This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

Downtown Port Arthur has the feel of a ghost town, until you look to the horizon.

Boarded-up buildings stand next to vacant lots, like missing teeth in a smile that faded decades ago. There are few people on the sidewalks, and 10 minutes can pass before a single car drives by on Proctor Street, where parades once drew crowds celebrating a float boasting, “Port Arthur Oils The World.”

Looking west, however, the signs of economic life come in the form of billowing steam and toxic fossil fuel emissions rising from stacks of the largest oil refinery in North America. The sprawling Motiva plant—a subsidiary of Saudi Aramco and one of three refineries in Port Arthur—is among dozens of industrial plants in a robust southeast Texas swath of the nation’s Gulf Coast petrochemical hub.

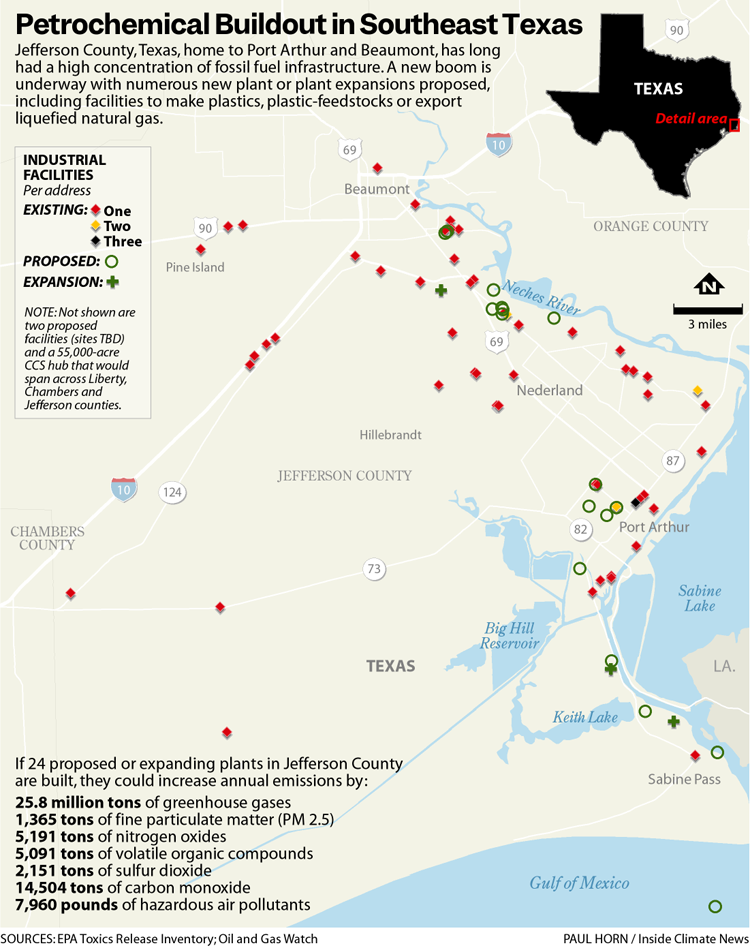

With the United States leading the world in oil and gas production, it’s boom time for the fossil fuel economy in Jefferson County. Local companies are expanding production and building new plants to make plastics, plastic feedstocks and liquified natural gas for export.

But 30 years after President Bill Clinton signed the nation’s first presidential executive order on environmental justice, the economic disparity between billions of dollars of industrial investment along the Gulf Coast and the grinding poverty of mostly Black and brown Port Arthur have renewed calls locally for fairness, equity—and justice.

Clinton’s action on Feb. 11, 1994, was a landmark declaration. For the first time, a president directed all federal agencies to address disproportionate health and environmental effects on minority and low-income populations—and develop a strategy for environmental justice.

But the movement Clinton’s order helped catalyze has struggled without significant federal funding over the three intervening decades. That finally changed under the Biden administration with passage of major infrastructure legislation in 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act the following year.

Port Arthur and its sister city, Beaumont, home to a giant ExxonMobil refinery, demonstrate just how far the United States still has to go to address the disproportionate environmental and health impacts communities of color and low-income neighborhoods have borne for more than a century since the nearby gusher wells at Spindletop ushered in the modern petroleum industry in 1901 and changed southeast Texas forever.

“That dream has been deferred for us,” said John Beard Jr., a former Port Arthur city councilman and retired ExxonMobil Beaumont refinery worker-turned environmental justice advocate who is challenging the fossil fuel industry locally and at United Nations climate and plastics summits. “We’ve got to have a clean, safe environment for ourselves and for our children.”

The signing of Executive Order 12898

From his office at the Bullard Center for Environmental & Climate Justice at Texas Southern University in Houston, Robert Bullard well remembers the cold, snowy day 30 years ago when he was summoned from a conference in Virginia to go to the White House. He and others had been pressing Congress for an environmental justice law, something with teeth and funding.

“Now, we didn’t know what the hell it was, but we got the call, and some of us went over,” said Bullard, a professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern who is now often described as the “father” of the environmental justice movement. “And they told us that this was an event that we needed to be really excited about and that something was going to be a big surprise.”

