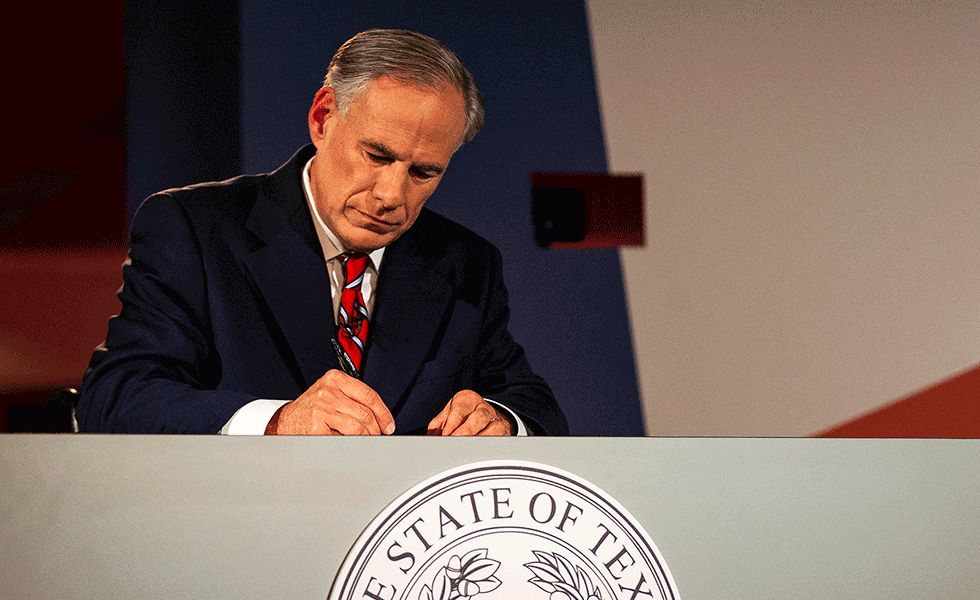

On Rodney Reed Case, Greg Abbott Gets a Political Reprieve

A last-minute court intervention relieved political pressure on the Texas governor, who was ultimately able to keep his capital punishment bona fides intact.

As Rodney Reed’s November 20 execution date drew closer, all eyes turned to Governor Greg Abbott.

When new evidence surfaced casting doubt on Reed’s conviction for the 1996 rape and murder that put him on death row, it quickly drew national—and even international—attention. Dr. Phil featured the case on his show. Oprah Winfrey, Beyoncé Knowles Carter, and Kim Kardashian called on the governor to stop or delay Reed’s execution in light of the new information. Even Senator Ted Cruz stepped up as part of a large bipartisan coalition of Texas lawmakers asking Abbott to grant a reprieve.

For weeks, Abbott had faced mounting public pressure to stay Reed’s execution, at least long enough to look at the new evidence. Ten days before his execution date, hundreds of people protested outside the governor’s mansion in downtown Austin.

“I heard Governor Abbott is a good man. Well, I say actions speak louder than words,” Reed’s mother, Sandra, said at the rally. “Show me and the world just how good of a man you are. Take into consideration all of what you know, all of what you’ve seen. There are others that were before you that didn’t live up to their oath. Will you?”

Meanwhile, Abbott seemed more preoccupied with waging his war on Austin’s homeless population and the city’s liberal leaders. Time was quickly running out for Reed.

Then, everything changed. On Friday, the Texas Board of Pardons and Parole—a seven-person panel of gubernatorial appointees—issued a unanimous recommendation to Abbott that he grant a 120-day stay of Reed’s execution. It was an unexpected development. “It’s exceedingly rare for that board to recommend anything resembling relief for a person facing imminent execution in Texas,” said Kristin Houlè, executive director of the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty.

It wasn’t clear if Abbott would act on the recommendation, and we never got to find out. Within hours, the Texas Criminal Court of Appeals rendered it moot by referring the case back to trial court to examine the new evidence and reconsider key components of the case, including Reed’s innocence.

At that point, Abbott finally broke his silence, tweeting: “For those sending messages about Rodney Reed please note that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals halted Rodney Reed’s execution and sent his case back to the trial court for further review.”

You could almost hear the sigh of relief.

Abbott has forged his career as a law and order devotee in a state where the politics of the death penalty were ossified, even boasted of. As Texas attorney general, he aggressively pursued death penalty convictions on behalf of the state. In 2011, he ruled that a state forensic panel couldn’t look at old evidence in the case of Cameron Todd Willingham, who was eventually executed for setting fire to his home and killing his children. The arson science that helped convict Willingham has since been debunked, and many believe that Abbott’s decision allowed for the death of an innocent man. During his five years in the governor’s office, Abbott has presided over 50 executions and granted only one commutation. In the wake of the El Paso and Midland-Odessa mass shootings, Abbott posited that “expedited executions” of convicted mass shooters would be a “nice addition” to the state’s legislative response.

“It pretty much takes him off the hook. He doesn’t have to decide anything, he doesn’t have to act. Whatever the court decides, he can pretty much wash his hands of the case.”

Since the death penalty was reinstated in 1982, Texas governors—Democrat and Republican—have overwhelmingly affirmed its use. Today, death sentences and executions have become less common. George W. Bush and Rick Perry presided over almost twice as many executions a year as Abbott during their tenures. But Texas, led by Abbott, is still at the forefront of capital punishment: Last year, the state was responsible for more than half the nation’s executions.

“[Governors] perceive it as being something that the public wants and they’re not going to stand in the way of the public’s wish,” said Kenneth Williams, a former death penalty lawyer and law professor at the South Texas College of Law. “Even when there’s questions about a person’s innocence.”

Texans’ appetite for the death penalty remains, though it is waning. In 2010, 78 percent of Texans supported the death penalty; as of 2018, 65 percent of Texans still did.

There are efforts to rein in the state’s capital punishment laws. A trio of death penalty reform bills passed out of the state House in 2019 but died in the Senate, once again saving Abbott from having to enter the fray.

But the Reed case brought newfound levels of publicity to the Texas death penalty and put an unprecedented amount of political pressure on Abbott. The high criminal court’s last-minute decision to reopen the case served as a convenient release valve.

“It pretty much takes him off the hook,” Williams said. “He doesn’t have to decide anything, he doesn’t have to act. Whatever the court decides, he can pretty much wash his hands of the case. Mr. Reed gets another chance in court and if the court says, ‘We’re not convinced he’s innocent,’ Mr. Abbott will be able to point to that. And if he’s exonerated, Abbott will be able to say, ‘Well, this is evidence that [the system] works.’”

Meanwhile, Texans are left wondering what the governor may have done. Would he have followed the recommendations of his pardon board and granted a reprieve, or would he have let the clock run out on Reed, quite possibly killing another innocent man?

That uncertainty is unsettling, to say the least.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Texas Congressional Candidate Shannon Hutcheson Defended Corporations Against the Vulnerable. EMILY’s List Endorsed Her Anyway: Shannon Hutcheson has billed herself as a fierce reproductive rights advocate. But the corporate lawyer has papered over a troubling record, including her defense of a prison guard who sexually abused migrant women.

-

Driving My Life Away: As physicians leave small towns, rural Texans must travel farther and farther for health care.

-

‘You Can Only Take So Much’: Low-Income Hurricane Harvey Survivors Sue Over ‘Discriminatory’ Recovery Process: The lawsuit accuses state and federal officials of favoring wealthier, white homeowners over poorer black and Hispanic renters.