Our Lady of the Underground

Whether you need love or money, safety or security, Santa Muerte is open for business—and business is booming.

Our Lady of the Underground

Whether you need love or money, safety or security, Santa Muerte is open for business—and business is booming.

by Asher Elbein

September 4, 2017

The first time Chris Muniz prayed to Santa Muerte, his life was spinning out of control. It was June 14, 2016, and his boyfriend had left him. An addiction to methamphetamines ate away at his cheery smile and burly figure, so much that his own mother didn’t recognize him. He passed the days working at a San Antonio dry cleaner and his nights shut up in his room, using. Isolation and drugs were destroying him, he knew. So when his boss took him to a South Side botanica — a retailer for folk medicine and magic — Muniz wandered the crowded aisles, past candles and spices, statues of Jesus and the Virgin of Guadalupe. He selected a little orange figurine, a feminine grim reaper with an owl at her feet and a scythe in her skeletal hands.

Following the store owner’s advice, Muniz took the figurine back to his apartment and set it up on a little coffee table with candles. He spoke the invocation, sat and began to talk about his heartbreak, his misery, his drug habit. But his words sounded hollow in the empty apartment. “I just looked at her a while,” Muniz says. “It was like, ‘This is a fucking statue, man. What the fuck is it gonna do?’ But then the candles started going a little weird.” All at once the feeling hit him: an overpowering and accepting presence that made him weep. It was like she was pulling the ugliness out of him, he says. Without quite knowing why, he began rubbing his tears into the figurine: his first offering.

