half of which went to the family after paying for attorneys fees. Months later, Armando still hasn’t touched the money. “It makes me feel like it’s blood money. I don’t know what to do with it,” he says. “If I could bring my son back, I’d give them back three times what they gave me.”

Sandra Bland cried throughout her time at the Waller County Jail, sometimes sobbing so hard that guards had a difficult time understanding her. She had just moved from Chicago for a job at Prairie View A&M University, a historically Black college and her alma mater. But on July 10, 2015, a Texas DPS trooper violently arrested her during a traffic stop. Guards later remembered that when Bland, 28, arrived at the jail, she insisted the charge against her, assaulting the trooper who pulled her over, was a lie, and “appeared to be in a state of disbelief about what was happening to her.”

Jail staff didn’t put Bland on suicide watch or any increased monitoring, though she told them she was depressed and had tried taking her own life the previous year. They did take note of the alleged assault on the officer, housing her in a cell alone “due to the aggressive offense she was arrested for.” Guards later said that Bland didn’t seem to be eating and made several frustrated phone calls in an attempt to make bail; she needed $515, but told jailers she was broke.

At 7:30 a.m. on July 13, 2015, jail staff rejected Bland’s request to make more calls, a Rangers report indicates. Less than two hours later, a guard found Bland hanging in her cell. The Rangers who investigated her death found two books in her bunk: 101 Ways to Find God’s Purpose in Your Life, which was closed, and a Bible that had been opened to Psalms 119. Blessed are those whose ways are blameless, who walk according to the law of the Lord.

Bland’s treatment at the hands of Texas law enforcement became a national scandal that increased attention on police violence, racial profiling, and negligent jails. Black people, who are overrepresented in lockups across the country, comprise 13 percent of Texas’ population but 28 percent of deaths in county jails over the past decade. In 2016, Bland’s family settled a wrongful-death lawsuit against state and local officials for $1.9 million and an agreement by the Waller County Jail to increase guard training and adopt an automatic electronic cell check system. The next year, the Texas Legislature passed a reform bill bearing Bland’s name that required law enforcement to collect more data on traffic stops and “make a good faith effort” to divert people with mental illness or substance use problems into treatment instead of jail. The Sandra Bland Act also strengthened mental health screening and training requirements for jailers and mandated independent investigations of county jail deaths, instead of allowing sheriff’s offices to investigate themselves.

“Connecting some actual reforms to this, it mattered to me. God it mattered to me,” says Cannon Lambert, the attorney who represented Bland’s family. “I did not want a number. It had to be something different.”

Texas lawmakers first established safety standards for jails in the late 1950s but provided no way to enforce them. The state health department was tasked with inspections but wasn’t funded to do so until more than a decade later, at which point it found nearly every Texas jail in violation. Still, little could be done.

At the end of the civil rights movement, people incarcerated nationwide began to fight back in court. From New York to Texas, they organized class action lawsuits to demand better, safer conditions. In 1972, a prisoner named David Ruiz filed a lawsuit alleging brutal treatment inside the Texas Department of Corrections, which ultimately led to federal court monitoring of the state prison system for decades. The same year, Lawrence Alberti, incarcerated in Harris County Jail, filed a lawsuit alleging that severe overcrowding had created a violent atmosphere and squalid conditions, which also led to long-term federal court monitoring of Harris County’s jail and criminal legal system. The lawmaker who authored legislation to regulate jails later described ones he visited in 1973 as “out of the dark ages,” according to an article in the Texas Bar Journal: “A bucket and a padlock were all the sanitation and security some of them provided.”

The mounting lawsuits against sheriffs and counties were a piecemeal, expensive way of bringing individual lockups in line. So in 1975, the Legislature passed a bill to create the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, described by a lawmaker involved as “a shotgun wedding between the Sheriffs’ Association and the ACLU with the State Bar of Texas as ‘matchmaker.’” By then, 40 percent of sheriffs or commissioners courts in Texas were tied up in lawsuits.

