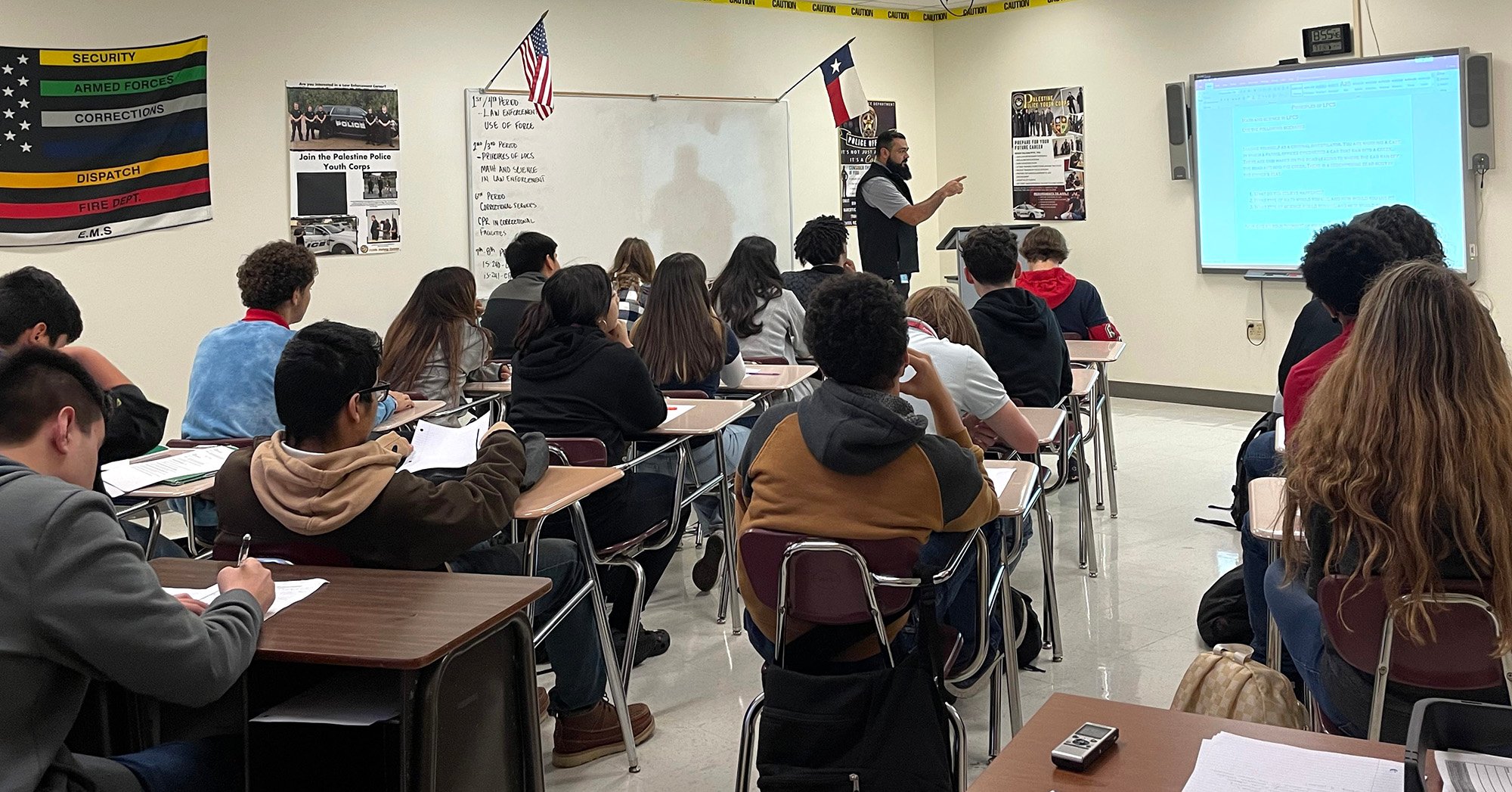

‘The Penal System Today is Slavery’: Lawmakers Finally Start to Talk About Unpaid Labor in Texas Prisons

The 13th Amendment left a loophole for prisoners to be forced to work without pay. Texas remains one of five states that exploits the carveout for state profit.

Inmates in Texas make license plates, grow crops, tend to cattle, make soap and clothing, refurbish buses and computers, build furniture and more. They’re required to work if they’re physically and mentally capable, and the vast majority work for free — making Texas one of only five states where regular prison jobs are unpaid.

Though efforts to create a minimum wage for inmates failed this session, advocates for criminal justice reform say they’re encouraged to hear conversation in the Capitol about inmates being forced to work for free, and hope the discussion sparks action next session.

In early March, the House Committee on Corrections considered a resolution by state Representative Ron Reynolds, D-Missouri City, to honor the Convict Leasing and Labor Project. The activist group fought to memorialize the remains of 95 people believed to have been black victims of the convict leasing system, through which prisons leased out inmates to private companies after the Civil War. The remains were uncovered at a Fort Bend ISD construction site in 2018.

