What You Need to Know About the SB 4 Legal Battle

The first major hearing on the “sanctuary cities” ban is set for next Monday in San Antonio.

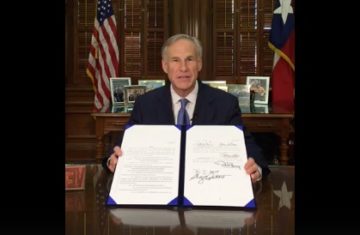

On the night that Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed Senate Bill 4 into law, Luis Roberto Vera didn’t sleep. Instead, the 61-year-old civil rights attorney holed up in his San Antonio office, working on a lawsuit. “I went all night, all day, didn’t take a bath, nothin’,” he said.

The next day, on May 8, Vera filed the first legal challenge to SB 4 on behalf of El Cenizo — a tiny border town with the oldest “sanctuary” ordinance in the state. Since then, a flurry of legal challenges has emerged from other cities and counties, setting up a battle that will play out over the hot Texas summer and beyond.

By way of reminder, SB 4 is Abbott’s crackdown on “sanctuary cities,” a term that broadly refers to communities who choose not to prioritize deporting undocumented immigrants. Set to go into effect September 1, the law will ban any policy that limits cooperation with federal immigration agents, and threatens to fine or jail elected officials who run afoul of its provisions.

The law will also allow police to question the immigration status of anyone being detained — not just arrested — thanks to what’s called the “show me your papers” provision.

In 2011 and 2015, moderate Republicans helped kill similar bills, but 2017 was no year for moderation, leaving immigrants and advocates with the courts as their last, best hope. Below is what you should know about the key players, legal arguments and timeline involved in one of the state’s biggest legal battles.

Who is suing whom?

El Cenizo, San Antonio, Austin, Dallas and El Paso County have all taken legal action against SB 4, and Houston has announced it may soon join. Of Texas’ major cities, only GOP-leaning Fort Worth has stayed out of the fight.

