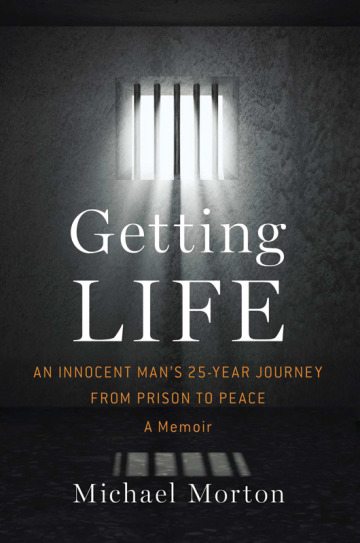

Michael Morton Chronicles His Fight for Freedom in Getting Life

A version of this story ran in the October 2014 issue.

Michael Morton will discuss Getting Life at Blue Willow Bookshop in Houston on Wednesday, Oct. 15, at 7 p.m.

Humans share a deep hunger for fairness, if not necessarily a knack for cultivating it within our social infrastructure. Compelling research from biologist Lixing Sun and others even suggests that our yen for fairness is an instinct rooted in DNA—a conclusion that should have kids on the playground nodding right along with evolutionary psychologists. This fundamental yearning for fairness is why wrongful imprisonment strikes many of us as one of the most horrifying fates imaginable.

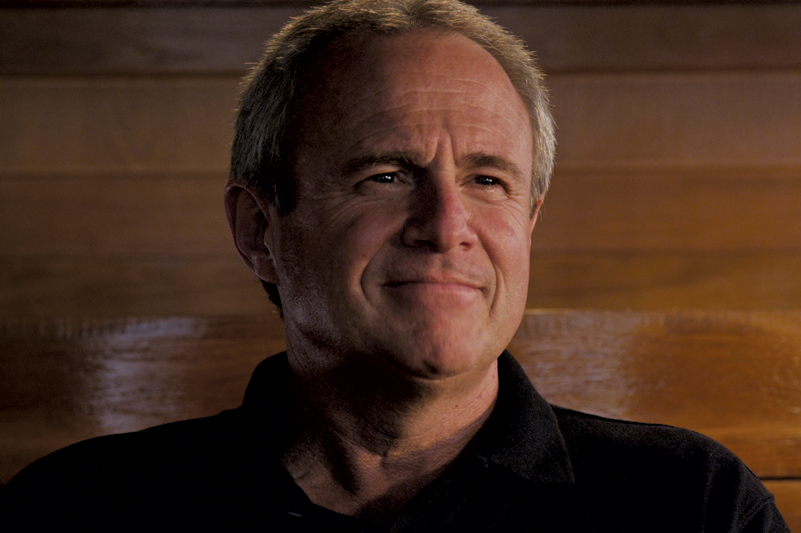

It’s bad enough—though increasingly common, given our nation’s historically and globally unprecedented enthusiasm for incarceration—to end up behind bars for something you did. But to spend a quarter-century behind bars for supposedly bludgeoning your wife to death when you were actually at work, having nothing to do with the awful crime, is another thing altogether. And to have your only son, still a preschooler, taken from your arms and raised to believe that you killed his mother is a punishment that defies description. But having beaten the stacked odds that once landed him in prison, and having conquered a fresh set that got him back out again, Michael Morton seems unfazed by simple description.

By Michael Morton

Simon & Schuster

304 pages; $25 Simon & Schuster

Austin’s least fortunate son, Morton endured 25 years in prison before DNA proved his innocence and identified his wife’s real killer. Evidence that would have solved the horrific murder—and ultimately might have saved the life of another woman later targeted by Mark Norwood—had been first ignored and later hidden by police and prosecutors in Williamson County. It wasn’t just a simple case of bad luck or evidence falling between the cracks; the same tactics used to investigate and prosecute Morton’s case were well-documented conviction-seeking strategies in the office of former Williamson County District Attorney Ken Anderson and assistant DA John Bradley, who took over when Anderson was elevated to the position of district judge.

The truth ultimately set Morton free in 2011, but there’s no recovering 25 lost years, and Morton’s new memoir, Getting Life, carries the extra potency of its non-fiction status. Only the real world could be so cruel and ironic, unfurling so improbable and yet effortless a plot. Morton’s skillfully plainspoken delivery makes the unfathomable all too real as he chaperones us into the strange waters of the courtroom and the depths of prison life. His prose gains power through precise description, aided by the voluminous journals in which he recorded his ordeal.