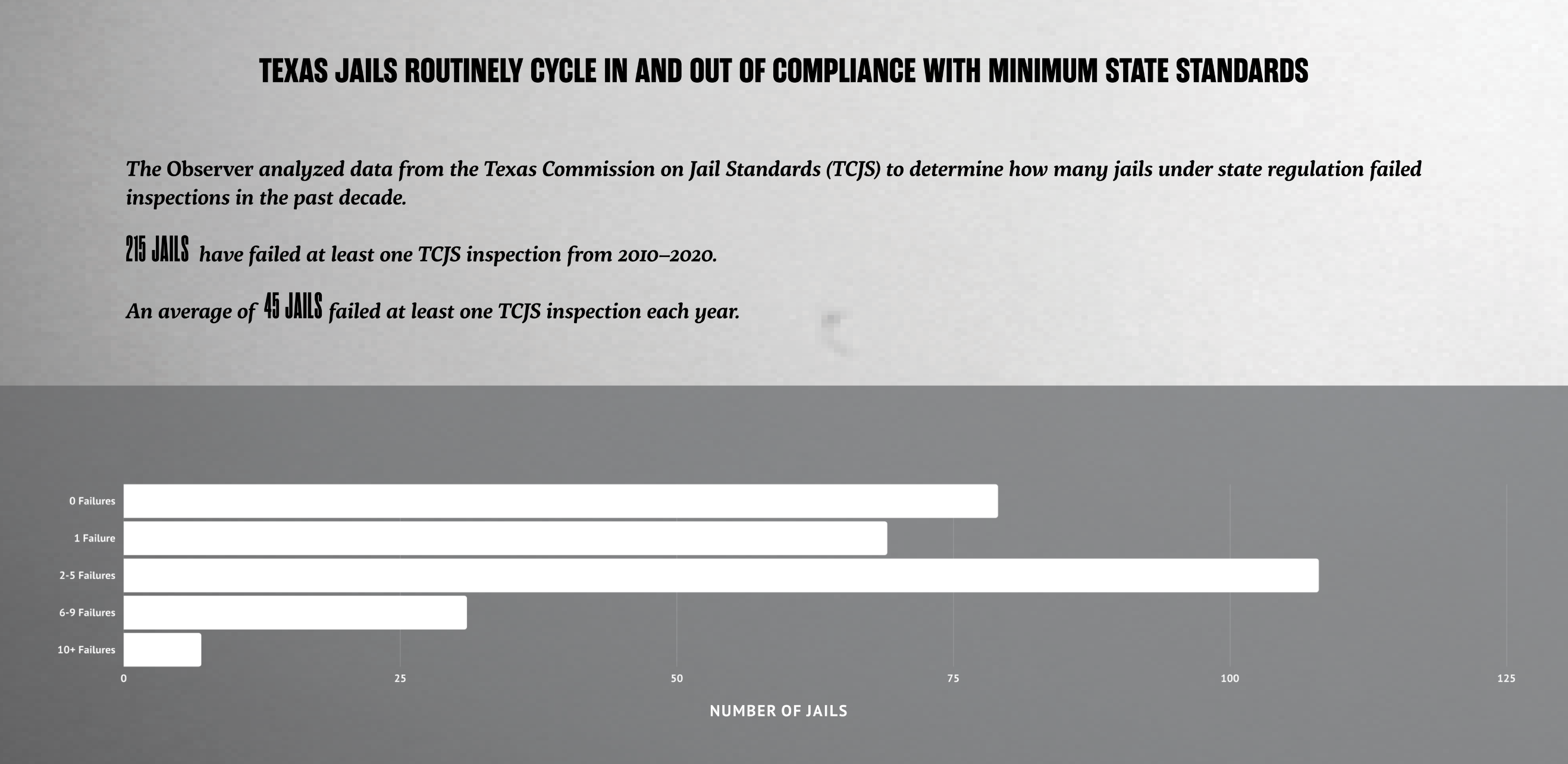

The number of people held in Texas jails has exploded by more than 500 percent since the 1970s—today, about 1 million people churn through the lockups each year. But TCJS has changed little in that time, perennially hampered by a shoestring budget and short-staffing. The commission’s $1.4 million budget has supported only three or four inspectors in recent years, the same number as decades before. In the 58-county inspection region that includes Nueces County, one person inspects 93 jails that detain more than 16,000 people.

