No News is Bad News

As more and more rural Texas communities become “news deserts," the civic life of small towns is suffering too.

For the last eight years, Cochran County, a square of farming and ranching country in the High Plains, has gone without a local newspaper. The weekly Morton Tribune printed its last issue in 2011, putting the county of 2,900 people on a growing list of “news deserts” — communities without a single local source of news.

“We’ve gone so long without [a newspaper], I guess we’re just used to it now,” said Kim Silhan, the mayor of Morton, the county seat.

People now rely on word of mouth for news, gathering in the senior citizen center to keep up with happenings or calling City Hall for information about social activities such as the community fall fest. But without a paper regularly covering city and county government, the farming and ranching industry, or even the champion six-man Morton football team, civic life is impoverished. Silhan attributes declining voter turnout to the Tribune’s closure.

“They don’t realize we’re having an election,” she said. “People just don’t interact and pay attention as much without a paper. And not that everybody bought a paper, but at least it was there.”

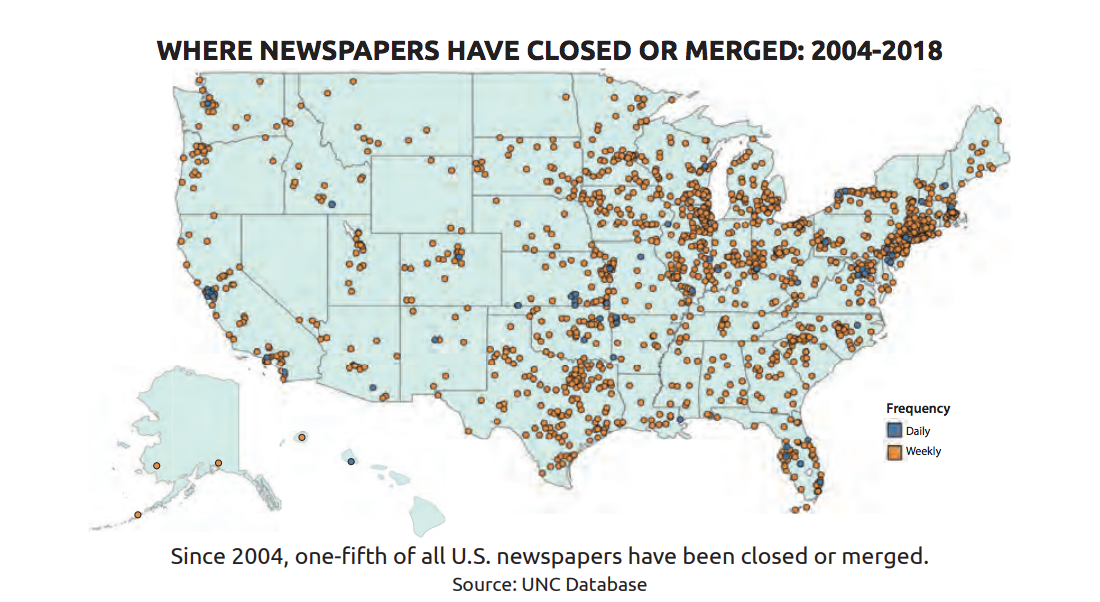

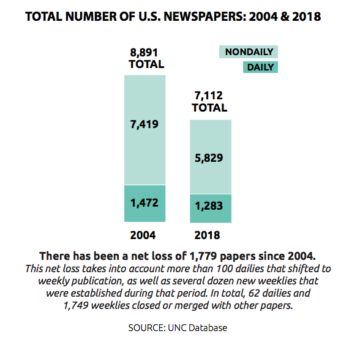

Morton is among more than 1,300 communities across the country considered a news desert, according to an October report by University of North Carolina researchers. The UNC scholars found that 146 weekly newspapers and 14 dailies have closed in Texas since 2004 — half of them in rural areas. Many of the remaining small daily and weekly newspapers are shells of their former selves, providing little in the way of public service journalism.

Across the country, news deserts have cropped up in both cities and small towns. Rural areas are particularly vulnerable because small local papers are typically independently owned, often by families or individuals. Rural papers in such small markets are unattractive to outsiders, and owners are pressured to close if they face declining profits or can’t find a buyer.

The shuttering of the Morton Tribune, which resident Sherrill Sahlin owned, caught many by surprise. Stephen Henry, publisher of the Levelland and Hockley County News-Press, said an owner before Sahlin had approached him about buying the paper, but they couldn’t close the deal. Like others in the area, Henry said he wasn’t sure why the Tribune closed, but he offered a guess.

