On the Road With Beto: Is O’Rourke’s Personality-Driven Campaign Reaching the Right Voters?

On the Road With Beto: Is O’Rourke’s Personality-Driven Campaign Reaching the Right Voters?

The next several months will be an experiment at break-neck speed to see if O’Rourke can overcome low name recognition and build a rapport with non-white voters.

–

On a warm Sunday this Spring, Stephanie Corté, an organizer with the Beto O’Rourke campaign, stands on one side of a picnic table in a park in Rio Grande City. On the other side are Michelle Mendoza and Oscar Gonzales, the two people who’ve responded to the campaign’s call to learn how to volunteer for O’Rourke. Just a month before, the El Paso congressman had locked down the Democratic nomination to take on Ted Cruz for the U.S. Senate, beating two underfunded and little-known candidates.

But here in Starr County, O’Rourke barely limped past 30 percent of the vote. He lost much of South Texas to one of those underfunded, little-known opponents, Sema Hernandez, and took a little better than half of the vote in many of the state’s largest urban counties. The poor showing suggested that O’Rourke had work to do to reach the party’s traditional base voters, in the places where they live. Even in the best of times, the Rio Grande Valley is a challenge for statewide Democratic candidates: The area is overwhelmingly Democratic but it has some of the lowest voter turnout in the entire country.

To beat Cruz, O’Rourke will need a lot of help here, and for that he will be leaning on an army of volunteers, spread across the state and organized by a central digital hive mind, in the style of the Bernie Sanders campaign. It’s called distributed field organizing, and it’s a big part of the campaign’s plan for the fall.

That’s where Corté, dressed in black Converse and a smart suit, fits in. Corté went to the University of Texas-Pan American in Edinburg, moved to Washington, D.C., to work on Sanders’ Senate finance committee staff and then returned to the Valley this year to serve as O’Rourke’s South Texas field organizer.

At the pavilion, Mendoza and Gonzales are eager to get to work. Mendoza says she became an O’Rourke convert after attending a town hall in Edinburg, and offers to help organize phone banks. Gonzales found O’Rourke through Facebook, and offers to host events at the coffee shop he owns in town. The idea is that the two of them will help recruit other volunteers, who will in turn find other volunteers, and that will create a network in town on the campaign’s behalf.

Corté asks if the two have questions. Mendoza’s hand shoots up. “Is there any way that Beto could come to Starr County?” The candidate has been through the Valley multiple times, but hasn’t spent much time here. Corté says she’s told the campaign he needs to. Mendoza says her neighbors don’t know who he is, and that they need to see O’Rourke’s face. “When I tell people about Beto they’re like yeah, OK, great, but who is he?” she says. “When I met him at that town hall meeting, that solidified my vote.”

Corté agrees — there’s a lot of work to be done in connecting people here to the campaign. “Name recognition is very important,” she says. “We’re trying to get the name Beto out there. Beto, Beto. Because during the primary, he was neck and neck with Hernandez.” The dominant theory of O’Rourke’s poor performance in the primary is that voters who didn’t know him voted instead for the Latina candidate. “When I talk to Spanish speakers, they say Orourque? Orourque? They don’t understand what I’m saying. I say, just think Beto, Beto, he’s great, he’ll fight for you.”

It would be wrong to make too much of one volunteer meeting — many have been well-attended and energetic — but the back-and-forth that night points to some key issues facing O’Rourke’s campaign, which is counting to an unusual degree on the strength of the candidate’s presence and charisma. Ted Cruz needs only to turn out white voters to win, while Democrats have to mobilize and persuade many different communities, across a large and complex state. And they need to do all that with much less money and infrastructure — not to mention the psychological barrier of a 24-year losing streak.