Attorneys, advocates for jail reforms, and even the Texas Sunset Advisory Commission, the state’s watchdog agency, say that scant resources and limited enforcement power perpetuate a cycle of noncompliance. TCJS not only allows jails to resolve violations slowly, it also fails to hold repeat violators accountable, the Sunset Commission warned lawmakers this year. About 100 counties received at least one notice of noncompliance from TCJS from 2017 to 2019; of those jails, nearly half received two or more. The Harris County Jail, the largest in Texas, saw six noncompliance notices during that time; four of them cited staff for failing to properly monitor high-risk detainees.

The Nueces County Jail, where Danny Carrillo was killed, highlights larger regulatory failures that allow jails to remain dangerous. Inspection records show that TCJS found the jail in violation every year since it began inspections in the late 1970s until 1991, routinely citing the sheriff’s office for understaffing and for failing to adequately screen and classify inmates. Inspection records detail similar problems for the next 30 years as the jail cycled in and out of compliance: unsanitary conditions like mold on the walls and ceilings, broken toilets and showers, and water dripping into cells. The jail has been flagged for overcrowding numerous times, including as recently as this year, sometimes keeping people in temporary holding cells for several days beyond the 48-hour limit, and stuffing detox cells well beyond capacity.

In February 2010, guards left a man who’d already attempted suicide once inside the jail unmonitored in his cell for almost half an hour, during which time he hanged himself. The man had recently been taken off suicide watch, where he was checked on every 15 minutes, and was left without increased monitoring even after he’d expressed suicidal thoughts to a guard, according to the Rangers investigation. TCJS inspections following the death cited the jail for deficiencies regarding mental health and suicide screening, as well as failing to appropriately monitor potentially suicidal people. The jail passed a follow-up inspection in March, was cited again in April for failing to monitor suicidal and other at-risk inmates, then passed again in July.

Later that year, in October, Gregory Cheek entered the Nueces County Jail after suffering a psychotic episode that resulted in an arrest for criminal trespassing. His mother, Katie Cheek, says Gregory had stopped taking his medications for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and was wandering the streets homeless. Katie was relieved after a judge ruled Gregory incompetent to stand trial and ordered him into treatment at a state psychiatric hospital. Katie figured it was better for him to wait for a hospital bed while in jail than on the street. “At least he’ll be safe,” she recalls thinking. “We actually had put our faith in them being his ‘protector.’”

Gregory spent three and a half months in jail but never made it to the state hospital. People incarcerated nearby described him wasting away mentally and physically. They told the Rangers that guards took away Gregory’s clothes, bedding, and mattress after he tore them up and ate them, leaving him naked as the temperature outside dropped below freezing. Jailers interviewed by the Rangers described him as “an extremely disruptive prisoner who had mental health issues.” His legs began to swell and “seep,” but he wasn’t given adequate medical treatment, according to a lawsuit that was filed by his parents and later settled with the county. A jail nurse told the Rangers he discovered Gregory unresponsive with a forehead temperature of 74 degrees on February 6, 2011. He died at a hospital in the early morning on February 7 of a bacterial infection. TCJS noted no deficiencies at the jail that year.

Incarcerated people and their loved ones file thousands of complaints with TCJS alleging dangerous conditions inside Texas lockups every year, but the complaints rarely lead anywhere. Records obtained by the Observer show that the agency often closes cases by saying that medical complaints and criminal allegations, such as physical abuse by guards, fall outside its purview. The agency forwards all complaints to local jail administrators, whose responses range from blanket denials to defensiveness. Occasionally, TCJS forwards complaints to law enforcement agencies, including the Texas Rangers, but it’s unclear if they take action on them.

Nearly half of the Rangers’ 622 investigations in the past decade were opened after January 1, 2018, when the Sandra Bland Act’s requirement for outside investigations went into effect. But according to the Rangers, they were not given additional funding or resources to handle the workload. The investigations reviewed by the Observer range from more than 100 pages to just two. Reports about deaths in the Tarrant County Jail—which have spiked in recent years, with three in the same week in June 2020, three in September 2020, five in December 2020, and three in February 2021—averaged about four pages, even as they document cases where people died after being pepper-sprayed, tackled, and strapped into restraint chairs by guards.