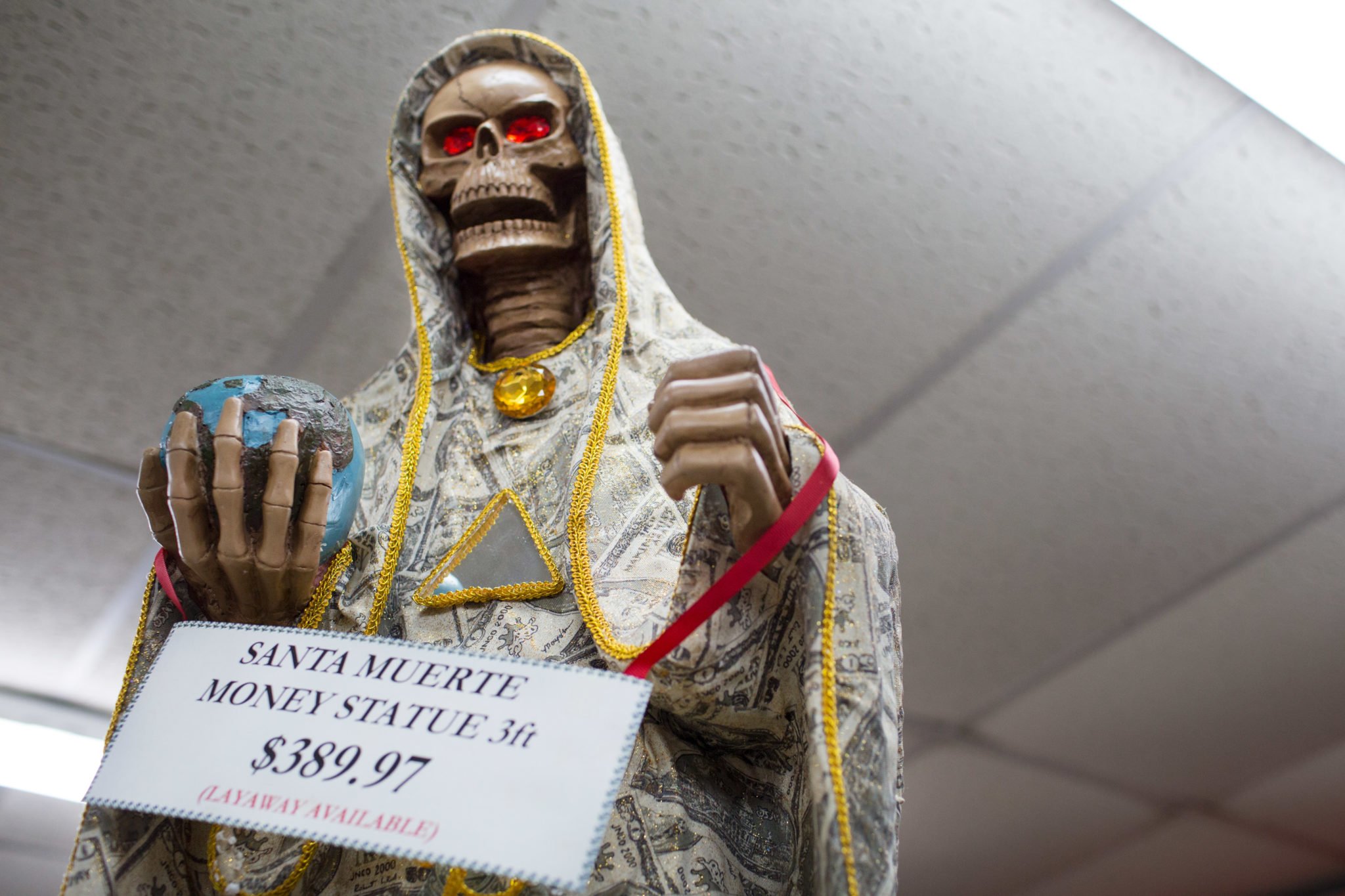

Santa Muerte — “Holy Death” — is at the center of one of the fastest-growing and most controversial new religious movements in North America. In the two decades since her mainstream debut, she’s attracted a global following of anywhere from 5 million to 10 million, a diverse collection of working-class Catholics, pagans, artists and immigrants. Bishops have called her blasphemous, drug cartels have adopted her image and the Mexican government has bulldozed her shrines. Yet her following only continues to grow, including in increasingly Hispanic Texas. Whether you need love or money, safety or security, Santa Muerte is open for business — and business is booming.

Santa Muerte began as many American spirits did: as a syncretic mixture growing in colonial soil. After the Spanish conquest of Mexico in the 1500s, open worship of underworld gods withered under pressure from the church. Deities like Mictēcacihuātl, the star-swallowing Aztec queen of the underworld, receded from view. But according to religious historian R. Andrew Chesnut, author of Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, The Skeleton Saint, the conquerors had unwittingly provided a replacement in their religious texts: La Parca, a female grim reaper popular in Iberian medieval traditions. What began as an artistic trope soon occupied the niche left by the vanished goddess. When a group of Catholic inquisitors were dispatched to Central Mexico in the 1790s to investigate the worship of a skeletal figure, Chesnut says, indigenous worshippers informed them its proper name was Santa Muerte.

The inquisitors destroyed the altar immediately, setting a pattern of public suppression that persisted for 200 years. While the veneration of Santa Muerte continued to evolve on the margins of Mexican society, in working-class homes and prison cells, it did so out of the public eye. At the dawn of the 21st century, Chesnut says, 99 percent of Mexicans had never heard of the skeleton saint.

That changed in 2001, when Enriqueta Romero, a quesadilla vendor from a working-class neighborhood in Mexico City, decided to place her life-size effigy of Santa Muerte outside her home after Halloween. Romero’s open display caught the popular imagination. Offerings of tequila and cigarettes began to pile up at the effigy’s feet, first from neighbors, then from visitors. As the years passed, previously circumspect devotees came out into the light and new public shrines appeared across the country. “I’ve never seen the religious fervor with other saints as I have with this saint,” says Eva Aridjis, a filmmaker from Mexico City and the director of the 2007 documentary La Santa Muerte. “People are more willing to openly worship her than they were several years ago. … Those who believe in her really believe in her.”

Driving that faith was Santa Muerte’s reputation for general miracle-working, Chesnut says. “She’s seen to personify death itself, which grants her greater power than any of her fellow folk saints,” he says. “You can ask her for any type of miracle or favor you’re after, unlike Catholic saints, who tend to specialize in only one or two types. And since she’s not a Catholic saint, she’s open to petitions and requests — and followers — that might not be welcome in Catholicism.”

