On the Border, a Struggle over Water

As the Rio Grande runs dry, Texas and Mexico fight for a diminishing resource.

Drought is different along the border. Unlike Central Texas, which worries over its aquifers and its lakes, or East Texas, which jealously guards its mammoth reservoirs from booming cities, or the Panhandle, which is draining the Ogallala Aquifer, the border depends on a desert river that divides two nations.

South Texas has come to rely on the Rio Grande, but the river is drying up. Global climate change and prolonged drought, coupled with Mexico’s failure to deliver the water it’s supposed to under an international treaty, have taken a toll on the region’s water supply.

In a state that ranks third in total agricultural and livestock production in the nation, Texas farmers are worried. Crops may survive one year of scarce rainfall, but extended drought renders fields barren. Moreover, reduced snowpack in Colorado and New Mexico—which scientists link to climate change—means less water enters the Rio Grande upstream.

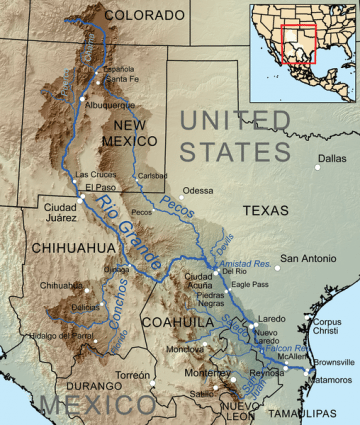

More than ever, the replenishing waters of Mexico’s Rio Conchos are crucial to reviving the Rio Grande and to saving farmers in the Rio Grande Valley. Texas politicians have taken to publicly denouncing Mexico and urging the U.S. government to force Mexico to deliver the water it’s supposed to.

But the situation is more complicated than Texas leaders let on. In all their finger pointing, officials leave out two important points: Mexico is not yet in violation of the treaty, and it may not have much water to spare. Mexican farmers and ranchers are losing crops and livestock fast, and Mexican cities may soon see reduced water allotments. The problem may not be Mexican intransigence, as Texas officials contend, so much as depleted water supplies in an increasingly arid region.

Under a 1944 water treaty, the U.S. is entitled to one-third of the Rio Conchos, which joins the Rio Grande near Presidio, Texas. Mexico is supposed to release an average of 350,000 acre-feet of water into the Rio Grande each year over a five-year period for use by Texas. The treaty suggests—but doesn’t explicitly mandate—a release of 350,000 acre-feet every year. Mexico simply must release a five-year total that averages out to 350,000 acre-feet a year. Texas officials claim that Mexico typically relies on downpours and hurricanes to “bail it out” of meeting its yearly average. Any time the international reservoirs fill up, Mexico is exempt from making deliveries and a new cycle begins. But currently, both Falcon Lake and Amistad Reservoir are less than a quarter full; Amistad, the larger reservoir, hit its record low in late April and continues to drop, so Mexico should be releasing water, at least that’s how desperate farmers on the U.S. side see it.

Many Valley farmers are on the verge of losing their irrigation water, and they say the situation could get worse if Mexico follows through on plans to build dams on the Rio Conchos.

“Not only have they not given us any information that they plan on delivering this water … but they’re making plans to divert even more water, which could further complicate things,” Rep. Eddie Lucio III (D-Harlingen) told a legislative committee in March. “The Rio Grande river is our water lifeline down there.” But there is little state lawmakers can do other than bug the feds for help.

Texas officials, including Gov. Rick Perry, have admonished the U.S. Department of State for not doing enough to ensure treaty compliance. The State Department hands down foreign policy guidelines to the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC), the bi-national body charged with enforcing treaties.

“IBWC and the State Department have achieved—nothing. Their efforts seem to be limited to a shrug of the shoulders and claims that ‘there’s nothing we can do,’” reads a recent editorial by Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Commissioner Carlos Rubinstein and Texas Agriculture Commissioner Todd Staples.

