Past the Pursuit of Pretty

"Caterpillar," Liza Mandelup’s recent documentary, unearths the humanity in cosmetic surgery.

This is part of our coverage of South by South West (SXSW) 2023.

We typically understand documentaries as analytical, perhaps even diagnostic by nature, such as popular Netflix series that examine “cold” murder cases. On the other hand, we have nature documentaries narrated by David Attenborough that capture the seasonal majesty of the Okavango Delta.

It would be easy to assume that a documentary on medical tourism and beauty standards might take a direction closer to the former example. One might expect an exposé on the damaging influence of social media, the ridiculous cost of healthcare in the United States, or a scandalous story in which the real demons are revealed to be avaricious CEOs and immoral marketing campaigns.

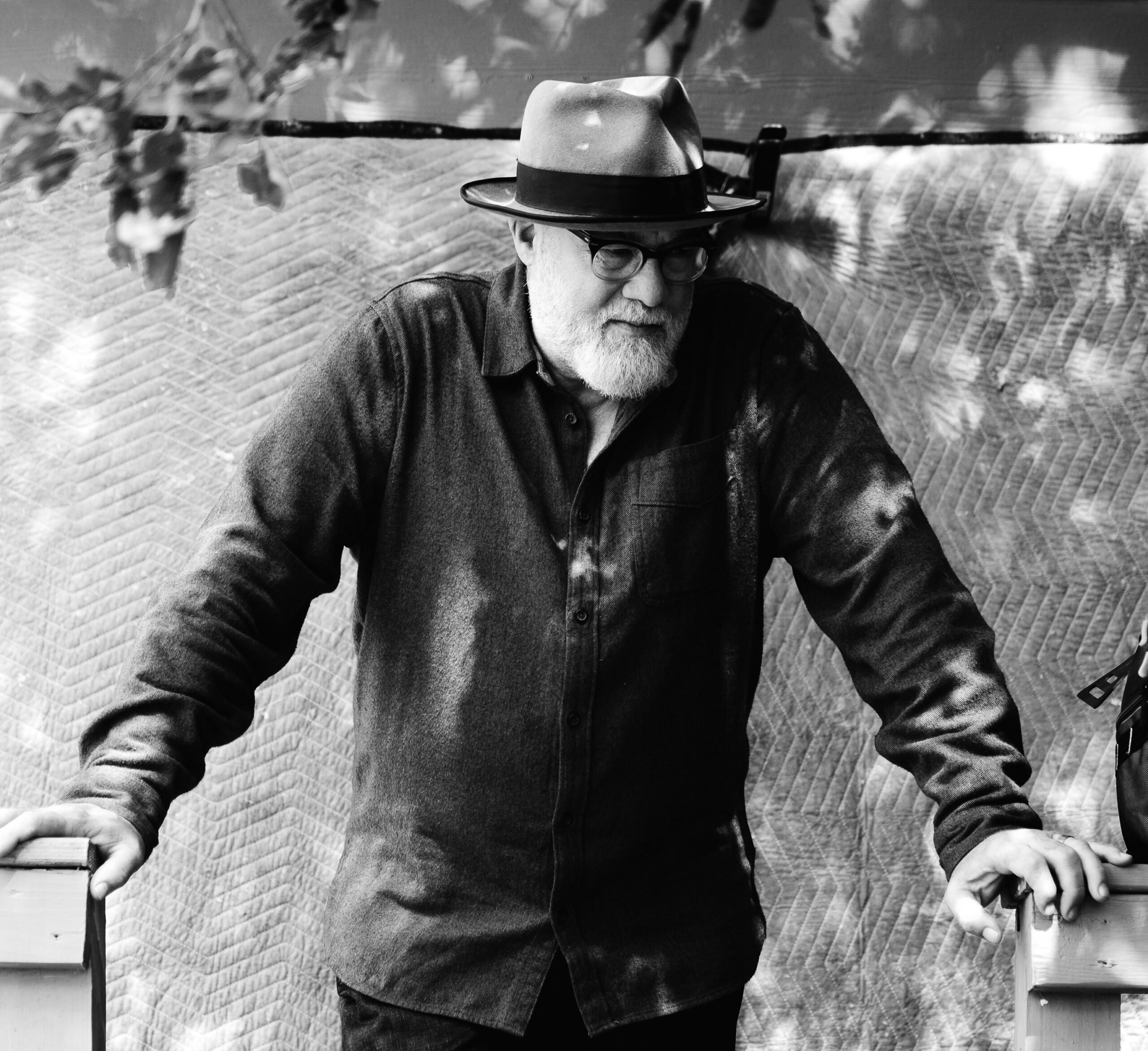

Liza Mandelup delivers all and none in her documentary, aptly named Caterpillar. Throughout the film, she shares a much more humanist vision—one about the quest for self-discovery and empowerment. Subjects of her earlier documentaries such as Jawline, which follows a young aspiring influencer, touch on the cost of “pretty and perfect.” Her short documentary Nowness explores Savage Ranch, a sort of retreat for those wishing to delve deeper into their queer identity. Sundown follows a group of “night children” who live with xeroderma pigmentosa, an allergy to sunlight, and attend a camp created specifically for them. Mandelup seems taken with individuals wanting to belong.

In Caterpillar, Mandelup focuses on David, an insecure gay man living in Florida, where he lives an otherwise unremarkable life. He dances at clubs and cuts his mother’s hair. Their relationship is tenuous. As they talk during one of their styling sessions, one senses the arrested anger of a man still struggling to love his mother, and his baffled mother can only say all the wrong things. Every other word is a trigger. David is haunted by his past but cannot find promise in his future. It is certain: Here, now, like this, he cannot move on.

Then he discovers the company BrightOcular, which offers to surgically change the color of his eyes with an implant for free in exchange for his customer testimonial. The catch is he must travel to India for the operation. After watching the stories of people who have already undergone the procedure, he decides this is what he needs: fresh eyes for a fresh start.

Our odyssey with David into the land of cosmetic surgery feels much more like a hero’s journey of old. One must admire his tenacity and steadfast belief that it is through this trial—for no invasive operation is without risk—that he will metamorphosize.

Though one should never conflate correlation with causation, there does seem to be a strong cause-and-effect relationship between physical attractiveness and the attention one receives. David sums it well: “Sometimes, the way you look matters.” Attention correlates positively with opportunity—be that professional, social, or personal—in the case of David, who needed a reason to be the person he wants to be. He says, “Changing me will change my outlook on life.”