In some cases reviewed by the Observer, Rangers failed to document even basic information, such as a cause of death. Sometimes, they didn’t talk to witnesses or appeared to simply write up internal findings from the sheriff’s office without further investigation. A recent New York Times story on Rangers investigations into in-custody deaths found numerous flaws, shortcuts, and missteps that illustrate the same pro-police bias that such investigations are commissioned to absolve.

Read here for more on the documents and data that were used to report this story.

The Observer identified nearly 20 cases where the Rangers found evidence that jail staff had falsified records but weren’t charged. That includes the Rangers investigation into Bland’s death, which showed that guards documented checking on her every hour as required by Texas law, despite surveillance video proving they left her unchecked for nearly two hours before she was found—a potential felony for tampering with government records, the most common criminal charge in the Observer’s review. A grand jury declined to indict any jailers involved in Bland’s death. The trooper who arrested her was fired and indicted for perjury, but the charge was later dropped.

Though Bland’s death prompted more Rangers investigations, Lambert, the attorney for her family, says it also underscored their limitations. “Let’s just be honest: They’re not independent,” he says. “An independent review would mean that someone is brought in with a fresh set of eyes with no agenda and is going to follow information wherever it goes. But there is a real brethren in law enforcement. … It blocks their ability to get to the truth in some ways.”

J. Joseph Mongaras was already on his way to the Kaufman County Jail, southeast of Dallas, when he got the call. It was May 19, 2019, and Mongaras, a criminal defense attorney, was driving to visit Elmer Dale Barrett, a 70-year-old Air Force veteran who was in the custody of the U.S. Marshals Service on drug charges and being held in the county jail. Barrett didn’t flag significant health concerns in screening forms when he was booked that February, noting instead that he worried about who would care for his 18-year-old dog. But Mongaras, his court-appointed attorney, knew Barrett’s health had deteriorated during his three months in jail and hoped his presence might convince jail staff to give Barrett medical attention. If they didn’t, Mongaras planned to push for a new hearing to get Barrett released.

But Mongaras never saw him again. When he answered the phone, he learned that Barrett had died early that morning.

Starting in March, Barrett had filed at least four written requests for medical attention. His handwriting grew more cramped as time wore on, and his requests were denied. On May 2, he complained of dizziness, but jail medical staff believed this was “an act” to go to the hospital, the Rangers investigation shows. On May 5, he said he had been having slight strokes and couldn’t feel the left side of his body; “I need to see somebody ASAP please,” he wrote. On May 7, he said he’d had a stroke or heart attack; on May 16, he said he had a stroke and needed to go to the hospital, telling staff he was “going to die in here.”

Barrett died on May 19, 2019, of complications from a heart attack that “may have happened approximately three to seven days prior to his death,” according to the Rangers investigation. Several days later, Mongaras received a letter Barrett had sent from jail. “I need a PR bond or something so I can stay at home so I can take better care of myself, it’s obvious they can’t do that here,” he wrote, asking about a lawsuit against the jail. “They really didn’t care if I died here on the floor.”

After Barrett’s death, TCJS found the jail out of compliance for what essentially amounted to a paperwork error: Medical tests ordered by the physician on May 7 were not sent to the U.S. Marshals for approval until more than a week later. In July, TCJS deemed that staff had been trained and the issue resolved.

Barrett’s death, like more than half of all deaths in Texas county jails in the past decade, was blamed on “natural causes”—a term that includes anything from heart attacks to late-stage cancer to COVID-19 to complications from withdrawal. More than 70 percent of those “natural” deaths were people younger than 60, according to data from the nonprofit Texas Justice Initiative. About 10 percent were people under 30 years old. The denial of medical care in correctional facilities is considered a form of cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment. Yet the Rangers investigations reviewed by the Observer documented dozens of seemingly preventable “natural” deaths like Barrett’s and Gregory Cheek’s, which appear to have been caused or exacerbated by conditions in lockup and denial of medical care. In both cases, the Rangers investigation was brought to a grand jury, which cleared staff of any criminal wrongdoing.

Krishnaveni Gundu, co-founder and executive director of the Texas Jail Project, spent months after Barrett’s death collecting information, hoping his family might file a lawsuit. She worked with Barrett’s close friend Lauren Halbert, who received phone calls and letters from Barrett in jail. A suit was never filed; the two-year statute of limitations passed in May.