But as some experts point out, the treaty requires Mexico to make deliveries in five-year cycles. So as long as it pays up by 2015, Mexico is technically not violating the treaty.

“Texans seem to be aggressive in castigating Mexico for not meeting its treaty obligations when in fact they still are,” says Ronald Kaiser, who chairs the water program at Texas A&M University. “I think the wisdom of the folks who negotiated the treaty is to recognize that we have periods of drought and that it’s really impractical for every year to say [Mexico has] to give us this amount of water because that amount may not be available.”

Mexico may not be in violation yet, but it has been before. In the late 1990s, the U.S. accused Mexico of hoarding water after it failed to pay up for nearly 10 years. Farmers grew indignant when then-Agriculture Commissioner Susan Combs toured the Valley with satellite photos showing swaths of green on the other side of the border.

Many South Texas farmers have had their land declared completely unproductive, or “zeroed out,” by insurance companies. Dale Murden, who owns a 20,000-acre farm in Monte Alto, says at least 30 percent of his land has been zeroed out. The insurance companies are still evaluating damage, so that number could increase.

Murden says he wasn’t around for the record drought in the 1950s, but this is the worst year he’s seen. “I’ve already laid off six of my employees, and I’m trying to hold it at that,” Murden says. “You just have to cut back to bare bones and hang on for next year and hope that it rains.”

Dr. Luis Ribera, an agricultural economist with Texas A&M’s AgriLife Extension Service, predicts agricultural losses in South Texas will reach $100 million this year. That number is double the region’s losses in 2006, when extended drought emaciated crops.

Murden says this season’s losses will be far greater than those in 2011, when the drought hit its peak, but farmers could still draw water from reservoirs.

The irrigation district that serves Murden’s farm limited farmers to one irrigation period per year. He used that water for his main crops, sugarcane and grapefruit—two South Texas staples—but had to sacrifice cotton and grain, which are his next most profitable crops.

Water scarcity is creeping up on Valley cities as well. The cities rely on a large amount of irrigation water to push their water down the channel. Without the pushwater, the cities can’t get their water. In March, irrigation districts started notifying farmers they’d be cut off in 60 days—when that happens, city governments will have to start buying extra pushwater to keep the taps flowing.

Rio Hondo, Raymondville and San Benito have already started looking for other sources of municipal water. Rio Hondo Mayor Alonzo Garza told a local newspaper that paying for pushwater would bankrupt his 2,443-person town. Nearby San Benito is evaluating its options, none of which are cheap, Assistant City Manager Hector Jalomo told the Observer. San Benito is considering drilling a well at its water treatment plant, but doesn’t have the hundreds of thousands of dollars required for the project and has already started applying for financial assistance.

Under the 1944 treaty, either of the two countries can be exempted from water deliveries for one year in case of “extraordinary” drought, and the current dispute partly involves just how bad the drought is on the Mexican side.

Andrea Morrow, spokesperson for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, contends Mexico’s portion of the Rio Grande basin hasn’t experienced “exceptional” drought since May of last year. “Mexico could have and should have delivered much more than they have,” she says.

But that view isn’t universally shared. Kaiser says the climate conditions that exist in Texas inevitably extend to the Mexican border states. “To say [that] west of the Rio Grande they have no drought and everything east of the Rio Grande, we’re all in drought—that’s not hydrologic nor climatological reality,” Kaiser says. “Climate just doesn’t stop at a political border.”

North American Drought Monitor maps from February through April 2013 show areas of extreme and exceptional drought in Texas spilling just over the border into the Rio Grande basin in Mexico, but these dry spots are much smaller than the ones covering Texas. It’s worth noting that most large Mexican reservoirs in the Rio Grande basin are at dire levels. The National Farm Workers’ Confederation (CNC) reports that more than 50 percent of the country is in drought, particularly Chihuahua and Coahuila. The ground is too dry to sustain crops, and livestock producers have seen many of their cows miscarry from lack of healthy pastures, according to articles in the Mexican press. Cayetano Dominguez of the Confederation’s Coahuila branch told the Observer the state has lost 60 percent of its livestock.