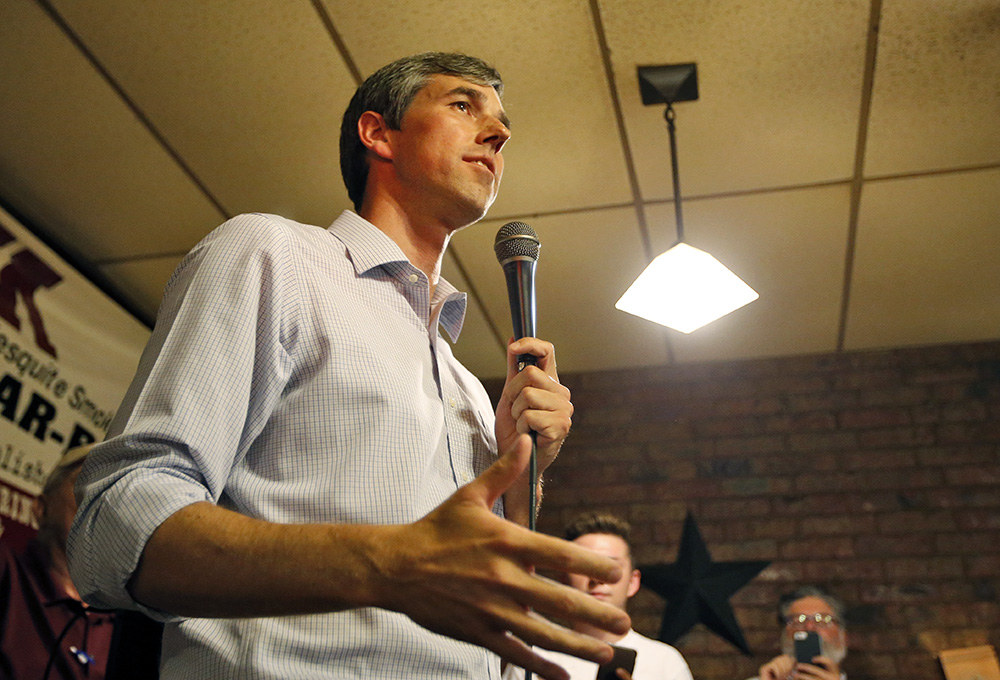

O’Rourke’s bet was that his campaign could partially circumvent those problems, short-circuit them, with the power of Beto O’Rourke — his charisma and charm, and his ability to gin up free media. When I interviewed him last summer, O’Rourke told me he had found himself “allergic” to the pitch he had gotten from the political consulting class, about the “traditional” way to run a campaign in Texas. He set out to do it his own way — and he’s come a long way. He’s raised a tremendous amount of money, and generated a highly unusual level of excitement, at least among the state and national media and among the class of Texans that makes up his strongest base of support — particularly, suburban, urban, and young progressives.

But we’re entering the home stretch — early voting starts in just four months. How is O’Rourke doing in overcoming those hurdles? In the spring, I went on the road to catch up with the campaign. There’s still a lot of cautious optimism from observers — or at least, as much optimism as you can get from a Texas Democrat — but some disquiet, too, about O’Rourke’s campaign strategy.

Their doubt, which is partially supported by results from recent polls and the March primary, is that O’Rourke has been slow to build name recognition and a rapport with non-white voters, the bedrock of the Democratic Party. The next several months will be an experiment at break-neck speed, to see if O’Rourke can overcome those weaknesses. And an experiment too, to see: How much is a good candidate worth?

–

O’Rourke clearly loves the road, and thrills at the excitement Democrats in small towns feel at his presence: “I know you thought it would be a cold day in you-know-where before I could get Democrats to show up in Glasscock County,” population 1,226, says the local Democratic Party chair when he introduced O’Rourke in March.

But it also brings him to to some strange places. In late April, for example, O’Rourke held a 7 a.m. “breakfast town hall” at a Sonic Drive-In in the desolate West Texas town of Ozona, population 3,225, before holding four more events in even smaller cities, ending in Leakey, population 425. The traditional rule of a campaign is to go where the voters are.

In private, veterans of state Democratic politics express concern about the limits of O’Rourke’s unorthodox approach, but few are willing to speak on the record. An exception is J.D. Gins, who helped run Barack Obama’s Texas effort in 2008 and Bill White’s campaign for governor in 2010. Later, he served as executive director of the Travis County Democratic Party, where he became a leading internal critic. But in 2015 he quit politics to open a brewery in Taylor, leaving him free to talk publicly in a way most other Democrats I spoke to for this piece were not.

