Texas’ Strange Brand of Cool

Revisiting 'Paris, Texas' — the film that made nowhere hip.

A version of this story ran in the April 2016 issue.

Over the years, many people and places in the Lone Star state have availed themselves as the butt-end of jokes for the rest of the world, but none so concisely as Paris, Texas. Not that anyone’s ever had anything against the Red River cotton town; on the contrary, few know much about it except that it’s Podunk. That’s the point. The city’s name is the perfect one-liner, in and out in four syllables. The setup: Paris, city of light, birthplace of human rights, modern dream of a world capital, the spiritual homeland of all artists and intellectuals regardless of national origin. Then the punchline: Texas, land of 10-gallon hats and pea-brained politicians, football and cheerleaders, where oil cartels and fundamentalist Christians find common cause against science and humanism, and where highbrow art and literature are still about as unwelcome as a salsa brand from New York City.

This was the prevailing attitude when the German arthouse film director Wim Wenders made Paris, Texas in 1984, and it continues to apply today. I still hear people make the joke, still sense the kneejerk scorn of friends and colleagues from California, the East Coast and Europe. Earlier this year, however, when I revisited Paris, Texas at the Austin Film Society’s retrospective on Wenders’ life work, it was impossible not to feel that something had changed. Paris, Texas invented a certain flavor of Texas cool, an updated take on the archetypes of the state (men wandering out of the desert, trailer-park romance, drive-up banks and neon roadside diners) that appealed to cultured outsiders more than the stale cowboy imagery Texans have preferred as a frame for their identify.

These days, urbane “Texas cool” is an internationally recognizable brand of its own. Austin in particular is full of people (me, for one) who might call Paris, Texas their favorite movie about the state. The fact that the Austin Film Society could put on a Wenders retrospective and have so many people show up is a case in point.

Don’t get me wrong: Austin is still no Paris, France — especially not in the romantic, center-of-the-world sense. Neither is Houston or Dallas. But we’re not the middle of nowhere either. Or, if we are, nowhere itself has changed, become somewhere.

When the drifter character in Paris, Texas, played by Harry Dean Stanton, wanders out of the desert in the first scene, he finds himself in Terlingua, a nowhere town if there ever was one. Now, Terlingua is a tourism stop for art lovers and nature buffs on the Marfa-Big Bend circuit, a short distance from the private ranch where U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia died in luxury.

You could look on this change with dismay, as the relentless advance of hegemonic global culture snuffing out whatever’s genuine and local. That’s certainly a valid interpretation with undeniable truth in Austin, where newcomers have changed so much so quickly. Visit a fancy East Side restaurant late at night on a weekday and you’ll likely hear European languages and accents — a slice of gay Paree in Texas, and the subject of much local angst, especially from displaced minority communities.

Paris, Texas invented a certain flavor of Texas cool, an updated take on the archetypes of the state (men wandering out of the desert, trailer-park romance, drive-up banks and neon roadside diners) that appealed to cultured outsiders.

The boy is obsessed with Star Wars, and, like Luke Skywalker, he discovers that he pertains to a more epic family history than he’d previously thought. Dad and Mom aren’t the billboard company executive and fretting housewife he grew up with in the L.A. ’burbs; they’re a couple of hard-ass Texans too busy with their wild sorrows to bother raising a small child. Early in the film, the boy refuses to walk home after school with his newly-arrived father because, in his California town, “nobody walks.” Little does he know that his father walked across the Chihuahuan Desert.

As a non-native Texan, this is the layer of the film I gravitate to most. The same is probably true of a lot of my fellow newcomers. The film evokes a sense of excitement about suddenly belonging to something as big and strange as Texas. In a sense, it’s the same frontier fantasy that makes Texas cowboy movies work. But where many modern-day Westerns mourn or ignore the reality that the frontier has been closed for a century-plus, Wenders, Shepard and Carson locate a new kind of frontier promise. It’s the same pulse that seems to draw in human tumbleweeds, including a great number of artists, intellectuals and other freethinking refugees, from coastal cities in greater numbers every year.