“Why does any newspaper fail? Because of lack of support of the community or mismanagement or a combination of both,” he said. “The Morton Trib had at least four owners in less than a decade.” Henry said his paper has tried to cover Cochran County news as best they can.

“They don’t realize we’re having an election. People just don’t interact and pay attention as much without a paper.”

Meanwhile, the corporate owners of newspapers in metro areas are struggling to fill in the gaps. In May, the San Antonio Express-News laid off 14 reporters, the largest cut since 2009 when 75 reporters were laid off.

“The big papers can’t afford to send people to [South and West Texas], and the little papers are fading away,” said John MacCormack, a reporter for the Express-News. “We used to mobilize for anything, anywhere. At the drop of a hat, we would drive 400 miles to cover a story. But now, we don’t have too many people; we don’t have the money. … A lot of things go uncovered.”

For people in Morton and the other small towns in Cochran County, the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal is the nearest big-city paper, but its reporters rarely make the hourlong drive to cover county commissioners court hearings or other day-to-day news. Silhan said reporters for the Levelland and Hockley County News-Press occasionally go to Morton City Council meetings if something major is happening.

There’s a cost to the dearth of coverage. A 2018 study found that “the loss of government monitoring resulting from a [newspaper] closure is associated” with more expensive government employees, higher taxes and bigger deficits. That’s not to mention any criminal acts or abuses of power that may go unreported.

But even rural areas with a newspaper often lack experienced reporters to fill the watchdog role.

“A lot of communities are getting less, or even no, what I would call professional news coverage,” MacCormack said.

That seems to be the situation in Duval County, a ranching community of 11,200 people in South Texas. In the late ’90s, Alfredo Cardenas sold the twice-a-week Duval County Picture, which later became the weekly Duval Enterprise. The current owner relies heavily on unpaid citizen-journalists to provide coverage of school board and city council meetings. Cardenas says the quality has suffered as a result.

“The volunteers are not necessarily journalists. They’re community people who want a newspaper to continue … they do it more as a social thing,” Cardenas said.

Enterprise publisher Poncho Hernandez defended the volunteer system. “We use volunteers because any newspaper that doesn’t use volunteers is missing a big segment of the population. They’re not tailoring to everybody’s needs,” Hernandez said. “As a publisher, I recognize the importance of putting together stories that are local in nature and if they’re put together by the local community, the better.”

Natalie Stroud, who directs the University of Texas at Austin’s Center for Media Engagement, said journalism’s financial woes escalated about a decade ago, when advertisers realized they could target local audiences more easily through Facebook or Google. Consequently, news organizations have had to scale back coverage and lay off staff to make ends meet.

“In the long term, something will take place because of how critical news and information are for our democracy,” Stroud said. “But in the short term, things are in a period of tremendous transition for this industry.”

Though digital news outlets have filled some of the space left behind by collapsing newspapers, they’re overwhelmingly concentrated in major urban areas. And digital outlets can’t fend off problems associated with the loss of local news, such as increased political polarization. A November study published in the Journal of Communication found that after a newspaper closes, readers consume more national news, which exposes people to intense political messages and increases polarized voting.

“We use volunteers because any newspaper that doesn’t use volunteers is missing a big segment of the population.”

Gale Huckaby, a librarian in Leakey, the county seat of Real County on the southwestern fringe of the Hill Country, remembers not so long ago when newsstands with the local paper and other publications were available throughout town. Then the county’s weekly Hill Country Herald was only available at the library and gas stations. And as of December, the Herald isn’t available anywhere — its last edition was printed in December. (The owner, Julie Becker, declined to explain why she was shutting down.)

Huckaby said the loss is deeply felt in the community. “A lot of our community is older folks,” she said. “And they don’t go on Facebook and they don’t read websites, so they really don’t know what’s going on in town except through the paper. The newspaper is what they count on to give them information.”

Real County Sheriff Nathan Johnson has seen the closing of a paper play out before. While he was chief of police in Winters, Texas, the local publication merged with the paper in neighboring Brownwood.

“In small communities, your school district is the heart of your community. Everybody wants to know that,” Johnson said. “Are they going to make it to state? How’d the basketball game turn out? … They like to see pictures of their kids, of people they know.” For now, Huckaby and Johnson are holding out hope that someone will open up another local paper.

“The misnomer is that the big cities — their newspapers are dying all over the country because people are going to social media and doing everything online,” Johnson said. “But for small communities, a lot of people say, ‘Oh, the local paper will never dry up. It’ll always be here.’ But that’s not true either.”