The drug war also provided a boost. Much attention has been paid to Santa Muerte’s role as a “narco-saint,” Chesnut says, and the iconography of the folk saint is indeed popular with both cartel foot soldiers and leadership. Traffickers, smugglers and hit men often pray for successful missions and protection. (This association with organized crime led the Mexican government to bulldoze more than 40 public shrines near the U.S. border in 2009, prompting widespread protests from devotees.) But Santa Muerte also has a robust following among Mexican law enforcement, particularly policemen and prison guards. She attracts people whose lives are at risk, Aridjis says, and protects those who work in darkness: cabbies and street kids, prostitutes and petty hustlers, cops and soldiers. Many of her supplicants are poorer than average. Transgender women and other members of Mexico’s LGBT community are increasingly devotees. The vision of a powerful feminine death packs a visceral punch, Chesnut says: Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography reports an average of seven women killed by violence per day, perhaps part of the reason female followers outnumber men two-to-one.

“More than 200,000 people in Mexico have died [from violence] in the last decade,” Chesnut says. “There’s appeal in a saint of death at a time of great death, both for those doing the killing and those who fear they might be killed. She goes both ways.”

Santa Muerte also protects those who work in darkness: cabbies and street kids, prostitutes and petty hustlers, cops and soldiers.

Despite Santa Muerte’s growth, she still resides mostly in the shadows. In the United States, attempts to track her growth are hampered both by the complete lack of statistics and by the reticence of many of her followers. “Devotion on this side of the border is a lot more nebulous,” says Desiree Martín, associate professor of English at the University of California, Davis, and author of Borderlands Saints. “Many devotees are migrants who brought the religion over from Mexico, and it’s much dispersed and local. But just in my travels, looking through grocery markets and swap meets, there’s been a huge material rise in Santa Muerte products. I think you can find her now anywhere that you have a Latino supermarket. … It wasn’t like that in the U.S. several years ago.”

Texas’ few public shrines are attached to botanicas in big cities, such as Flores Spices in Houston, where dozens of Santa Muerte figures stand above piles of offerings and guttering candles. In 2013, a statue of Santa Muerte in a San Benito graveyard was smashed by vandals; that same year, a McAllen follower fended off anonymous attempts to have the shrine on her front lawn declared against city ordinances. “The closer you get to Mexico, the more prevalent it becomes,” says Janel Longoria, a devotee from Harlingen. “People will sell the figures or keep private altars. It’s very popular. But everything seems to happen behind closed doors.”

When Ana Marchand Maya was 6, her family left Mexico and moved to Harlingen. Growing up in the Valley, Maya heard that any person who prayed to “the devil” Santa Muerte would lose their loved ones. At 18, she married a man who turned out to be abusive. She ended up in a women’s shelter, undocumented, with three children to feed and no job prospects. When a friend suggested that she ask Santa Muerte for help, she hesitated, the old warnings heavy in her ears. But desperation got the best of her. With $3 in her pocket, she says, she bought a tiny stamp with an image of Santa Muerte and asked for a place to live. Within a month, she’d found an apartment. Other prayers followed: financial aid for the college where she (coincidentally) studied mortuary science, grants, help in moving her visa applications through the system.

She kept her new devotion quiet, though, fearing how her Catholic family might react. The Catholic Church has taken a strong stance against Santa Muerte, calling it a perversion of saint worship at best and Satanism at worst. In one typical broadside, a Vatican cardinal labeled Santa Muerte a “celebration of devastation and of hell” and warned that society needed to stamp her out. While American clergy have been more muted, bishops from San Angelo and El Paso have also condemned the folk saint. Soon after Maya became a devotee, her older brother was murdered, and her mother blamed his death on Maya’s veneration of the skeleton saint. It took them a while to work things out.

