One Undocumented Texas Family Flees a Hurricane for the Third Time

The road to recovery looks rough for Lorenzo and his family, but they're resolute about both the storm and anti-immigrant policies.

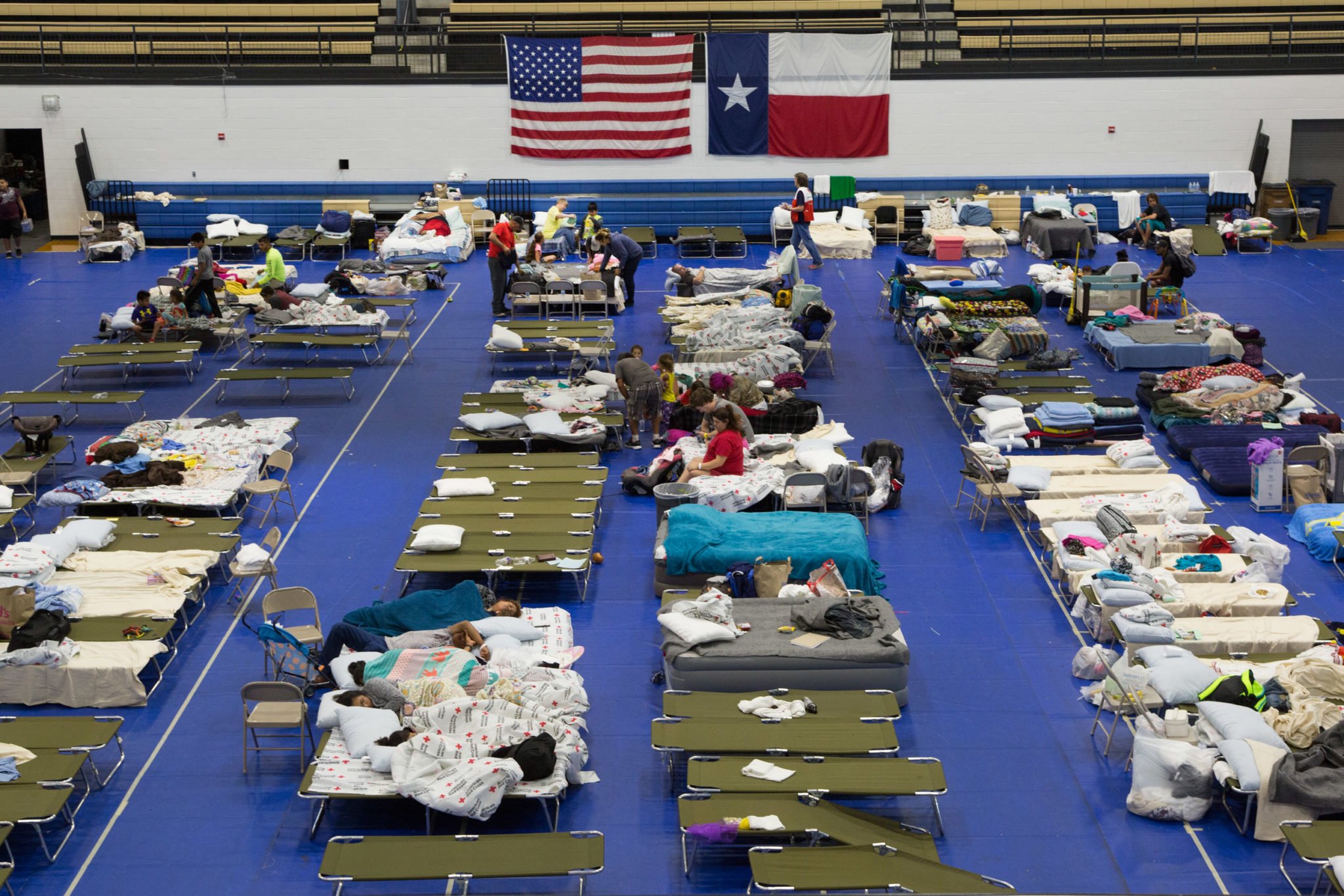

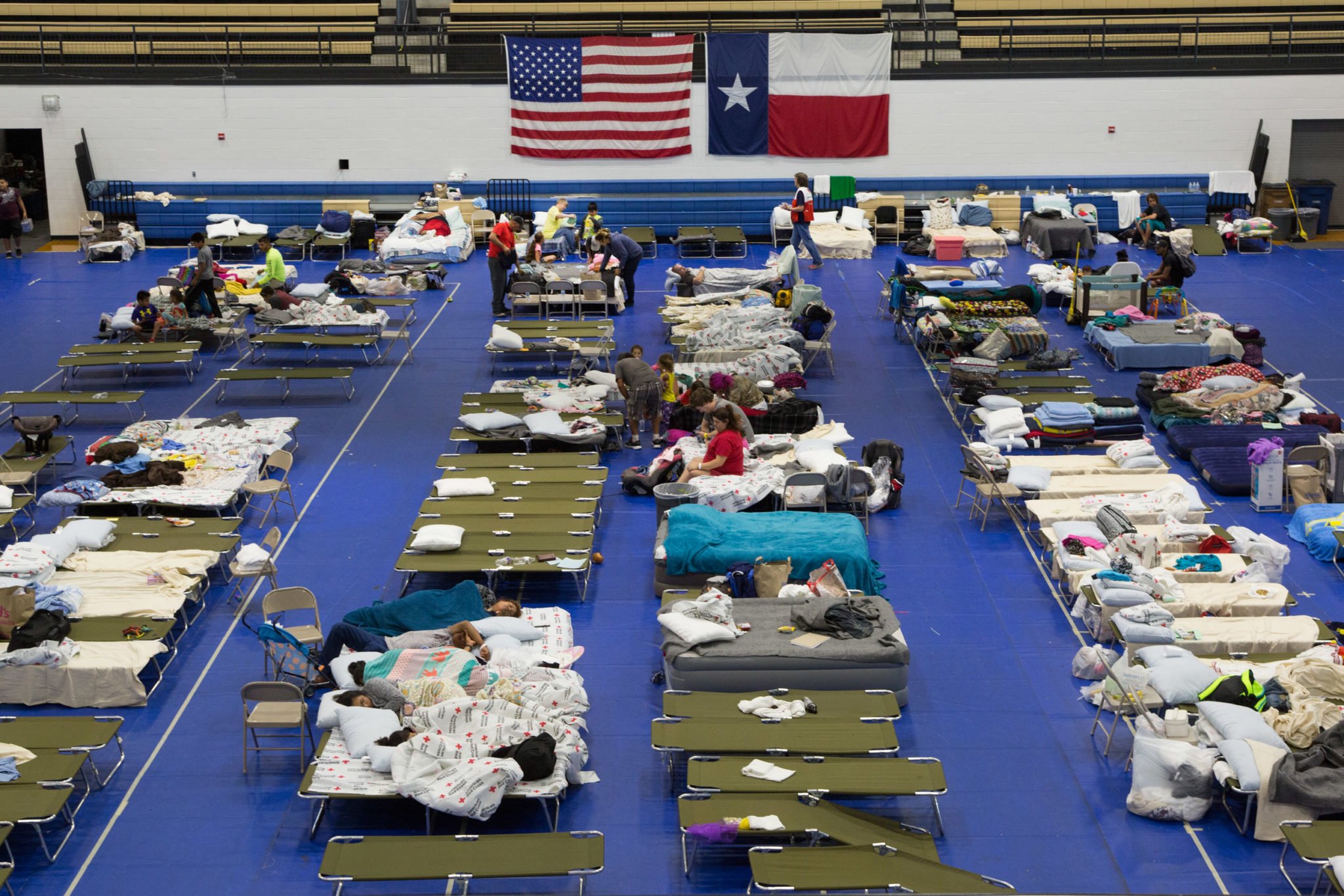

Both undocumented Mexican immigrants, Lorenzo and Paulina fled Houston Friday with their three children, leaving behind a mobile home a foot deep in water. Now they’re living with about 200 others in a shelter at the Delco Center in northeast Austin.

With Houston’s George R. Brown Convention Center well over capacity at around 9,000 people, Austin and other Texas cities have offered refuge to those who fled the historic Hurricane Harvey. More than 30,000 people are now staying in 230 shelters across Texas, a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) official said Wednesday.

Lorenzo and Paulina are among Houston’s estimated 575,000 undocumented immigrants. Unlike many, they didn’t believe rumors that emergency shelters would be asking for identification or aiding deportation agents: “We’ve done this before,” Lorenzo said.

Lorenzo said his family has evacuated Houston three times in their 17 years there, including when Hurricane Ike hit in 2008. By now, it’s almost a bizarre routine for them, so they weren’t afraid when they saw friends posting on social media not to seek assistance.

Enough fear has circulated about immigration enforcement during Harvey that officials have had to go to great lengths to tamp down the rumors.

“If someone comes and they require help and then for some reason [someone] tries to deport them, I will represent them myself,” said Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner on Monday.

Even Governor Greg Abbott gave immigrants tepid assurances on Friday, and FEMA has tried to quell fears in a section of its website titled “Rumor Control.”

Austin City Council member Greg Casar said there’s a reason the rumors have been hard to squash. “Austin police are not checking for immigration status at our shelters,” he said in a statement Tuesday. “However, I understand why people are afraid. Greg Abbott and Donald Trump have purposefully created this fear.”

