On Giant’s Shoulders: New Cinema History Dissects Texas Tropes

"Giant" was meant to confront certain ugly implications about Texas, chiefly that it is perpetually big, bigoted and booming.

In 1956, America was ascendant, and Texas was America. Eleven years after the end of World War II, the greasy machinery of capitalism had conquered the country and modern America was being churned out on its assembly lines. Glistening cars were rolling onto endless new highways, Hollywood’s company-town factories were sculpting new models of celebrity and Americans were enshrining their newfound prosperity by connecting that wealth to their own myths of self-made grandeur. All the while, many others were looking on, wondering how those myths would apply to them, and watching as McCarthyism, civil rights and sexual politics all clawed from beneath the bucolic façade of a rising world power.

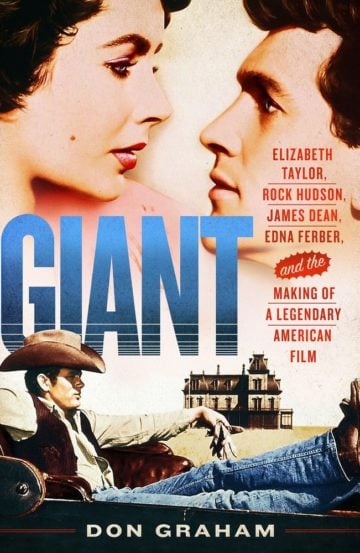

By Don Graham

St. Martin’s Press

$27.99; 336 pages

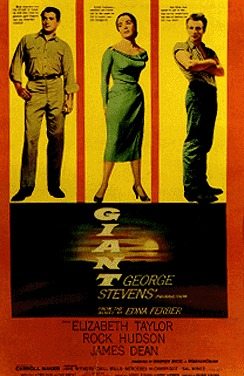

That same year, Giant, the three-hour cinematic epic of generational change and ambition on a vast Texas ranch, was released to much fanfare. A story of old money and new, Giant follows a massive Texas ranch from the time cattle was king to the reign of oil (symbolized in the film by a literal rain of crude). It questions conservative Texas tradition — and racism — along with the excesses of a recently invented economic actor: the Texas oil millionaire. This is a story that’s long been a part of our state identity, and now beloved author and University of Texas English professor Don Graham has given us a new book to make sense of it all. In the fascinating but tediously titled Giant: Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, James Dean, Edna Ferber, and the Making of a Legendary American Film, Graham plots out a stampeding tale of personal and professional triumph and heartache, one not unlike the story in the film it chronicles.

There may be no better person to revisit the film’s meta-narrative than Graham, who has spent much of his career studying Texas, tilting at the windmills of history, myth, narrative, of South and West, town and country. As the inheritor of “Life and Literature of the Southwest,” the storied UT English class taught for many years by J. Frank Dobie — a man so steeped in Texana that he himself is now a kind of state symbol — Graham has for decades flogged the work of the lesser-known Katherine Ann Porters and Américo Paredeses of the world, as well as the requisite O. Henrys and Walter Prescott Webbs.

Graham’s Giant is breezy but thoughtful. The book is sometimes biographic, by turns solid history writing, and often a considered examination of Texas in the popular imagination and the images that went on to define 20th-century Texas. If the film’s oil and cattle barons, flinty dames and suits with boots were all spliced together into a person, the result would surely resemble The Simpsons’ “Rich Texan” stock character.

Graham plots out a stampeding tale of personal and professional triumph and heartache, one not unlike the story in the film it chronicles.