“Some of that is because the animals died and some of that is because they had to be sold off,” Dominguez says. “There just wasn’t enough food for them.”

Dominguez says most of the state’s farmers can produce only enough to feed themselves and are no longer selling crops. It’s now cheaper to buy maize from other countries than to produce it in parts of Mexico, he says.

But even when Mexico has more water, U.S. officials argue the country treats its obligations to the U.S. as an afterthought. Mexico doesn’t regard the United States as a “user,” says Sally Spener of the International Boundary and Water Commission, and instead allocates water to all its users before considering its treaty obligations.

The U.S., on the other hand, sets aside Mexico’s water before determining American allocations, Spener says. In exchange for the water Mexico sends, the U.S. has to release 1.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water to Mexico each year and deliver another 60,000 acre-feet out of Elephant Butte Reservoir in New Mexico to the Juarez Valley.

Spener’s counterpart on the Mexican side of the international water commission, Jesus Luevano, says Mexico isn’t obligated to deliver water by certain times because while U.S. deliveries are tied to a calendar, Mexican ones are not. The tradeoff is Mexico goes into “debt” if it doesn’t deliver by the end of the cycle, while the United States doesn’t. Last year, the U.S. delivered only 20 percent of the water it’s supposed to give the Juarez Valley out of Elephant Butte. On four occasions in the past 10 years, it has delivered only about half of what it should—but the U.S. never has to make up that amount to Mexico.

The Elephant Butte obligation pales in comparison to the water the U.S. promises Mexico out of the Colorado River and—as officials repeatedly point out—the U.S. has never failed to make those deliveries.

Stakeholders on the U.S. side of the border point to Mexico’s plans to build 15 dams on the Rio Conchos as the latest example of its disregard for Texans. Nine of those dams would be in the Rio Grande basin, but most of the projects are small, ranging from 80 to 8,000 acre-feet capacity. (By comparison, Lake Travis in Austin has a capacity of more than one million acre-feet. Amistad reservoir on the border can hold up to 3.28 million acre-feet of water.)

One new reservoir would be 49,000 acre-feet and the largest would be at Ojinaga (across the border from Presidio, where the Rio Conchos joins the Rio Grande) with a capacity of 243,000 acre-feet. Luevano says the dam would be used for flood control and could aid in making deliveries to the United States. Spener says the U.S. hasn’t been given enough information to determine its potential impact.

But Texas farmers aren’t so reserved. “That’s one or two [dams] too many,” Murden says. “If you’re me.”

The solution, Murden says, lies in the State Department’s intervention. It’s a sentiment echoed by water officials and state politicians, who are convinced that federal government involvement will be the key to solving the water dispute.

But Kaiser says periods where both countries don’t have enough water will likely become the norm, and that conservation is vital to preventing future conflicts. Others have suggested making temporary changes to the treaty that can require specific water releases.

For now, Mexico’s deliveries continue to be a trickle compared to the heavy flow the Valley needs. Politicians and farmers complain that the Luis L. Leon Reservoir on the Rio Conchos has been above capacity for months. Since May 1, releases from Luis Leon have totaled more than 16,000 acre-feet, but the reservoir, less than a quarter the size of Lake Travis, is still at 106 percent capacity. Luevano says Mexico’s federal water authority, CONAGUA, plans to release more water so that the reservoir is at capacity or just below it. Multiple emails and calls to CONAGUA seeking comment weren’t returned.

The May releases kept Mexico from falling further behind in water deliveries but did nothing to ease the anger in Texas. The Rio Grande reservoirs remain dangerously low. If Mexico makes a significant delivery in June or July, it will be too late for some crops, but Murden says it could save sugarcane and citrus in the Valley.

And if not? “Then I’ll have to start worrying about how to keep trees alive,” he says. “My citrus and the sugarcane will start to die and that will be devastating. To lose the sugar industry in the Valley would be a real hard thing for me to come back from.”