Through it all, somehow, Morton seems to have retained a remarkable sense of wonder that’s vital in explaining the book’s inevitable question: how a man in Morton’s shoes managed to maintain his humanity, let alone nurture forgiveness, through so many years of unearned captivity. That’s not to say he emerged unscathed. Even before the agonizing years in prison, standing alone on the night of the murder in the bloody scene that his bedroom had become, he recognized, “It is not enough to say that this was hard for me, not enough to say that standing there and taking in this carnage was heartbreaking. I almost felt as if seeing this, trying to process this terrible scene, was changing me, right down to my bones, altering me in ways that would never—could never—be reversed.”

Wouldn’t it be nice if Morton were an anomaly? It is a natural, almost unconscious urge to want to distinguish ourselves from the unlucky, to seek some distinction that might separate us from the fate to which another has succumbed. But Morton was as average as they come, an everyman who honeymooned at Disney World, worked in a grocery store, and lived in a new Austin suburb with his wife, Christine, and 3-year-old son. Middle-class and white, with no criminal record, he doesn’t fit the typecast for the penitentiary-bound. More to the point, of course, he was utterly innocent, and not a shred of physical evidence supported Morton’s guilt at trial. Caught in a web spun from circumstantial evidence and brazen lies, Morton is the most dreaded of wrongful-conviction specimens, proof that it could happen to anyone.

Evidence of the brokenness of our legal system abounds, and Morton is just an especially revealing case study in a national chronicle of injustice. To date, 1,419 innocent Americans have been exonerated after serving a combined total of nearly 13,350 years behind bars, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, a joint project of Northwestern University and University of Michigan law schools. That number includes 317 exonerees who, like Morton, were cleared by DNA evidence. But the unparalleled power of DNA evidence is available in only a fraction of cases. The Innocence Project, the national nonprofit organization that pioneered wrongful conviction investigations and helped free Morton, closes more than a quarter of its cases because key evidence has been lost or destroyed.

Other prisoners, unlike Morton, aren’t even afforded the relative luxury of languishing behind bars. They are executed, begging for justice with their final, haunting words. The ghastly experience and everyday risk of executing the innocent—Texas’ ongoing struggle to reconcile the case of Cameron Todd Willingham is only one example—raise the stakes even higher. Confronted with the reality of a system of justice that has wrongly eclipsed the lives of Morton and so many other innocent Americans, it’s impossible not to look over one’s own shoulder and wonder, what if?

What we can see is not reassuring. In Morton’s case, police ignored tangible evidence pointing to the real killer because it didn’t comport with the theory they’d hatched. And while ineptitude is one thing, the unabashed arrogance, dishonesty and outright contempt for legal fairness that is demonstrated by Morton prosecutor Anderson and so many of his brethren is worse. Misconduct by officials led to wrongful convictions in nearly 60 percent of homicide cases where an innocent person was later exonerated, according to the National Registry for Exoneration’s conservative estimate.

Wouldn’t it be nice if Morton were an anomaly? It is a natural, almost unconscious urge to want to distinguish ourselves from the unlucky, but Morton was as average as they come.

During the inquiry that brought Anderson’s wrongdoing to light, Morton said it was “the grace of God” that helped him keep bitterness and hunger for revenge at bay during his long incarceration. Asked by the judge what he hoped the probe would accomplish, he gave an answer that’s heartrending in its simplicity. “I felt my face redden and my eyes fill with tears. I couldn’t control it. This meant a great deal to me. I very much wanted this process to be fair. I didn’t want any more pain for anyone—I simply wanted our lopsided practice of criminal justice to reach a better balance. I didn’t want anyone else to go through what I had—and I knew firsthand that there were other people behind bars who, like me, didn’t belong there. I looked straight at Judge Sturns and spoke directly to him. ‘I ask that you do what needs to be done, but at the same time—to be gentle with Judge Anderson.’ Ken Anderson didn’t even look up.”

There is no triumph in a story like this, only shreds of hope. By now we all know that life and the American justice system aren’t fair, but we keep striving toward some semblance of equity nonetheless. Morton wished and waited and worked relentlessly, and then one day received his just desserts. May we all.

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.