Plight at the Museum

The best Texas history museum you’ve never heard of is staring down a financial crisis. Will it survive?

–

by Rose Cahalan

January 7, 2019

“Let me show you some of my favorite things,” says Bill Green.

It’s just before 10 on a chilly October morning, and we’re standing in the entryway to the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, 19 miles south of Amarillo. Outside, on the campus of West Texas A&M University, students hurry to class in a persistent drizzle. Inside, museum employees are arriving, and several stop to say hello to Green, who was the history curator here from 1993 to 2010 and still wears his staff name tag. Now 75, he walks slowly and speaks quietly, but there’s an intensity to his piercing hazel eyes, which quickly scan whichever artifact or person he’s studying. Green, who has a neatly trimmed white mustache and wears suspenders over a plaid shirt, still works as a freelance public historian; he regularly makes the two-hour drive to another museum in Canadian, where he’s curating an exhibit on the history of Hemphill County.

Today he’s only got an hour to spare, and he doesn’t want to waste a minute on small talk. As he ushers me into the galleries, he reels off a litany of the museum’s collections: “History, natural history, Native Americans, anthropology, we have paleontology, world-class art, textiles, petroleum, automobiles, windmills.” Yet few Texans know that this is the state’s largest history museum, by both number of artifacts (nearly 3 million) and square footage (285,000). Its scope includes not just Texas, but the entire Panhandle-Plains region — a vast swath of land extending into Oklahoma, New Mexico and Colorado.

The first exhibit most visitors see is “People of the Plains,” which Green helped design. Its breadth is sweeping: arrowheads made by the region’s earliest inhabitants, who arrived 14,000 years ago, sit not far from a reproduction of a 19th-century settlers’ chuckwagon. Green leads me from object to object, lovingly describing the work that went into each one. Pausing in front of a resin re-creation of a bucket of food, he explains that it’s son-of-a-gun-stew, often made on cattle drives to use up the organs of a freshly slaughtered calf before they spoiled. “I cooked it up myself, froze it and mailed it to the company that did the reproduction,” he says, pointing out the white chunks of brain.

“I don’t know what’s to become of the museum. … This place is one of the best-kept secrets in Texas.”

A large glass case displays watches, a pistol and a Bible owned by Charles Goodnight, perhaps Texas’ most famous cowboy. Around the corner, there’s a wheel that visitors can spin to try their luck as farmers, landing on drought, an economic downturn or a bumper year for cotton. The only time Green cracks a smile is in front of a diorama depicting the traditional Plains Indians method of skinning a buffalo; a bloody video shows two of their descendants demonstrating how to use every part of the animal, turning the bladder into a canteen. “Kids go nuts for this stuff,” he chuckles.

Green scowls, though, as he peers through a viewfinder at color photos of early-20th-century kit houses, the simple clapboard homes where Panhandle settlers lived: “These slides have faded. We need to redo ’em.” When we reach a 1966 Ford Mustang that visitors can climb in and spin the wheel, he runs a hand over the leather seats, which are coming apart at the seams. “You can tell it’s been ridden hard and put up wet.”