Was O’Rourke’s poor primary performance in South Texas simply a product of low name recognition and his opponent’s last name? Gins has another theory: “I wouldn’t be surprised if some of it was the politiqueras sending a message,” he said.

A lot of Democratic politics in Texas is built around formal or informal machines, and the politiqueras run the machine in the Valley. They extract a tax from Democratic campaigns, and then produce votes. Most campaigns pay the tax. “We were shaken down in a meaningful way,” Gins said of Bill White’s gubernatorial campaign. “The decision was made that it needed to be done.” O’Rourke’s non-traditional campaign, so far, hasn’t played along. Gins’ theory is that the bad performance in the Valley on primary night, in part, might be a message — you need us.

In the next few months, O’Rourke will face a similar problem in other parts of the state, where the traditional ways of doing politics clash with a tech- and volunteer-driven grassroots campaign. The people who walk blocks in October in neighborhoods of Dallas or Houston, for example, “still expect to get paid,” Gins said. They treat it like a job, a serious one, whereas if volunteers don’t show, or they embarrass the campaign, you’re out of luck. O’Rourke’s campaign will have to decide how much they want to do it the old way, and how much they want to do it their way.

“When I tell people about Beto they’re like yeah, OK, great, but who is he?”

There’s also a risk to not cultivating community leaders, who don’t expect money but do expect to be consulted. “There are definitely folks who are the traditional gatekeepers, the churches and community leaders,” Gins said. “And if those people aren’t fired up for you, it’s hard to mobilize people.” The campaign will either have to yield to the gatekeepers or go around them.

At one event in February, a man told O’Rourke he was concerned about the AFL-CIO’s decision to withhold an endorsement of the candidate, after O’Rourke declined an invitation to appear at the union’s convention in January. (They endorsed him a few weeks later.) O’Rourke tells the man, in a candid moment, that he “loves” the AFL-CIO, but that the union was trying to buy his loyalty.

“There is some heartburn over the fact that I don’t take PAC money,” O’Rourke said. He explained that AFL-CIO leadership told him, “if you don’t take our PAC check, people are gonna believe that you’re not working for us.” That kind of thinking, he said, was “sick.”

“I’m gonna work for you because it’s the right thing to do. I’m not going to fight for you because I took a $10,000 check.” It’s an answer the audience appreciated. But the unions are a big part of the Democratic coalition in Texas, and a consultant-driven campaign would make sure to show them respect.

“Part of the challenge that the O’Rourke campaign is having right now,” said Gins, is that “they don’t have a lot of people on their team that know how to do the infrastructure building.”

Campaign vets can tell a candidate that “this person always asks you for $1,000 a day and they can always get you into the Sunday churches you need, and this person always gives you bullshit. There’s a reason that consultants are helpful, and it doesn’t mean you have to listen to them on everything. Consultants are just people who’ve worked on lots of campaigns.”

O’Rourke, for his part, agrees that the campaign has a lot of work to do. “I think we’ve got to do more and a better job, in really every community,” he told me. By way of example, he said, “we were in Laredo a couple months ago. We had a big block-walk, organized by our Polis block-walking system. This young man who was one of the volunteers said, ‘Hey, I don’t see Mr. Lozano’s name on here.’ I was like, ‘Who’s Mr. Lozano?’ He’s like, ‘Oh, Mr. Lozano is the mero mero. He’s the guy in this neighborhood. I can’t believe you’re not talking to him. Here, I’m going to take you.’”

That turned out to be a good idea. “Not only does he run an auto repair shop, so everyone in the neighborhood is getting their car fixed there, but they had four or five kids, so Mrs. Lozano knew every mom in the neighborhood from the PTA. That, to me, brought home that you can have the best technology in the world, you can have the best all-volunteer program, but if you’re not getting a chance to sit down with Mr. and Mrs. Lozano and hear from them about the neighborhood, then you’re missing part of this.”