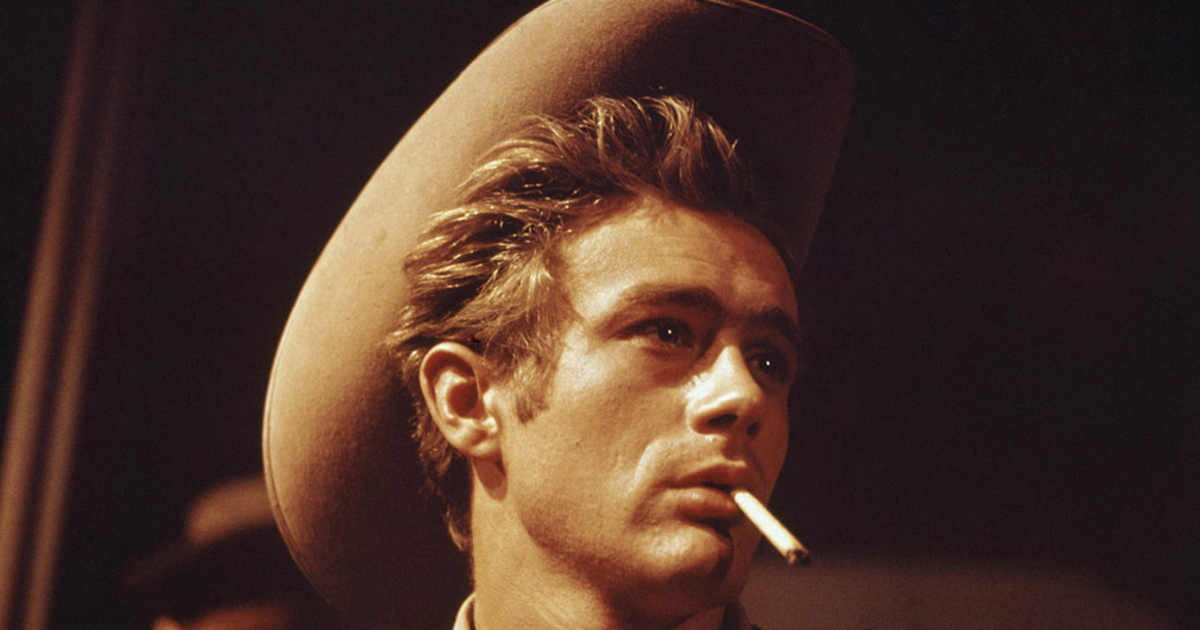

Graham establishes his characters in natural, personal ways, never pulling toward celebrity gossip, but instead throttling the story at breakneck speed into complex character study, just as “Jimmy” Dean throttled his Porsche down the Sunset Strip. A good portion of the early chapters build up the set dressing for the legendary shoot and its aftermath, like so much brown-and-tan clapboard on an endless prairie. A reader who knows little about Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor or James Dean won’t get lost by the time the cameras are rolling in Marfa, where Giant was filmed. Rock Hudson, he of teddy-bear eyes and barrel chest, is a fairly vacuous but hard-working greenhorn, often tongue-tied and ever-jealous of Dean. Taylor is a mercurial recovering child star, well on her way through a string of calamitous marriages. Dean is, well, James Dean, part cornfed farm boy, part neurotic hipster, completely at the whims of his own boiling cauldron of emotions and alternatively sweet and sour, gay, straight, or bisexual. Edna Ferber, who wrote the novel the film was based on and helped write the screenplay, is an erudite Texas-hater, a classist with an interest in civil rights, a major theme of both the book and film. It was an ambitious undertaking that caught its makers at just the right time, it seems. As Graham writes, “They were nothing as much as wildcatters setting forth to drill for oil in the fabled wilds of West Texas.”

One of the joys of reading Graham is his ability to tell a complete tale, a scene from life, and cap it with a laconic statement of a theme. And while it does give a fairly complete blow-by-blow of the production process, the book is principally a history, meaning Graham is not afraid to tell the reader how we got to Giant, and how it still inspires.

“Six decades later,” Graham writes in the final chapter, “Giant still has the power to surprise. Critics approach it like an archeological dig.”

Besides the people whose names are included in the subtitle, director George Stevens is a major player and a vital lens to understanding the film. Stevens served in the Army Signal Corps in the war, and was shaken to his core by the horrors of Dachau. He meant for his film to take a major stand about segregation in particular. The book deftly interweaves the narratives of race in the film and in real-life Texas, quoting signs in San Antonio restaurants that read “We Serve Whites Only. No Spanish or Mexicans.” Graham wryly adds his coda: “One wonders how many Spaniards passed through San Antonio in any given year.”

The examination of modern American anxieties is worth the read for anyone today, while the book’s high school cafeteria-level drama keeps it all moving, speeding ever faster until, like James Dean, it cedes control to history. The whole enchilada is well-summarized by an anonymous previewer who saw an early cut of the film back in ’56: “This film is wonderfully done—” they write, “but its implication of America (Texas, if you like) is bad publicity for our country.” The Texans depicted in Giant, which Ferber based on the story of the real-life King Ranch, are blinded by greed and brimming with intolerance. The film felt accusatory exactly because it was meant to confront certain ugly implications about Texas, chiefly that it is perpetually big, bigoted and booming.

As one of our state’s respected writers, Don Graham joyfully dissects those implications and their sources. It’s a riveting, quick read, but one that feels — for lack of a better word — giant.