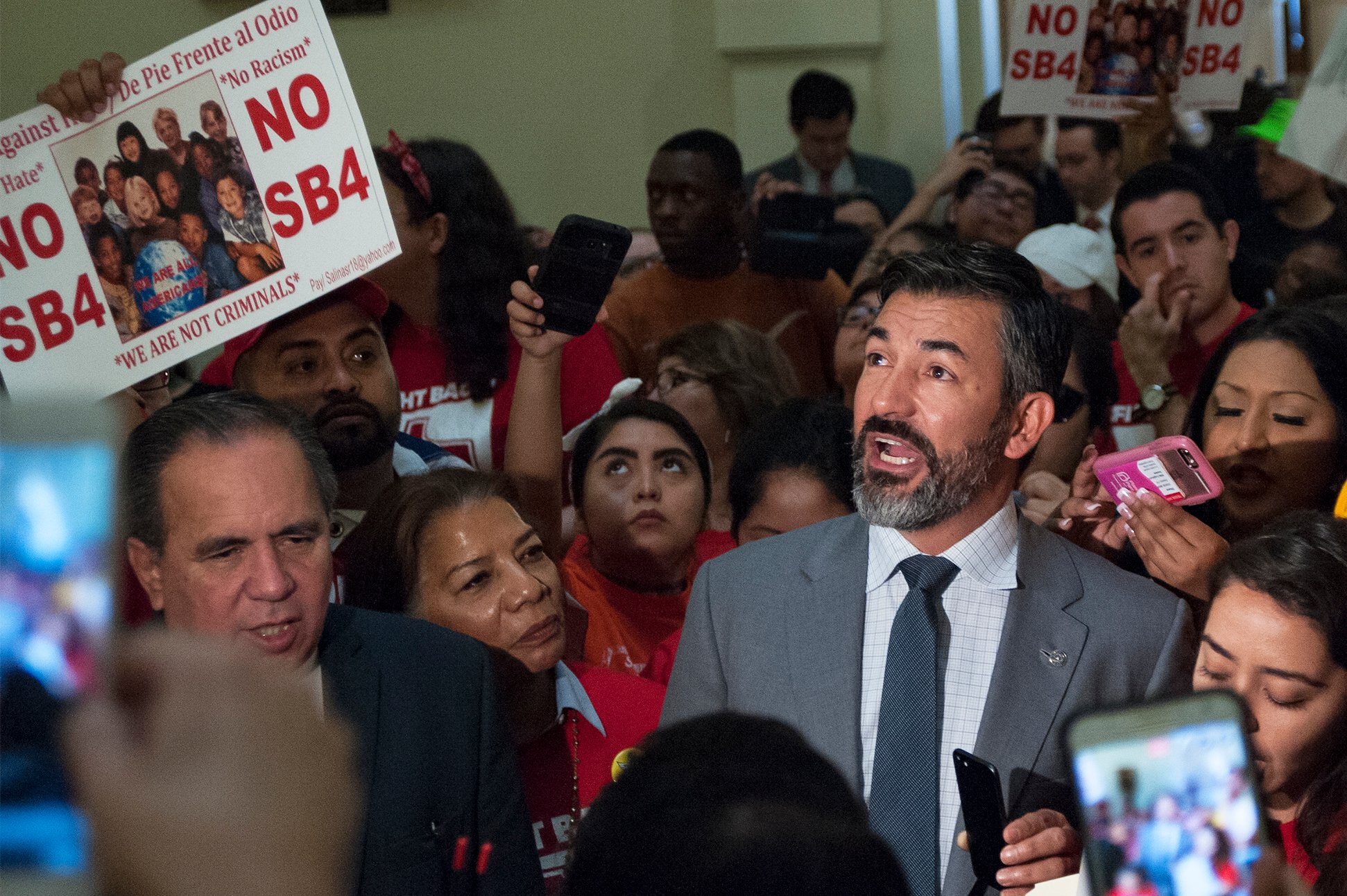

The growing list represents a “continued showdown between the state government, governed primarily by a right-wing Republican regime, and the progressive majority growing in Texas cities,” said Austin City Councilman Greg Casar.

On May 7, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed a pre-emptive lawsuit in Austin’s federal court to try to get ahead of the legal challenges and have the law declared constitutional.

“Everyone was surprised by the pre-emptive suit,” said Thomas Saenz, president and general counsel of MALDEF, “because most responsible lawyers don’t engage in that kind of shenanigans — and that’s what it is when you file a frivolous suit without standing.”

Motions have been filed to dismiss the attorney general’s suit, which sits before U.S. District Judge Sam Sparks. A Paxton spokesperson told the Observer the agency “does not comment on ongoing litigation.”

So there are a bunch of different lawsuits?

Initially, yes, but the lawsuits against SB 4 have been consolidated and are set to be heard in San Antonio by U.S. District Judge Orlando Garcia.

Representing the cities are a bevy of heavyweight civil rights organizations, including the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), the Texas Civil Rights Project (TCRP) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

The ACLU is bringing in attorneys who beat Trump’s “Muslim ban” back in January.

What’s the timeline here?

The first important hearing is set for June 26 in San Antonio. Garcia plans to hear a motion for an injunction. The plaintiffs are requesting that he block the law from going into effect while the underlying case plays out. The law is set to take effect on September 1.

Paxton has other plans. He filed a motion to transfer the case to the Austin court where he filed his SB 4 suit. “We are pretty confident [Garcia] won’t transfer,” said Marisa Bono, an attorney with MALDEF. “The state hasn’t shown a legitimate reason for transferring.”

Paxton is also set to get a hearing on “all pending matters” pertaining to his preemptive suit, in Austin, on June 29.

Multiple attorneys told the Observer the case will likely end up at the U.S. Supreme Court, and that could take years.

“If you look at the history of how Paxton’s office litigates these cases … there’s no middle ground for them,” said Jose Garza, an El Paso attorney who also works on the voter ID and redistricting cases. “They’re not interested in reaching compromises.”