Gundu still has trouble talking about Barrett’s death. It sticks with her even amid the countless stories of trauma and neglect she hears from other loved ones of incarcerated people. “I think it really gets me because it was so clear where the liability was. It was so clear who dropped the ball,” she says. She worries about Halbert, who was recently incarcerated in the Smith County Jail for a substance use charge and struggled to get help for her own medical issues. Halbert cried as she spoke on the phone in the jail about the guilt she feels that she couldn’t do more to help her friend. “It shocked me pretty bad losing him,” she said. “It’s kind of one of the reasons, I think, why I’m here. … And now I know exactly what he went through.”

On paper, Texas is one of the best states for jail regulation, says Michele Deitch, a University of Texas at Austin professor and an expert on prison and jail oversight, but that’s a low bar. Twenty-one states have no regulatory or oversight body for jails at all, according to a study she published last year. Some don’t even track deaths behind bars. But in Texas, regulations haven’t ensured safe conditions, in part because that was never really the mission, she says: “The motivation behind jail standards is ‘Keep us out of litigation,’ not ‘Help us get as good as we can be.’”

Deitch says debates over how much money jails need to improve conditions must be tied to a larger conversation about reducing mass incarceration. “While we’re waiting for facilities to shut down and all these changes to be made in society that will allow that to happen, you can’t ignore the needs of people who are locked up because they’re suffering,” she says. Currently, jail regulations do little to address broader issues with treatment or culture. “The most common sentiment we hear from people is how they’re not even looked at as human beings,” Gundu says. “Your safety doesn’t matter. You don’t matter. … As soon as you go in, you just don’t count.”

At least 10 people have died at the Nueces County Jail since Danny was killed. That includes one man confined to the same cellblock, who spoke with the Rangers hours after Danny died. He told them Danny was struggling with hallucinations and that he tried to comfort him by saying, “Pray, just pray that it’ll go away.” Guards found the man, 65, dead in his cell from heart failure nearly five months later. People incarcerated with him told the Rangers that he, too, had struggled to get medical treatment.

A lawsuit filed in September against Nueces County and the jail’s contracted medical provider at the time, Wellpath, says that Anthony Thompson, 50, wasn’t given insulin during his 72 hours in jail in 2019, though he told jailers he was diabetic on at least three medical screening forms and also called his mother, whom he lived with, about his medication when he was booked. His brother, Joshua Wayne Smith, says Thompson always kept his diabetes under control, taking his insulin regularly. But after three days in jail for a DWI charge, Thompson died from diabetic ketoacidosis, according to an autopsy report.

Complaints of medical neglect in lockups often land at the feet of companies like Wellpath, the country’s largest for-profit medical provider for jails. Wellpath treated people at the Nueces County Jail from 2015 until late 2020. Lawsuits have accused Wellpath of deadly care in lockups across the country, and a recent CNN investigation found that it failed to train workers and adequately staff facilities. The Rangers investigation into Thompson’s death found that he was also denied medicine to help with alcohol detoxing because the jail didn’t have any; Wellpath employees who failed to share information from his medical screening forms with one another blamed a software error.

Last August, the Nueces County District Attorney’s Office told the Rangers they could close their investigation into Thompson’s death “due to his death being a result of natural causes.” Nueces County DA Mark Gonzalez didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

“The notion that a person could be arrested for a class A, class B misdemeanor and lose their life because someone chose not to follow basic processes in medical administration is unconscionable,” says Matt Manning, the attorney representing Thompson’s family, who was previously second in command at the Nueces DA’s office. “A DWI is not a death sentence. It is not a capital crime in the state of Texas.”

Smith describes his older brother as his “protector” growing up, stepping in whenever he saw him getting bullied at school. Thompson was a father of two and grandfather to four. Smith says his brother tried to stay positive despite tragedies in his life, like losing his wife at an early age. “He was the glass-half-full jokester.” While he mourns the loss of his brother, Smith is also furious about how he died. “It’s just pure neglect and lack of concern for another human,” he says. “If he were at my mother’s, he would still be alive, because he would have gotten his medicine. Now my mother lives alone.”

If you or someone you know needs help, call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

This story was made possible through the support of the Fund for Investigative Journalism.