Observing the Borderlands

As the Texas Observer’s border reporter from 2008 to 2018, Melissa del Bosque investigated corruption and uncovered injustices.

A version of this story ran in the July / August 2024 issue.

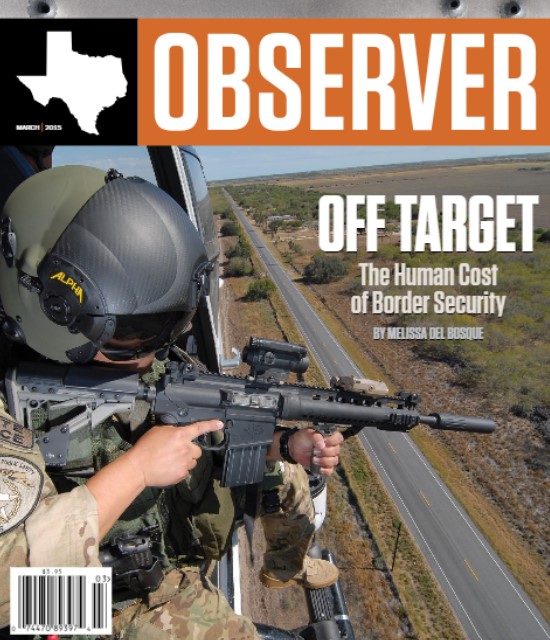

After stints at the McAllen Monitor and as a Lege staffer, Melissa del Bosque worked at the Texas Observer as a staff writer from 2008 to 2018, chronicling life in border communities, investigating the government’s militarization of the region, and telling migrants’ stories. Along the way, she produced some of Texas’ most influential border reporting, including the Hillman Prize-winning “Death on Sevenmile Road,” an exposé of how state police shot at a truck from a helicopter, killing migrants riding in the bed.

Her 2014 four-part series on migrant death in South Texas for the Observer and the Guardian, “Beyond the Border,” won an Emmy and a National Magazine Award. She is the author of Bloodlines: The True Story of a Drug Cartel, the FBI, and the Battle for a Horse-Racing Dynasty, a 2017 book based on her reporting on Zetas cartel money laundering.

Del Bosque, now based in Tucson, Arizona, co-leads The Border Chronicle, a newsletter featuring analysis and on-the-ground reporting about the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, and she also serves as investigative editor for Lighthouse Reports.

TO: How did you become a border reporter?

I grew up in San Diego [California], so I grew up at the border. I was always fascinated by the culture and endlessly intrigued by the fact that you can be standing in one country, looking into another country. We’re there, side by side.

I was at a crossroads in deciding what I wanted to do with my life. I had already been through a creative writing program and I needed to make a living, so I was going to go into journalism, and I really wanted to focus on border journalism. There were border bureaus, and border journalism was actually a thing because of [the North American Free Trade Agreement] being passed [in 1992].

But by the time I became a border journalist, it wasn’t really a thing anymore. It’s more, you’re an immigration reporter—whereas I’ve always seen the border position as incorporating other things like the environment and politics. It’s this amazing beat because it’s local and it’s international.

What drew you to the Texas Observer?

I crossed over to the dark side and started working in politics. I was working for Chuy Hinojosa, the [state] senator from McAllen. I was up there in the Capitol doing environment and health communications. The things that I was seeing happening inside—the legislative process and how the sausage gets made—were awful and mortifying. This is not a reflection on Senator Hinojosa, because he was great, but the process was corrupted by money and influence.

I would always call the Observer, because I knew them. This is when Jake Bernstein was the editor, Dave Mann was there, and Nate Blakeslee was still writing for the Observer. I would call them, totally indignant and enraged by what was happening that week in the Capitol, and I’d be like, “You guys need to get over here and write about this.”

I think they got so tired of me calling that they said, “Well, why don’t you just come and work here?” I took like a $10,000 pay cut and went back to journalism.

What themes have been a constant in the two decades that you’ve reported on the border, and what’s changed?

I always look at it from the perspective of the person who’s most affected by the targeting, surveillance, and violence. We hear so much from Washington, D.C., and from politicians about how they think the border is insecure. I’m really most interested in how that impacts people in everyday life. What is it like to cross the border in the back of a truck, under a tarp, and then have state police shooting at you from a helicopter? We don’t hear enough of that perspective. It’s not reported on enough, and there are more and more people being impacted and targeted by so-called “border security,” by the surveillance, and the armed people, and the surges.

I listen to The Border Chronicle podcast, and a theme that I’ve heard in several episodes is how what happens at the physical border affects people far beyond the border. Can you talk about that?

I’ve always thought of the border as being the testing ground for the rest of the nation. License plate readers, sensors, and drones are tested at the border—and then they’re rolled out into the interior. We need to pay close attention to what’s happening at the border, because it’s the future. Increasingly, with border externalization—which is sort of like U.S. imperial policy—[the border] gets pushed out into countries all around the world. We have Border Patrol agents who are traveling around the world and training border guards in techniques that they use. There’s surveillance, there’s detention, and all these things that are taught to other countries who are implementing U.S.-centric border restrictions and trying to prevent people from moving north. It’s really a global policy now.

What were the most consequential stories to you, or your favorite stories that you reported on, at the Observer?

I think Sevenmile Road. That was a really important story because it was so outrageous. First, that [the Texas Department of Public Safety] would think it’s a good idea to train snipers to shoot from helicopters, and shoot out the tires of cars while they’re in pursuit. Then, of course, they didn’t tell local officials that they were doing this, but they did debut it on a cable show. Then when the shooting occurred, they completely blocked any media outlets from getting the video from the helicopter, from getting any of the documents from the investigation, so that we could really decipher what had happened exactly and how these people had died.

In probably one of the luckiest strokes in my career, I filed a public information request with Hidalgo County, and the district attorney blocked me. But, in the shuffle between the outgoing and the incoming DAs, they forgot to respond to my public information request within the acceptable number of days. I benefited from the dysfunction. They were forced to hand over all the information that they had presented to the grand jury, which had no-billed it. I was able to get the video and all of those documents that way.

What, to you, is the Observer‘s legacy?

The Observer goes after stories that no other outlet in Texas does. I don’t think the Observer is afraid of anything or anybody. They’re not into insider access. They’re not beholden to anyone, and that really gives them the superpower of being able to go after any entity or person, no matter how big they are—which is something that’s so important, that we need more of.

This interview, which is part of the Observer’s 70th anniversary coverage, has been edited for length and clarity. Support for our 70th anniversary interview series has been provided by KOOP Radio in Austin, which permitted its studios to be used for recordings.