Our culture makes those who don’t have skinny waists, washboard abs, or stunning eyes feel terrible about themselves. Would that one could avoid taking the Lord’s name in vain here, but Jesus Christ, let us count the number of Americans who routinely travel to Mexico for cheap Botox. A prescription from a licensed medical professional is not required to acquire testosterone, anabolic steroids, or other “performance enhancing” substances at farmacias, as popular a destination for tourists as any off-the-beat cenote. In a recent trend on social media, some fitness content creators admit that they are not “natty,” or natural, meaning that they did not achieve their muscularity with discipline and diet alone. Admittedly, this is something that should be discussed openly, but should we normalize this behavior? Gay men such as David are especially vulnerable to body dysmorphia and eating disorders due to the sky-high toxic beauty standards present in the gay community.

Watching a film like Caterpillar makes it more difficult to judge others for altering their body for cosmetic purposes, and this is where Mandelup should be lauded. David could easily be written off. It’s easier to sit on a seat of self-righteousness than to see what all our struggles have in common. Why does he need to change the color of his eyes to be happy? As we learn more about David, we find empathy.

Often, our culture likes to paint cosmetic surgery—body modification in general, if we’re honest with ourselves—as a pursuit of vanity. Something so banal as a body piercing is often equated to the desecration of a temple. But in some cases, namely gender dysphoria (frequently experienced by transgender people, for the uninitiated), body modification is recommended by medical experts. Despite demonstrated improvements in quality of life and lower suicide rate of those that have undergone gender reassignment, our society balks at it.

Culture, politics, and religion aside, our bodies are just that, our bodies.

It’s no secret Republicans are waging a culture war against anyone who’s not on their side. Anyone who grew up attending Sunday school or vacation Bible school—hallmarks of Southern Baptist indoctrination—has been spun the idea that our bodies are temples. Besides connoting that we should not “defile” our bodies with the obvious drugs, sex, and rock and roll, this idea also implies that we do not have ownership of our own bodies.

Culture, politics, and religion aside, our bodies are just that, our bodies, to do with as we please. Besides, as American life expectancy continues to fall, doesn’t it make all the more sense to take advantage of what we have while we have it? Since we’re here for such a short time, and if we aren’t satisfied with what we have, why not try to make more of it?

Maybe the story of David and BrightOcular isn’t about becoming more attractive. It’s certainly not a dissection of beauty standards. David’s sojourn to India for cosmetic surgery is comparable to a spiritual pilgrimage, for it is his faith and conviction in the promise of what comes after that carries him. Maybe all David wanted, what all of us want, is permission to be.