New Data, New Questions on Sexual Violence as a Texas Public Health Issue

There’s this thing that happens when your journalism beat often includes reporting on sexual violence: People start to tell you their personal stories of experiencing harassment or assault. The prevalence of sexual violence and its effect on survivors becomes unavoidable. Your family, friends, colleagues — even people you only know from social media — share difficult details about their lives. You sit through jury selections for sexual assault cases and you watch potential jurors have to raise their hands when the prosecutor asks, “Who’s been the victim of, or knows a victim of, sexual assault?” People send you links to all kinds of terrible stories. All day. Every day.

In short, I never don’t know about the prevalence and impact of sexual assault.

But then a new study comes out, and the subject of sexual violence churns once again through the news cycle. Those stories that people have told you, the stories you can’t not know, are stripped down to their bare bones, the details made quantifiable and digestible in numbers and percentages.

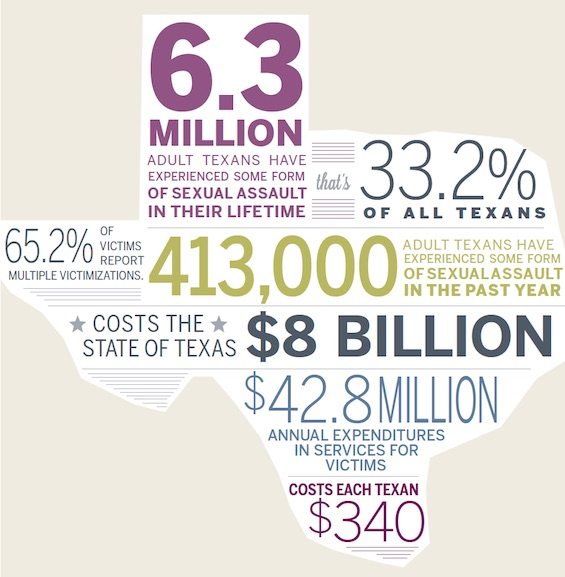

Now it’s happened again, with two new sets of data recently made available on sexual assault in Texas. In August, UT-Austin researchers released “Health and Well-Being: Texas Statewide Sexual Assault Prevalence Study” (TSSAPS), which estimates that 6.3 million adult Texans — just over 33 percent of us — have experienced some form of sexual assault. According to the study, more than 400,000 Texans were victimized in the last year alone.

And on Monday, the Association of American Universities (AAU) released a study about the prevalence of sexual assault on college campuses, including UT-Austin and Texas A&M University. Researchers found that nearly 12 percent of students surveyed at 27 universities reported experiencing “non-consensual penetration or sexual touching,” with “transgender, genderqueer, non-conforming, questioning” students (classified as a group in the study as “TGNQ”) experiencing sexual assault most often.

At UT-Austin, 23 percent of TGNQ undergrad students and 18 percent of undergrad women reported experiencing sexual violence, while 15 percent both of women and of TGNQ students reported being victims of sexual violence at Texas A&M.

This new data doesn’t tell me much that we didn’t already know — that millions of Texans, including many thousands of college students, have experienced sexual violence — but I was impressed to see researchers using a couple of new approaches in their conclusions.

It’s no small relief to see a large mainstream study say that sexual violence is a major health issue, shifting the problem of sexual assault from individual burden to state responsibility.

For example, researchers with TSSAPS found that sexual assault victims in Texas were much more likely to have “physical, mental, and emotional problems that limit activities” than non-victims — 41 percent versus 27 percent. Certain medical conditions are more common for victims than non-victims, including asthma, frequent headaches and chronic pain. A little over half of all victims said they experienced psychological or emotional distress following the assault, with women over twice as likely to say so compared to men.

But here’s the big intervention: TSSAPS researchers concluded that the public should understand sexual violence as “a major health issue for Texas women” and that the “suffering of men and boys should not be minimized or ignored.”

It’s no small relief to see a large mainstream study say that sexual violence is a major health issue, shifting the problem of sexual assault from individual burden to state responsibility. From this, we can start asking more comprehensive questions, ones that finally go beyond simple discussions about whether victims reported, or when. We can ask, instead: What is the state doing to prevent sexual violence and support survivors?

In another important turn, both studies used a broad definition of sexual violence. TSSAPS tailored their questions to reflect crimes described by the 2014 Texas Penal Code, asking respondents about unwanted behaviors like “made you have vaginal sex” or “put their fingers or any object in your vagina or anus,” but also included questions about whether a perpetrator of violence had “exposed their body parts to you,” “[wore] you down by repeatedly asking for sex, or showing they were unhappy,” or “pressured you by telling you lies,” among others. For the AAU survey, people were asked about non-consensual penetration but also unwanted sexual touching, like kissing or groping.

These expanded definitions are incredibly important not only because they actually mirror Texas law, but because they show just how many ways consent can be violated. Rape, on its own, is far from the totality of sexual violence, and in order to understand the ubiquity of this violence and its effect on Texans, we need to be much more expansive in how we talk about it.

The AAU survey also gives us insight into a particular group of students whose experiences with sexual violence are often ignored: LGBTQ students. At UT-Austin, Texas A&M and nationally, students who identified as transgender, genderqueer or non-conforming, questioning or who chose not to list any gender designation, reported higher rates of sexual violence. They also had bleaker expectations when it came to getting support from other students or their university, the possibility of retaliation for reporting sexual violence, or how well their schools deal with problems of campus sexual violence.

And for all groups of victims, sexual assault is a chronically underreported crime for which prosecutions are rare in comparison to the crime’s prevalence. This is as true in Texas as anywhere else. TSSAPS found that less than 10 percent of victims said they reported their assaults to law enforcement. The AAU survey found that the vast majority of UT-Austin and Texas A&M students who experienced sexual violence never reported it to officials, though most did tell a friend. There was a much lower chance that a person would report if they were incapacitated during their assault as opposed to being physically forced — though researchers also tracked data about a smaller set of students (1.7 percent) who reported being both incapacitated and physically forced.

Participants in both surveys gave a range of reasons for why they did not go to the police or university officials: not believing that there was a crime to report, being too young or too scared or too ashamed, fearing they wouldn’t be believed, or worrying that reporting could jeopardize their immigration status.

When I read these reports, I thought of the survivors I’ve talked to about their experiences and their fears, and about how hard it is for many of them to admit even to themselves what happened. How can they trust that anyone else is going to believe them, or even that they can trust another person at all? I can’t help but see their faces and hear their voices, thinking over and over again that these studies are about actual people — our friends, family members, neighbors, colleagues — who face this violence or the threat of it all the time.

While there is a certain kind of joy in having official studies that validate what too many of us already know, and some comfort in the knowledge that a whole new group of people who were once ignorant before may no longer be, there is an accompanying frustration: How can something that seems so urgent, ubiquitous, and important in my own life be such surprising news to others? It is good and hard all at once.

And so I wait for the next story, the next link, the next survivor who reaches out to tell me their story, and I go back to work.