–

Many of the campaign’s events are solidly diverse, but they still fit something of a pattern. O’Rourke’s biggest fans tend to skew white, urban and progressive. At one event in DeSoto, an African-American neighborhood in Dallas an exuberant white woman in the front row rose to compare O’Rourke to John F. Kennedy, before an African-American woman in the back stood up to give a meandering statement about the difficulty of being both religious and a Democrat. At a rally in Lubbock a week later, an African-American student at Texas Tech gave O’Rourke partial credit while asking him to “walk the walk” more vigorously, whereupon the candidate described a new study about racial inequality he had seen in the news.

In February, O’Rourke held a town hall at a church in Greenspoint, a heavily non-white neighborhood in Houston. Senfronia Thompson and Sheila Jackson Lee were on hand to endorse O’Rourke, but the audience, many of whom were decked out in O’Rourke campaign swag, seemed to be significantly white. After O’Rourke spoke, a Korean-American college student who identified herself as a DACA recipient and activist, rose to challenge O’Rourke on his vote to end the government shutdown in January, which started when congressional Democrats refused to pass a spending bill without a DACA replacement. She was the second unhappy person to ask about the vote, and she was on the verge of tears as she did so. As photographers at the event came to capture the moment, a white guy sitting near her held up a “Beto For Texas” sign in their line-of-sight.

“I love your speeches, I love your videos, but what I need from you is your action. I’m here because I believed in you and I trusted you and I thought you would vote ‘no’ on this,” she said. “I thought you would have my back.” Immigrant activist groups had asked for Democrats to hold firm to their leverage, and O’Rourke’s decision to vote with the majority had left her feeling “betrayed and a little heartbroken.”

O’Rourke’s frank response was that while his heart bled for the plight of the Dreamers, Democrats didn’t have leverage. A vote to continue the shutdown would have been purely symbolic, an empty statement of principles. He was most likely right, but a lot of politics is symbolism. It’s one of several recent votes O’Rourke has taken that complicate his ideological profile, among them a vote to weaken critical post-crash financial regulations. (In recent months, though, O’Rourke has become much better known for his activism during the family separation crisis, so those votes may well disappear from the public consciousness.)