Nowadays Maya works as a bruja — a witch — from a big ramshackle house in west San Antonio. While she’s cultivated long-distance clients from places like New York and Virginia, the majority of her customers come from the south and west sides of San Antonio, where veneration has grown in recent years. Some are undocumented and are looking for protection against the cops or Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Others ask her to conduct weddings, baptisms and parties in Santa Muerte’s name. The walls of her home office are stuffed with Santa Muerte products: icons, amulets, homemade concoctions and votive candles with skeletal labels, plus ranks of statues that line the walls, windowsills and shelves in a riot of color.

“I try selling other saints, but none of them sell as well as Santa Muerte. She’s who people want.”

The different-hued robes align with specific requests and rituals, Maya says. Santa Muerte in purple turns back evil charms. Orange helps you kick a drug habit, red is powerful in love and blue helps a student study. The rainbow of figures on offer is both a tribute to the spirit’s multifaceted nature and a symbol of growing commercial demand. Most are manufactured in Asia and shipped to Mexico, where botanica owners buy them wholesale and have them shipped up to Texas. Maya gets hers direct from Mexico City and sells them to buyers across the country. New designs arrive every year: you can buy a sexy Santa Muerte with a miniskirt, or one with half of a face, or one gunning a motorcycle. “I try selling other saints, but none of them sell as well as Santa Muerte,” she says. “She’s who people want.”

The transactional nature of Santa Muerte’s worship is part of the appeal: You can ask for whatever you need, and offer whatever you have, without judgment. It’s an omnivorous and adaptable faith, one that can be practiced in the privacy of a home or out with a larger community, blended with Santería, Catholicism, paganism or atheism. In turbulent times, Santa Muerte offers recognition of three universal truths: that life is hard; that everyone could use a bit of help; and that everyone dies.

Just ask Chris Muniz.

The months following Muniz’s first prayers to Santa Muerte were transformative. He shed his addiction and began studying the folk saint’s ways and rituals. He became friends with the botanica owner who had originally sold him the statue, and he learned everything he could about her: how to read the synchronicities and decipher the visions by which Santa Muerte communicates; the significance of her scales, by which she weighs the merits of a request before deciding to grant it; her tendency toward jealousy and her wicked sense of humor. Eventually he began practicing as a shaman, though for a while he refused to accept payment. Now he consults with those seeking spiritual guidance, and is working with inmates in an Arizona prison to get Santa Muerte recognized as an official faith by prison authorities.

There have still been hard times. Muniz was diagnosed with HIV in November 2016, and a depressive relapse led him to attempt suicide a few months later. But Santa Muerte was with him on both occasions; on the first, she answered his prayer to help him find a free testing clinic. And on the second? “I was dead for a little bit there, and they brought me back,” Muniz says. “I didn’t see no lights, and I didn’t see no tunnels. All I saw was something very black, and a voice. And the voice said to me, ‘You think it’s so hard? Go back and try again.’”

Asked to describe how he sees Santa Muerte, Muniz pauses. We’re sitting in the house of one of his friends, and Muniz has prepared part of an invocation, lighting a votive candle and a tiny brazier, laying out his tarot cards and a pair of hand-rolled cigars. On the shelves, his friend’s Santa Muerte figurine overlooks tiny bottles of vodka and tequila. He’d prefer not to speak for her, Muniz says, and he shuffles the cards. He rings a bell and speaks the rest of the invocation, calling down Santissima Muerte, the Most Holy Death, to guide his words.

Smoke coils from the tiny brazier. The candle flickers as from the passage of wings. After a long moment, Muniz speaks. He describes her not as a folk saint or lesser spirit, but as the holiest of the archangels, born out of the first murder, and carrying everything in herself that came from it: rage, sadness, mystery, the cry for help. That is why she is a spirit of last resort, a patron of those who’ve lost their way.

“She’s nothing but love,” he says. “She’s not evil. … I find a lot of love in her. I’m not a narco. I went to her to help me get away from drugs. But the narcos will go to her for protection, too. She doesn’t discriminate. That’s why the LGBT can go to her, the Roman Catholic can go to her. Death accepts everybody.”