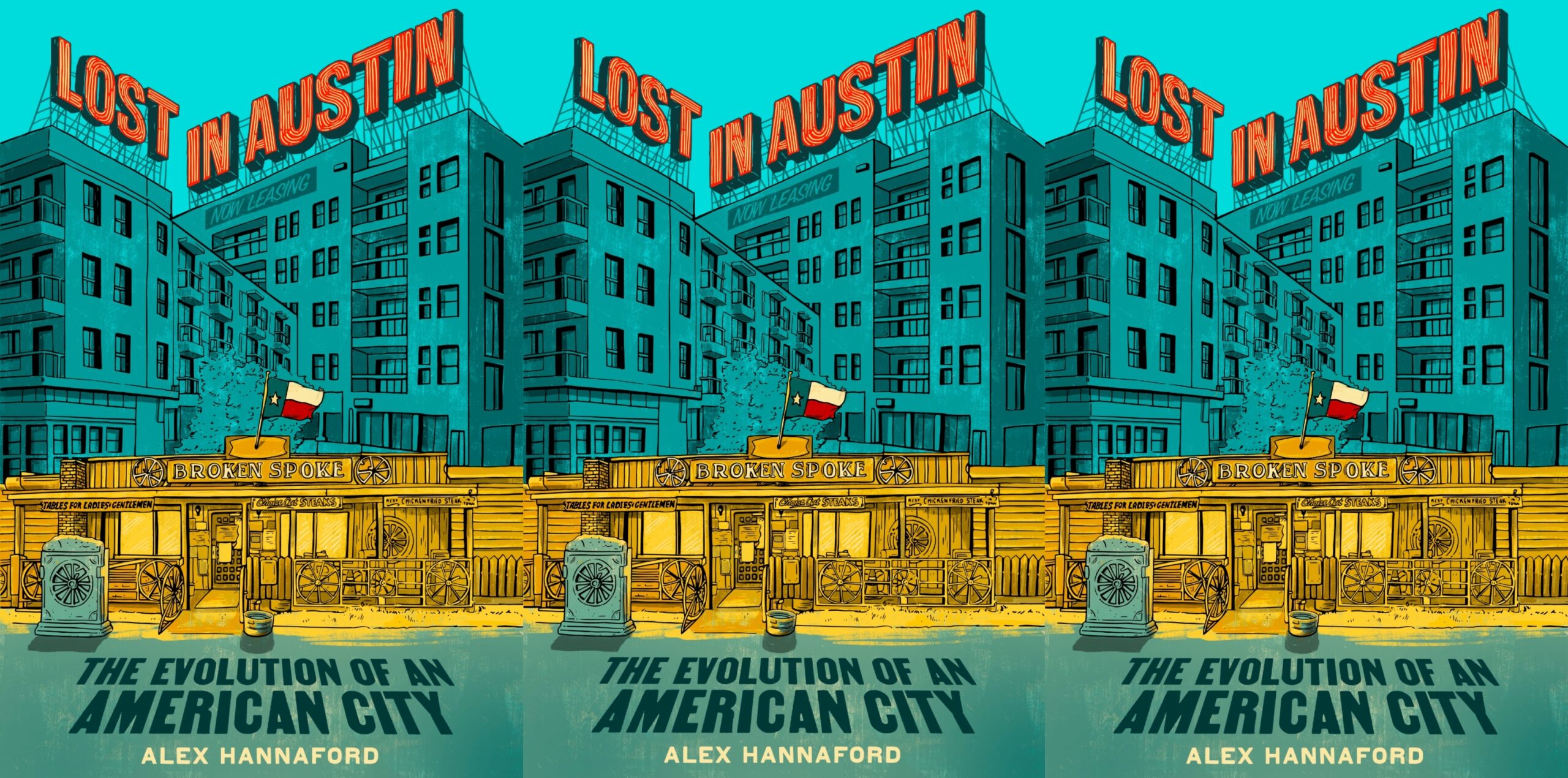

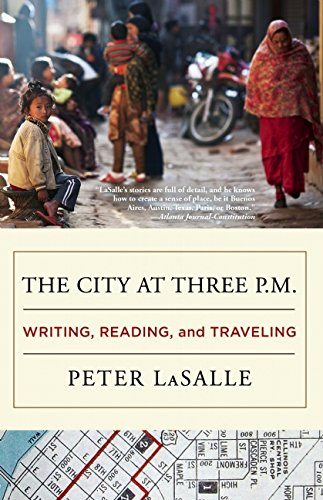

Peter LaSalle Seizes the Day

The ordinary particulars of being a person figure into LaSalle's new collection of essays, which bucks the obnoxious disembodied quality that sometimes afflicts travel writing.

A version of this story ran in the February 2016 issue.