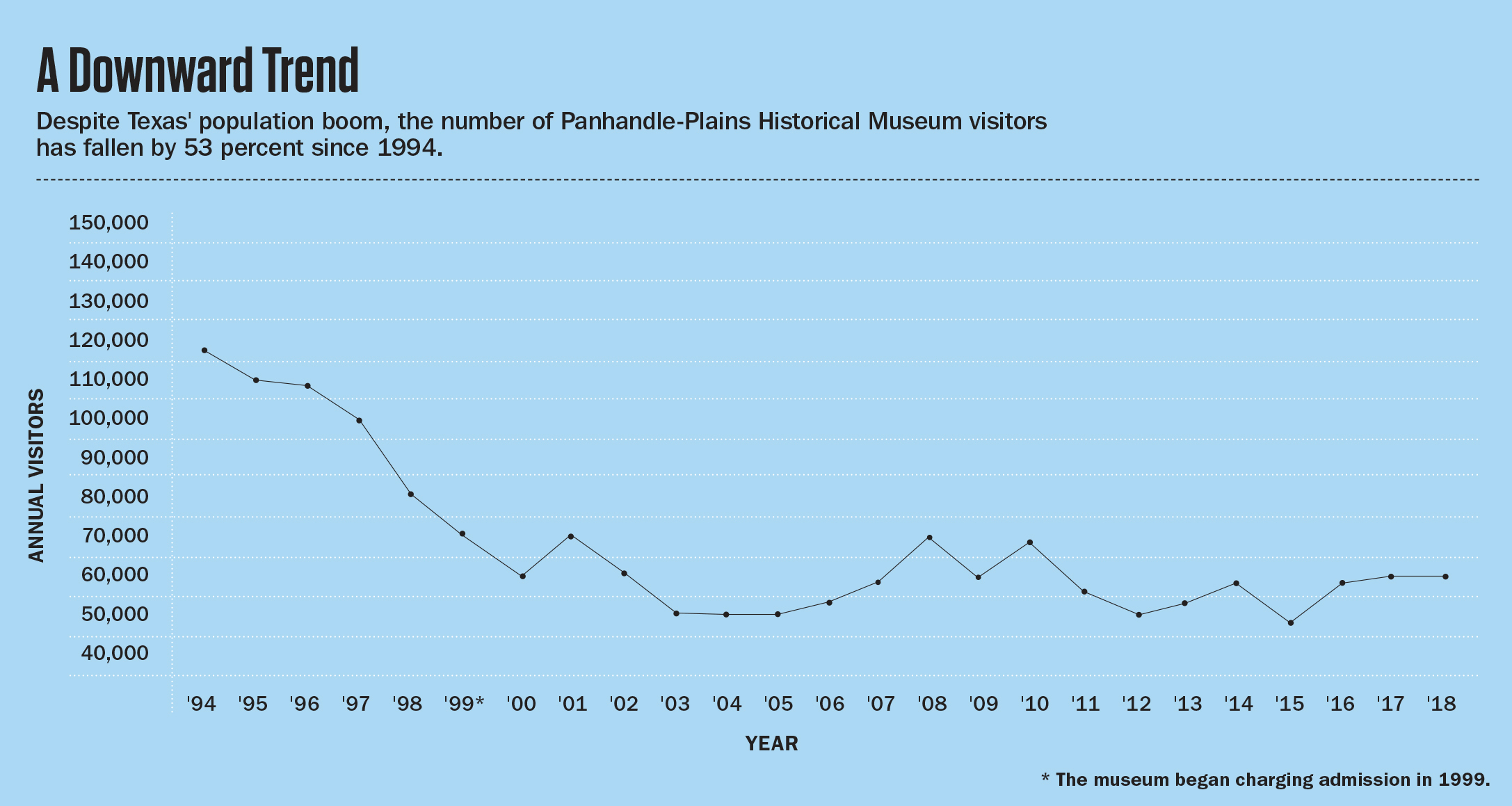

The scowl sticks when we sit down to talk at the kitchen table of the lifesize kit house. As a video loop of the seasons plays in the window — snow turning to spring wildflowers, birdsong giving way to prairie wind — Green tells me that he believes the museum is in trouble. Each legislative session brings steeper budget cuts, and staff salaries are embarrassingly low, contributing to the recent departures of several longtime curators. The building is sorely outdated, and the number of annual visitors has fallen by 53 percent since 1994. “It’s pitiful,” he says. “I don’t know what’s to become of the museum. … This place is one of the best-kept secrets in Texas.”

The secret has long been out among historians and scholars, who describe the museum as world-class. It displays valuable Plains Indians artifacts, including the headdress of Comanche leader Quanah Parker, collections of firearms and working saddles that are among the world’s largest, and work by painters Georgia O’Keeffe, Frank Reaugh and Harold Bugbee. The paleontology collection is also unparalleled; the region is so rich in fossils that a geologic time period, the Clarendonian Stage, is named in its honor (after nearby Clarendon). Even if you’ve never visited, you’ve likely seen the museum’s artifacts, which it frequently loans to other museums and documentary filmmakers across the country.

Lynn Denton, director of the public history program at Texas State University, calls the museum “phenomenal,” among other superlatives: “They have done an amazing job for almost a century and have mounted so many incredible exhibitions.” Author S.C. Gwynne, who spent a week in the archives researching his best-seller Empire of the Summer Moon, says simply, “It is my favorite single museum in the world.”

Why, then, has the museum fallen on hard times, and can it bounce back? The answer is complicated, linked to state and national political trends as well as to demographics, institutional history and management. To really understand it, you have to go back at least 85 years.

–

April 14, 1933, was a clear and sunny day in Canyon — a relief, the Canyon News reported, from the day before, which had brought “the worst sandstorm that even the old-timers had ever experienced.” More than 1,600 people gathered outside the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum to celebrate opening day. Onlookers stared in wonder at the grand Art Deco entrance, with its stone carvings of ranch brands, a Longhorn steer and the motto “Dedicated to the Pioneers.” Trumpeters played and a cannon boomed at noon as the silver doors swung open and the crowd filed in. Among them was a diminutive woman named Hattie Anderson, who had been quietly working toward this day for 12 years.