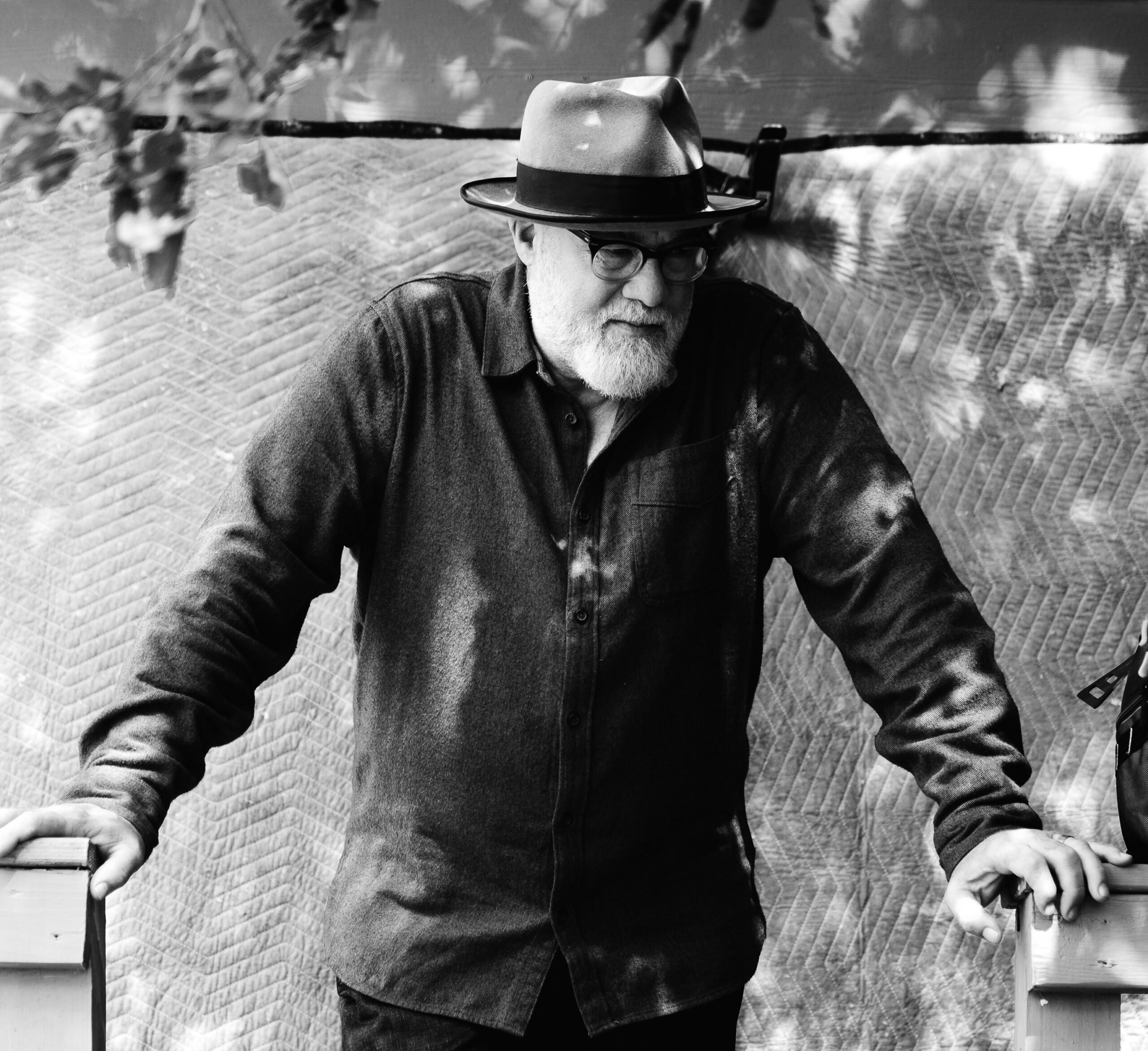

[Featured image: Nastassja Kinski and Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas (1984), courtesy of Criterion Collection.]