Will Georgetown’s ‘Old South Ball’ Rise Again?

On Saturday, about 100 people, some donning their finest Confederate army uniforms and antebellum hoop skirts, gathered to dance the Virginia Reel and sip Chatham Artillery Punch inside the Williamson County courthouse in Georgetown.

Outside, the crowd was the same size, but the mood was notably chillier. Protesters walked the perimeter of the courthouse square holding signs reading “History Not Hatred,” and “Do you know the history you are celebrating?” One man used a bullhorn to address guests as they arrived, demanding: “How many slaves would you own if you could?”

No one responded.

The event inside — dubbed “The Old South Ball: A Civil War Dance” and organized by the Williamson County Museum — provoked harsh criticism from residents who contend that it amounts to a slaver’s party, celebrating white privilege. The event has forced folks in this area to confront the kinds of questions that are becoming more and more common amid a growing national conversation about racial oppression and the legacy of slavery.

Whose history is being remembered, and whose is being erased, when we romanticize the Confederacy, give Confederate memorials pride of place in public spaces, or teach our children to minimize the role of slavery in the Civil War?

And after the dance is over, what happens next?

Ideologically, Georgetown is light years away from liberal Austin, but geographically, it’s just 20 miles up I-35. In the mid-19th century, Williamson County was dotted with cotton fields — fields worked by enslaved black men, women and children. About 900 enslaved people lived in the county in 1860. Today, about 7 percent of Williamson County’s almost half a million residents are black.

The county courthouse, a restored Beaux-Arts building, anchors Georgetown’s idyllic town square. The week before the ball, I met the director of the county museum and the ball’s mastermind, Mickie Ross, there, next to what used to be a segregated water fountain. Ross, who is married to the town’s mayor, Dale Ross, was wary of the press.

“We’re not glorifying slavery. The ball is not about slavery, it’s about experiencing a historical time period.”

But Ross told me that people shouldn’t be offended. “We’re not glorifying slavery. The ball is not about slavery, it’s about experiencing a historical time period.”

I asked Ross if she could see how the ball could be viewed as exclusionary. “No one is being excluded,” she said. “I’m as horrified as anybody else by slavery. My family were poor whites, we didn’t own slaves.”

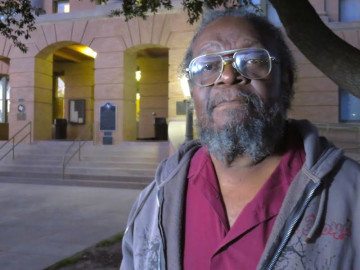

Williamson County resident Eddie Hurst, who is black, said he’s so familiar with these kinds of defenses that he can predict them even before they happen. Hurst ran unsuccessfully for county commissioner in 2014.

“They want to say the Civil War wasn’t about slavery,” Hurst said. “They say that was a long time ago and my ancestors didn’t own slaves. This time period doesn’t represent anything good for blacks.”

Several ball attendees I spoke with seemed oblivious to the point. “No one would say slavery is a good thing,” said John Hairgrove, dressed in a Confederate army vest and accompanied by his 11-year-old daughter. “I’m just here so my little girl can dress up and have a good time.”

During my conversation with Ross, her phone rang. Someone wanted to buy a ticket to the ball. Ross told the caller she was sorry, the event was sold out, but she would put his name on a waitlist.

“I’ve been getting supportive calls like that all the time,” she said, hanging up the phone. “Donations have been pouring in since this thing started.”

Ross told me she initially envisioned the event early last year, but it only became a target of opposition last December when a few “rabble rousers started the controversy.”

That “rabble rousing” involved Georgetown residents like Sherwin Kahn, who drafted a petition asking Ross and the museum board to reconsider the ball. The party, he wrote, “sends the wrong message to the community and the world in times that are still troubled by racial strife and violence.” More than 275 people signed on.

Ross wasn’t dissuaded. Instead, she compared to a living history exhibit. “History is part of who we are. We should remember it and teach it,” she said.

At the protest, I asked Kenneth Witherspoon, who is black and has lived in the county since 1992, if he agreed with Ross’ reasoning.

The event wasn’t teaching historical reality, he said, but rather “whitewashing” history. “This commemorates a culture based on slavery. People like me weren’t welcomed at an event like this.”

An hour and a half after the ball began, while the revelers inside the courthouse were still reeling, and the last few straggling protesters were leaving the town square, I caught up with Rachael Jonrowe, a Georgetown City Council member.

Jonrowe played a central role in the controversy earlier this month when she suggested that city grant money awarded to the museum not be used to fund the ball. (The museum subsequently declined the funds.)

She said that in the wake of the murders, last summer, of nine black church-goers in Charleston by a white supremacist, the ball is “tone-deaf.” But she also thought the public controversy may have a silver lining.

“It has forced some people to look at things they don’t want to look at,” she said. “We are still dealing with old biases, with the legacy of slavery, and it’s good to talk about it.”

I asked the council member about the likelihood of a second annual Old South Ball.

“Slim to none,” she responded — she didn’t think residents would stand for it next year. But while the ball may have sparked some conversations, the criticism didn’t end up changing everyone’s mind.

Would Mickie Ross do it all over again, still throw the party even after the protests and petitions?

She said she did have one regret.

“I’ll say this, the choice of the name was a poor choice,” she said. “I’ll admit that.”

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.