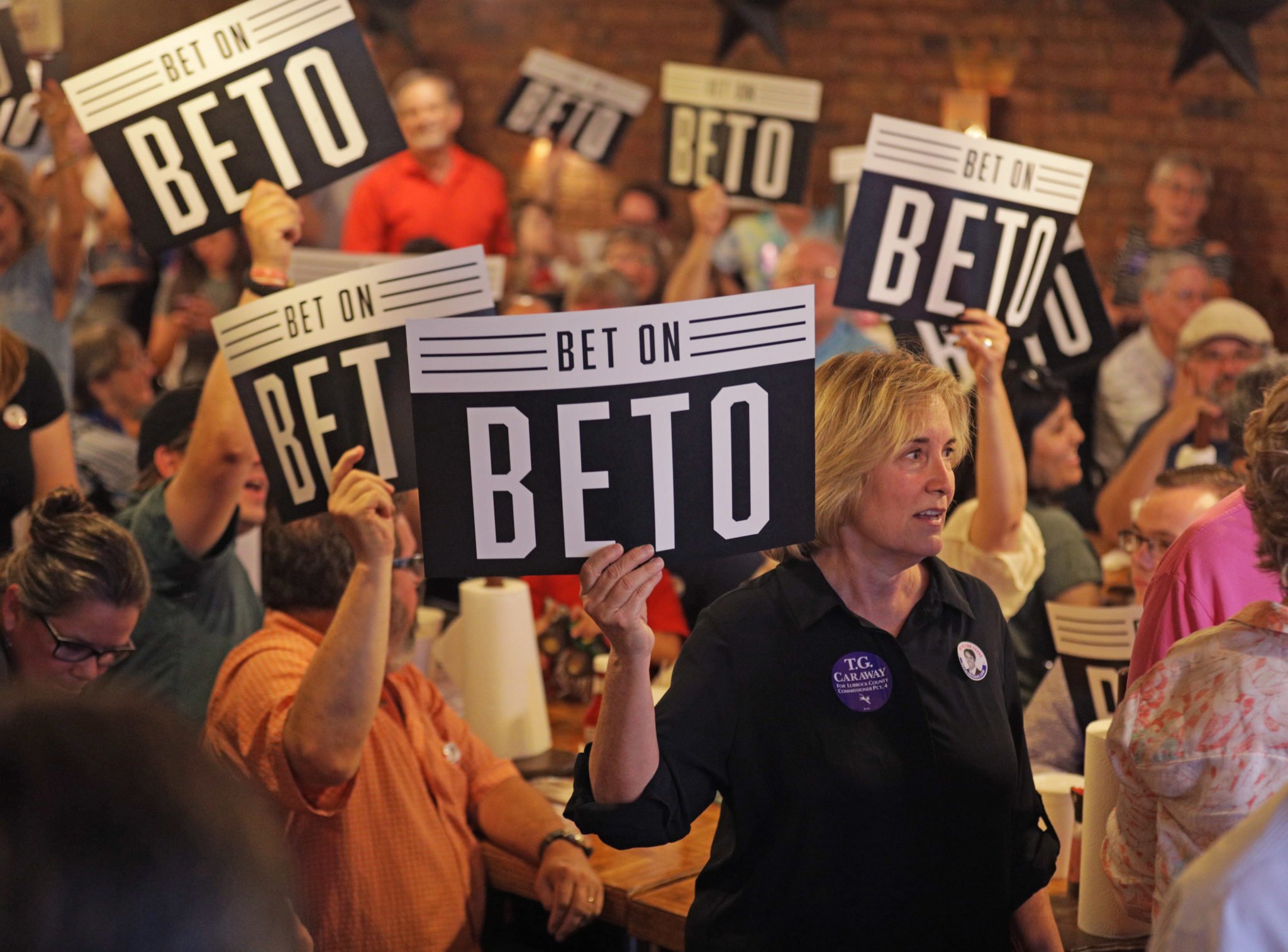

There’s a lot that O’Rourke is doing right. When I talked to O’Rourke in Lubbock last July, he spoke at length about how he hoped his campaign would change people’s outlook on politics. There was value, he said, in the simple act of coming together. We spoke the night of a town hall at a Lubbock BBQ joint. A couple dozen people came, a turnout that shocked people in attendance. It felt like a well-attended meeting of a neighborhood Democratic club in Austin. A couple of first-time candidates were there, milling around awkwardly. There was cake.

Nine months later, O’Rourke came back to Lubbock, this time drawing a crowd of 450 people to a ballroom at Texas Tech. The candidate spoke for 75 minutes to a diverse and rapt crowd, the front of his shoes hanging off the platform that had been erected for him. When the speech ended and O’Rourke offered to take pictures, a line formed that was so long it curved around the two back corners of the room. And one of those first-time candidates is here, this time with glossy campaign lit and a sharp suit.

In truth, people make too much of O’Rourke’s crowd sizes — it shouldn’t surprise us that many Democrats live in nominally Republican places. But the process of getting enlisted at these town halls can change people. Gracie Gomez, a middle-aged woman who says she used to consider herself a moderate — and apathetic — Democrat, says she “woke up with PTSD after the election.” She’d been walking blocks and making calls for Beto. “I thought I had been the lone Democrat,” she said, but she had come to realize how wrong that was. Before the meeting, she said, she’d been walking around Tech campus looking for people to recruit. She spotted a student that she stereotyped as a probable young Republican — young, white, clean-cut.

She almost didn’t approach him. “But I did anyway, and he was so grateful. He had no idea Beto was here,” Gomez says, as Taylor Swift’s “Shake It Off” starts playing on the ballroom speakers. “He started calling all his fraternity brothers to get them to come out.” In a year and a half, the place she lived in had come to look fundamentally different.

Correction: The original version of this story referred to Beto O’Rourke’s South Texas field organizer as Samantha Corté. Her name is Stephanie Corté. We regret the error.