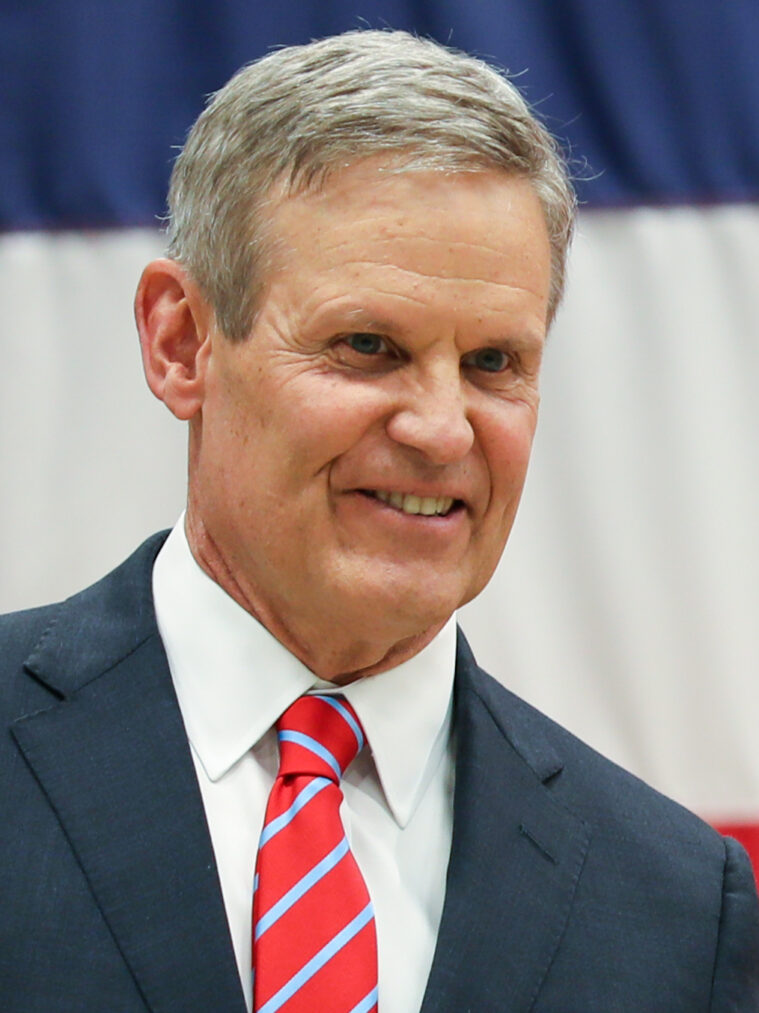

What do we know about Judge Garcia?

Garcia is the chief justice of the Western District of Texas and a 1994 Clinton appointee. In 2014, he overturned Texas’ ban on same-sex marriage.

Most relevant to the SB 4 case, he ruled this month that the Bexar County Jail violated a Mexican man’s constitutional rights when it held him on behalf of immigration authorities for two and a half months after his criminal charges were dismissed.

What exactly does the lawsuit say about the constitutionality of SB 4?

The suit alleges a broad range of violations, but the most crucial arguments hinge on the First, Fourth and 14th amendments, as well as the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause.

The suit claims SB 4 violates the First Amendment rights of elected and appointed officials by threatening to punish them if they “endorse” any policy that limits local enforcement of immigration laws. “Government cannot tell you what to say or not to say based on the content of what you’re saying, which is exactly what SB 4 does,” said Efrén Olivares, an attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project.

City council members or police chiefs could even be jailed for their speech, which Olivares called “the kind of thing you hear about in dictatorships.”

SB 4 will also require jails to comply with all immigration detainers, which attorneys say will run afoul of the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable seizure. Detainers are requests from the feds to local jails to hold someone beyond when they would normally be released so immigration agents can potentially deport them.

Garcia’s Bexar County ruling questioned the constitutionality of those requests.

Detainers are sometimes issued in error, and have even been placed on U.S. citizens. Olivares, the attorney, explained: “Some ICE detainers are based on criminal probable cause, and some are not … SB 4 makes them all mandatory, and therefore it will lead to unconstitutional detention.”

The suit also alleges, like hundreds who testified against the bill in the Legislature, that SB 4 is racially discriminatory. In legal terms, that means it violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

The suit argues the law will disproportionately impact Hispanic Texans, whom police will profile as potential undocumented immigrants. The law’s “show me your papers” provision ensures that brown-skinned or Spanish-speaking Texans can be asked about their immigration status even during routine traffic stops, the suit states.

SB 4 joins a long list of Texas legislation challenged as intentional racial discrimination.

Finally, the suit argues that SB 4 treads on the authority of the federal government, violating the Supremacy Clause. Because immigration is strictly the feds’ domain, states cannot change or create their own immigration laws, the suit argues. For example, states cannot make optional immigration detainers mandatory.

“There are certain things that states can do related to immigration,” Olivares said. “For example, in Texas, you cannot get a driver’s license if you’re undocumented. … Courts have said that’s fine. But, for example, a state could not say people are going to be deported if they drive 30 miles above the speed limit. That wouldn’t fly, because it’s interfering in the immigration laws.”

The Supremacy Clause was key in striking down provisions of Arizona’s infamous SB 1070.

Will things GOP lawmakers said and did be held against them?

Yes, very much so. The lawsuit liberally draws on the legislative debate over SB 4 to build the case that the bill was passed with discriminatory intent, drawing on evidence such as GOP lawmakers calling immigrants “illegals,” “terrorists” and “drug runners.”

The suit contains a blow-by-blow description of the May 29 incident when Representative Matt Rinaldi, R-Irving, called federal immigration agents on protesters at the Capitol. The suit claims Rinaldi “assum[ed] that all of the members in the gallery were undocumented because they appeared to be ‘Latino.’”

What will this all cost, and who’s footing the bill?

“The state of Texas has shown it has an open checkbook — a never-ending source of taxpayer money to defend unconstitutional laws,” said Garza, the El Paso attorney.

The civil rights groups will have to spend a lot as well, he said, but if they win, Texas will be liable for the attorney’s fees.