Senate Bill 4, Texas’ “sanctuary cities” ban that Abbott championed, will take effect Friday unless a federal judge stops it. The measure will force law enforcement leaders to let cops ask about immigration status during any routine detention — for anything from speeding to jaywalking.

“The police have to do their job, but also there are bad people who will do their job badly,” said Lorenzo. Asked how she felt about SB 4, Paulina replied: “Tristeza” (sadness).

On top of SB 4, Trump could soon end Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), the Obama program that has granted relief from deportation and work permits to nearly 800,000 young immigrants. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has led the assault on DACA by threatening to sue the federal government if the program isn’t ended by September 5.

Lorenzo and Paulina’s oldest daughter, Maria, said she’s a DACA recipient who’s been in the United States since she was a year old. Now 18, she intends to start community college in the Houston area. If Trump fully terminates DACA, she could soon find herself back in a country she’s never known.

But like her father, Maria defies a common media narrative of the terrified immigrant: She said she’s scared, “but not really — whatever’s gonna happen will happen.”

As she spoke, Trump himself was about a 10-minute drive away on the second stop of his post-hurricane Texas tour. He toured the Texas Department of Public Safety’s Emergency Operations Center, where he was joined by about 200 protesters.

“It’s epic what happened,” said Trump earlier Tuesday in Corpus Christi, referring to Harvey. “But you know what: It happened in Texas, and Texas can handle anything.” He then waved a Lone Star flag in front of a cheering crowd.

The president, who has considered cutting FEMA to fund a border wall, made no mention of the mounting number of people killed by the storm.

Asked if he was glad Trump had arrived, Lorenzo pointed to a nearby Red Cross volunteer. “I think they’re the ones doing the helping,” he said.

The road to recovery looks rough for Lorenzo and his family. A construction worker, Lorenzo is the family’s sole breadwinner, and they’re already suffering from his lost wages. He doesn’t know when he can return to work, and he’s not sure they’ll even have money for next month’s rent.

He said he hopes to be back home by Friday.