Peter LaSalle

DZANC BOOKS

264 PAGES; $15.95 Dzanc Books

So you have this friend. He’s what you would call a good guy: fun to be with, unassuming in his black-and-white Reeboks and Red Sox cap, a fine storyteller. But “good guy” doesn’t quite capture the force of his conversation, his capacity to awaken that part of you that’s endlessly curious. After an hour in his company, you’ve forgotten about your beer and are instead filling your moleskin with lists titled “Books!!” “Places to visit,” “Shit I need to learn” and “Where to stay in Tunisia.”

Even if you don’t have the good fortune to know Peter LaSalle, who is something of an institution at the University of Texas at Austin English department, you’ll feel like you do as you read the essays gathered in The City at Three P.M.: Writing, Reading, and Traveling; it’s a miscellany of nonfiction pieces ostensibly connected by their concern with the three items mentioned in the book’s subtitle. In fact, what unites the essays is the author’s vibrant personality and the vehemence of his literary opinions. The ethos of the collection might be summed up as follows: Our days are numbered and we better damn well make them count, which for LaSalle means traveling some and reading as much as possible.

The essays in The City bespeak enthusiasm, optimism, appreciation, energy. These may not be the qualities we actually exude when we travel (I, for one, am guilty of sitting on my hotel bed watching HGTV’s “Love It or List It” when I mean to be out exploring), but they’re what we aspire to. As readers, we get to feel virtuous just by following LaSalle’s adventures and tapping into his utterly unpretentious erudition. “The Saul Bellow Speeding Ticket” tracks a young LaSalle to the University of Chicago; he has enrolled in an MFA program for the sole purpose of getting close to Saul Bellow, only to discover that Bellow doesn’t even teach in the English department. Other essays transport us to Buenos Aires (chasing Borges’ ghost), Tunisia (excavating scenes from Flaubert’s Salammbô), Mexico City (reflecting on Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano), and Hollywood (“on location” with Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust). In addition to these brisk, place-focused essays, there are a handful of more overtly experimental pieces. It makes for a compelling mix, so much so that I wish LaSalle and his editor hadn’t shoehorned in three journalistic pieces from the 1970s, which appear under the heading “World Lit — My Early Classes.”

At UT-Austin, LaSalle’s decades-long tenure as a creative writing professor has shaped sensibilities and whet literary appetites. To see what his fiction does with the wide-ranging locales he describes in The City, pick up his luminous 2014 story collection, What I Found Out About Her. And while you’re at it, get your hands on Mariposa’s Song, LaSalle’s 2012 novel. Written as a single, endlessly unspooling sentence, the novel is an unforgettable achievement of character, setting and style that explores the precarious existence of a young Honduran immigrant working as a B-girl in a seedy East Austin bar.

The essays have the feel of a conversation so lively that it can’t quite get to the end of a story before branching out into new, equally interesting, topics.

LaSalle isn’t one to force insights; he notes instead that “Big Realizations … don’t come along very often, for boneheaded me, anyway.” He accomplishes something both subtler and more compelling: He positions ordinary moments, lucidly described, as part of a larger web of meaningfulness, which he calls, somewhat cryptically, “the metaphysic.”

More than anything, LaSalle makes us want to be worthy of the books he loves. He does his bit to counteract the crass machinery and “shabby commercialism” of U.S. publishing by peppering the essays with literary appraisals (e.g., whose stock has risen too high, who we ought to know about but likely don’t). Some introductions are more deliberate, as when LaSalle lingers for a few pages on Texas writer William Goyen, whose The House of Breath I can also vouch for (it forever altered how I see my native East Texas). After a passage from Under the Volcano, LaSalle coaxes us toward an appreciation of the novel’s “full prose that wears the old heart on the sleeve,” offering a mini-lecture that, for any English majors out there, will likely recall early and enraptured encounters with literature.

LaSalle is that rare writer of supremely readable prose who also has genuine respect for the lyrical. Goyen’s influence shows in the dreamlike passages of “Two Short Movies” (on Hollywood and Nathanael West), although our narrator quickly dismisses them as “pseudo-Faulknerian parenthetical riffs.” In addition to continuing the self-effacement mentioned earlier, these metatextual interruptions keep the writing in The City from turning precious. And it’s often by disrupting the very enchantments he weaves that LaSalle pivots from absorbing place descriptions to more personal topics. The ordinary particulars of being a person — aging, taxes, bills, sunburn and thirst — all figure into the essays, ensuring that they buck the obnoxious disembodied quality that sometimes afflicts travel writing.

“There’s no friend as loyal as a book,” Hemingway once declared. Sure, it’s the kind of remark that, embarrassingly, gets emblazoned on tote bags and bookmarks, but that does nothing to undercut its basic truth. The essays in The City return us to the best of ourselves, reminding us how much we care about books, ideas, culture, travel. And because LaSalle is such a good guy, he never makes us feel bad about forgetting in the first place.