Has the law reinvigorated Texas’ movement for immigrant rights?

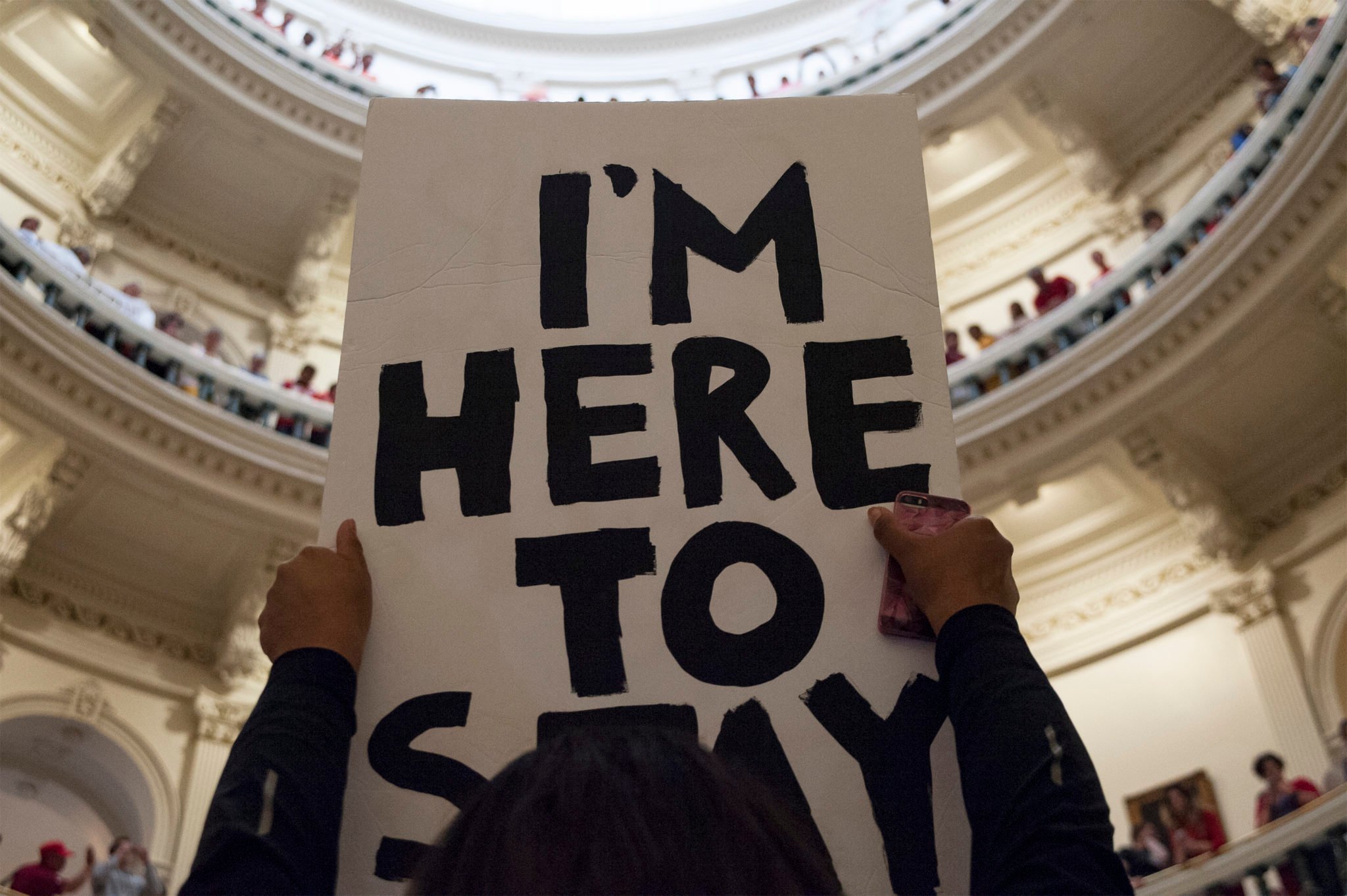

It has. In the bill’s earliest stages, hundreds turned out to the Capitol to testify, dragging committee hearings late into the night. When the bill reached the House floor, Democratic lawmakers spent 16 emotional hours trying to blunt its impact.

As the bill sat on the Governor’s desk, 24 people were arrested for occupying his office in a push for him to veto it. And after he signed, protesters responded with a week of gatherings, culminating in a hundreds-strong Mother’s day march through downtown Austin.

One Saturday night, a crowd blared mariachi music outside the Governor’s mansion at 3 a.m., and on the Legislature’s final day, more than 1,000 protesters disrupted the Texas house, filling the Capitol’s every floor. Organizers have said the protests will continue as part of a “summer of resistance.”