After growing up on a farm in Norborne, Missouri, as one of six children born to a pair of Swedish immigrants, Anderson did something that women of her era were not supposed to do: She earned a Ph.D. in history. Anderson came to Canyon in 1920 for a professorship at West Texas State Normal College (now West Texas A&M). She was floored to realize she’d moved to what was still, essentially, the frontier. The Panhandle was one of the last parts of Texas to be settled by Anglos; it was Comanche, Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache territory until the first white residents arrived in 1873. Many of these settlers, as well as the Native Americans whose land they’d seized, were still alive — and Anderson saw a rare opportunity. “It is possible to find living some men who have witnessed all these phases of the development of this region, from an Indian hunting ground to a farming region,” she later wrote, adding, “The stories they tell are always entertaining.”

Wanting to preserve those stories before the pioneers died, Anderson convinced 36 other professors and students to help her form a historical society, which held its first meeting in 1921. In addition to recording oral histories and publishing a scholarly journal (still in existence today), they started gathering artifacts. Among the first were “a bear foot, one leg of a billiard table used in an old saloon, an Indian skull, three arrows taken from the last Indian killed in the Panhandle, and a mount twin-head calf.” They soon ran out of space in the college’s sole building and started raising money for a museum.

Their timing couldn’t have been worse. The Great Depression hit in 1929, just as the museum effort was amping up. Crop prices in the agriculture-dependent Panhandle were at a nadir, and the region’s few wealthy donors shut their wallets. Then the devastating drought and winds of the Dust Bowl blew across the plains, and an economy already in freefall plunged even further. Unemployment soared to 25 percent. In light of this, reasonable people might have delayed or canceled a fundraising campaign, especially one for a museum rather than basic needs. Joseph Hill, president of the college and a champion of the project, wrote 25 years later that even he didn’t quite understand why they pressed on. Were they visionaries, or just foolish? “The truth is, it never seemed to occur to anyone that the organization would ever fail for want of money,” he admitted.

About $50,000 ($800,000 in today’s dollars) was needed to build the museum. In 1931, the Texas Legislature provided half of that. The rest came mostly from small donations, as Director Carol Lovelady tells me in her office. “Here’s $5, $2, $2.50, $10, $5, $3,” she says, leafing through a book that lists the founding donors. “The senior class of 1928 gave $9.90. People felt a real sense of ownership, but as time’s gone on that has faded.”

Lovelady has a ready smile, tortoiseshell glasses and a chipper personality. At one point I watch her hold the door for an elementary school class leaving the museum, thanking each child individually: “Glad you came by! Hope you had fun!” About 7,000 students visit each year, and for many in this far-flung, rural region, it’s one of the only cultural resources for miles around.

Lovelady took over leadership of the museum in 2016, after the resignation of former Director Guy “Cliff” Vanderpool. This August, the highly regarded longtime curator of art and Western heritage, Michael Grauer, took another job. It was a major loss; Lynn Denton, the public history professor, describes Grauer as having “single-handedly done some of the best scholarship there is on Texas art.” Grauer declined to speak on the record about his reasons for leaving.

In addition to Bill Green, the former history curator, four other former employees shared serious concerns about the museum’s future with the Observer. Jeff Indeck, former chief curator and archaeology curator for 15 years, said he “more than doubled” his salary when he left in 2012 for a job at the National Park Service. Others have followed his lead. There are now only 17 employees — down from a peak of 30 in 1983 — including a curatorial staff of two, plus one archivist. “The staff has been effectively gutted,” Indeck says. Asked about Vanderpool’s leadership, he says only, “Individuals can leave long legacies, and those legacies are not always good.”

“The truth is, it never seemed to occur to anyone that the organization would ever fail for want of money.”

Another former staff member, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, didn’t mince words. “[Vanderpool] pissed off the entire city of Canyon,” they said. “He did not value or believe in curators’ work” and disbanded a popular volunteer docent program. Green told the Observer that Vanderpool, who directed the museum from 2004 to 2016, “was not a successful fundraiser here” and “was not well-liked by the staff, not well-liked by the community at all.”

Vanderpool, now director of external affairs at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, says that under his leadership the museum diversified its funding sources, completed two major gallery renovations and “expanded our membership base significantly.” The volunteer docent program ended at the volunteers’ request, he says. Asked about his fundraising record, he says, “Sometimes success means continuing to thrive in a very, very negative financial environment, and we did that.”

Lovelady echoes this. “Cliff was very well-liked. It was just time for Cliff to move on.”