At the legislative hearing, state Representative Phil Stephenson, R-Wharton, asked Reynolds if anything resembling convict leasing is still happening today. Houston Democrat Alma Allen, vice chair of the committee, explained that though the 13th Amendment, ratified in 1865, abolished slavery and “involuntary servitude,” it allowed an exception for people convicted of crimes to be subject to forced, unpaid labor.

This exception laid a foundation, built on by racist Jim Crow laws, for the convict leasing and mass incarceration of ostensibly free black southerners, including in Texas. Even after the Legislature passed laws to end the state system of leasing people to companies for a profit in 1910, no pay for forced work is still the norm in Texas prisons more than a century later. Meanwhile, a third of the state prison population today consists of African Americans, who make up 12 percent of the general state population. And almost half of those inmates are serving time (and working for free) for nonviolent charges.

“The penal system today is slavery,” Allen said during the committee hearing. “It is a legal way to enslave people.” While the substance of the comments is well-known to experts, hearing them from a legislator at the Texas Capitol is proof that the conversation around criminal justice reform is advancing, said Doug Smith, senior policy analyst for the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition.

State Representative Victoria Neave, D-Dallas, had already been working on legislation to require the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) to pay prisoners $1 a day, about the national average, for their work. She told the Observer that she’d started researching the issue after being appointed to the corrections committee in January, and she filed House Bill 3720 after the committee’s discussion in March. It was an effort, she said, not only to compensate inmates for their work, but also to “improve a person’s chance of successfully reentering society upon release.”

Texas has one of the largest prison populations in the country, with more than 145,000 prisoners in 2017. There are almost 900 people incarcerated for every 100,000, while the national average is 698 people incarcerated per 100,000 (and less than 100 people imprisoned per 100,000 in several European countries). Texas also has one of the most profitable prison systems in the nation: Texas Correctional Industries (TCI), the state’s prison labor program, made $84 million with the help of free labor in 2017.

Inmates who work for private companies through the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program do earn wages, though Jason Clark, TDCJ’s chief of staff, said about 80 offenders — significantly less than one percent of the state’s prison population — participate in that program.

Neave’s bill was heard in committee in April and left pending; now that the deadline for House bills to be advanced from the lower chamber has passed, the bill is going nowhere this session. But Neave suspected that would be the case when she filed it. Her intention, she said, was to start the conversation about unpaid labor in prisons. Neave successfully used a similar approach on legislation to strengthen the state’s sexual assault laws, including a high-profile, bipartisan measure that is touted as the panacea to the state’s untested rape kit crisis.

After the legislative session ends, Neave said she will submit a formal request to House Corrections Committee chair James White, R-Hillister, to study the issue in the interim. But it’s up to House Speaker Dennis Bonnen to direct an interim charge on inmate pay. Bonnen’s office did not respond to requests for comment from the Observer.

Like any bill that asks the state to fork over money, Neave’s proposal will face an uphill battle. The TDCJ estimated Neave’s bill would cost the state $31 million a year. TCI’s annual gains of more than $80 million come in part from selling products and services made by prisoners working for free. But, Neave said, the state could pay prisoners and still make a net profit.

She said she sees the proposal as an investment in reducing recidivism. But White, who sets the agenda for the committee, put it bluntly: “I don’t like passing out bills with a fiscal note. Fully funding public education, getting these property taxes down, I think that’s what I’m [at the Legislature] to do primarily.”

Smith, of the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, was equally frank in his assessment of Neave’s bill. “No legislator is going to seriously consider spending [$31 million] to pay someone incarcerated during this session,” he said. He likened the issue to another reform effort this session — installing air conditioning in prisons, a subject of civil rights lawsuits. A bill by Edinburg Democrat Terry Canales would have required TDCJ to keep its units between 65 and 85 degrees, but it was watered down to call for a cost study after TDCJ estimated the measure would cost $1.2 billion.

“Just lower your damn prison population, and you can afford to run a prison system that doesn’t torture people.”

There are multiple necessary reforms in the criminal justice system, Smith said, but the root problem is harsh, punitive laws that prop up mass incarceration and often target low-income people and people of color. The state would have more resources to go around if fewer people were imprisoned.

“Just lower your damn prison population, and you can afford to run a prison system that doesn’t torture people,” Smith said. “That’s exactly the prison system that most of the developed world has, and you get there by decreasing your prison population substantially.”

But Texas has moved slower than most in reforming its drug laws, which account for at least a sixth of the state’s prison population. For example, less than 24 hours after a historic vote in the Texas House last month to stop arresting people for low-level marijuana possession, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick declared the bill dead on arrival in the Senate.

Lauren Johnson, the criminal justice outreach coordinator for the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas, said she was heartened by the corrections committee’s lengthy discussion about prison labor, including Stephenson’s gobsmacked reaction to the concept that inmates work for free. In fact, the Republican freshman representative signed on to Neave’s bill.

“We’ve got an opportunity to work with the members and really come up with some solid solutions,” Johnson said. “Having a solid financial foundation when you return home [from prison] could be a game-changer for people.”