She’s candid about the museum’s financial struggles. About a quarter of its $2 million annual budget comes from the state, and in 2017 the Legislature slashed its annual contribution, already a modest $376,000, by 30 percent. “The relationship between the museum and the state has always done this” — Lovelady roller-coasters her hand up and down — “and right now it’s at the bottom.” Staff salaries are her biggest worry, she says, followed by facilities so outdated they pose a safety hazard: “Did you read about that museum in Brazil that burned down? That could be us.” Lovelady is aggressively courting philanthropists and foundations — “I’ve got a list of folks to call right now” — though donors tend to prefer funding shiny new initiatives and exhibits, not core expenses like salaries.

In the past, Lovelady says, the museum wasn’t “proactive” about outreach. Now it advertises a busy schedule of community events: a Night at the Museum series, yoga on the lawn, a “Dino Days” event that drew 1,300 people, a popular Dia de los Muertos celebration, trivia and movie nights, even fraternity and sorority parties. “More and more, the community and the university are looking to us as a gathering place,” says Stephanie Price, the museum’s marketing director, “and that’s what we want.”

–

All those events, though, take time and money, and money is dependent on donors and the Legislature. Many of Texas’ museums are part of public universities, which have suffered from a drastic reduction in state funding over the decades. Texas isn’t alone in that — nationwide, state funding for public colleges in 2017 was $9 billion less than in 2008. And as universities have had to tighten their budgets, they’ve focused on their core mission of teaching and research, especially in science, technology, engineering and math. Museums, often seen as islands adrift in the campus ecosystem, have been a quiet casualty of this trend.

One cautionary tale comes from the Texas Memorial Museum at the University of Texas at Austin. The natural history museum was gutted by a massive funding cut in 2013. The university’s College of Natural Sciences, faced with its own budget shortfall, eliminated its entire contribution to the museum, which today limps along with only three full-time employees, down from about 20 in 2012. “Right now our struggle is keeping the door open,” says Director Ed Theriot, explaining that he had to eliminate many programs. “The public outreach component is just gone.”

The slow-moving nature of this crisis makes it easy to ignore, and so too, perhaps, does the ability of battle-weary museum professionals to simply tune out the financials and focus on doing more with less. After all, the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum has survived lean times before. As Garry Nall wrote in a 1996 history of the museum, “Ever since its establishment … the organization has moved from crisis to crisis.” In 1941, scrambling to finance a much-needed expansion, the museum staged a brick drive as a publicity stunt, calling on thousands of Panhandle schoolkids to haul in the bricks for the new walls. In 1987, Governor Bill Clements vetoed the museum’s state appropriation of $459,000 (about $1 million in 2018 dollars); lawmakers later restored some of that money, though the 2019 amount is the lowest ever at $267,000. “I’m not saying we don’t have support, but we need a champion,” says Bill Green. “That’s what it’s going to take. A champion in Austin, plus the backing of legislators and the A&M system.”

Theriot — a biology professor who directs the Texas Memorial Museum as an unpaid volunteer — argues that while museums may seem tangential to a university’s mission, they perform crucial functions: transmitting knowledge to the public, hosting visiting scholars and researchers, educating K-12 students, training future teachers. “If you boil a university down to its absolute essence,” he says, “it’s a learned person on one side of a campfire helping others on the other side become more learned. Everything builds out from there. And museums are a big part of that.”

On my last night in the Panhandle, I drove from the museum to Palo Duro Canyon, the second-largest canyon in the United States. On the 15-minute trip just before sunset, I saw only one other car, no people, not even a cow — only acres of rolling grassland beneath a sky that seemingly went on forever. It was eerily quiet, as it had been earlier that day when, standing in the petroleum exhibit and hearing only the rhythmic hum of a pumpjack display, I realized I hadn’t encountered another museum visitor for nearly 20 minutes. Only 2 percent of Texans live in the Panhandle, and Canyon is a long day’s drive from the population centers of Houston, Dallas, Austin and San Antonio. But Palo Duro Canyon State Park draws 400,000 visitors each year, an order of magnitude more than the museum’s 55,000.

Out of nowhere, the canyon appeared: red sandstone hoodoos and vivid bands of orange and yellow shale. The colors almost seemed to glow, just as they had when I’d stood in the museum before the Georgia O’Keeffe painting “Red Landscape,” which O’Keeffe completed during her two years teaching in Canyon. In 2016, then-curator Michael Grauer discovered and reintroduced to the world another O’Keeffe painting long thought to have been destroyed. Now that Grauer and others have left, and the remaining staff is stretched thinner and thinner, how many other treasures will be lost to history?

I parked the car and walked out to an overlook, where I was surprised to find a woman standing at an easel, using pastels to sketch the last of the day’s light falling on the canyon walls. “It’s spectacular, isn’t it?” I said, idiotically. “It really is,” she replied, adding that she was on a road trip with a friend. She hadn’t heard of the museum, though when I described it she said maybe they’d stop by tomorrow: “Why didn’t I know all this was out here?”