They then learned Clinton would be signing Executive Order No. 12898, the first such presidential document on “environmental justice.” Among other provisions, it tasked the government with collecting, maintaining and analyzing information comparing environmental and human health risks in people by race and income, and using that information to determine whether their programs or policies were having a disproportionately high and adverse effect on minority and low-income populations.

“It was exciting,” Bullard said. “We got a chance to go inside of the Oval Office and to witness the signing. This was the first time that environmental justice had reached the White House. It meant that the president put his pen to paper with his executive order, and there had never been an executive order like this.”

The EPA, in a statement, said Clinton’s executive order “has made environmental justice and equity an important element in a multitude of public policy arenas, including health, climate, transportation, housing, infrastructure development, and land use planning.” The order also served as a “template” for states, the EPA said. “Today, virtually every state in the nation has a statute, policy or program associated with environmental justice.”

To be sure, the order didn’t rise out of thin air. Its issuance came more than a decade after a protest in 1982 that’s often cited as the start of the environmental justice movement: weeks of demonstrations and hundreds of arrests in predominantly Black Warren County, North Carolina, where demonstrators tried to stop the dumping of toxic soil at a landfill. It was there that the Rev. Benjamin Chavis Jr., who helped organize the demonstration, popularized the term environmental racism.

The nascent movement produced a series of gains that eventually led Clinton to act. But what followed the issuance of his order has been three more decades of struggle, with relatively little money put toward the effort until recently. The challenges were greatest in former Confederate states that also resisted civil rights, said Bullard, who pioneered research into the links between race and exposure to pollution.

“It was called an unfunded mandate,” Bullard added. “In some states and (EPA) regions … it was almost at the whim of good actors, or people who wanted to do the right thing.”

Yet the executive order quickly began to empower communities of color, giving them a bigger voice to at least question the siting of industrial developments in minority communities, or excessive pollution at existing plants.

“In a lot of ways, the executive order provided a framework for communities to challenge (industrial) permits and to challenge the way that policies were being pushed forward,” Bullard said.

Ilan Levin, an attorney with the Environmental Integrity Project who represents Beard’s Port Arthur Community Action Network, said Clinton’s order has been “helpful in the court of public opinion, to have the stamp of the federal government’s approval on just the notion of the concept of environmental justice.”

It can prompt regulatory agencies “to pause or take a harder look” at some projects during the permitting or enforcement actions, he said.

“But as a matter of law,” he said, the Clinton executive order did very little. “There’s really nothing more that (companies) need to do to be able to build these big chemical plants or refineries or what have you,” Levin said. “There’s no extra (legal) requirement because of being in an environmental justice community.”

He knows what he’s talking about, having recently been part of a legal team that persuaded a federal appeals court to block a permit for Sempra to build its massive, $13 billion Port Arthur LNG export terminal.

Even with Clinton’s order, said Jeff Holmstead, who ran the EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation under President George W. Bush, the federal government has had a hard time figuring out how to integrate environmental justice into its operations. In part, he said, that’s because the Clean Air Act was written to protect all Americans equally.

But, he acknowledges, the Clinton order served to introduce the concept of environmental justice more broadly across the government and country. “More than anything else, I think it just introduced and gave visibility to an issue that really had been a very niche issue before,” said Holmstead, an energy lobbyist and lawyer with the firm Bracewell LLP.

Biden’s update, with funding

More recently, actions the Biden administration has taken to advance environmental justice eclipse those of previous administrations, providing the first significant national investment in a federal government legacy begun in important ways by the Clinton order.

On his eighth day in office, Biden issued an executive order on “Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad” that mentioned environmental justice 24 times and set forth his Justice40 initiative. It directs federal agencies to align their funding related to environmental cleanup, clean energy and climate mitigation so that at least 40 percent of the overall benefits goes to disadvantaged communities.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 also contained tens of billions of dollars for environmental justice or related concerns.

In December, the EPA announced that Bullard’s Center for Environmental & Climate Justice was one of 11 regional centers that would help distribute money from the Inflation Reduction Act to smaller environmental justice groups that typically have trouble navigating a rigorous federal grant making process. The center’s $50 million appropriation came from $600 million in the Inflation Reduction Act earmarked for the EPA’s Environmental Justice Thriving Communities Grantmaking program, which seeks to help environmental justice communities make improvements and reduce pollution.

“The executive order that Clinton signed, there was not a nickel,” Bullard said. “This one has money. It has the kind of framework to make sure the EPA is pushing out resources, streamlining, making monies available in a way that’s never been available for communities when it comes to transitioning and legacy pollution.”

Last year, Biden signed another executive order, updating Clinton’s, declaring “we have more work to do to make environmental justice a reality for our Nation, both for today and for the generations that will follow us.”

In a response to written questions, the EPA said Biden’s updated order makes sure the agency uses new scientific knowledge on cumulative environmental and climate impacts, and makes it “clear” that there be “meaningful engagement” with the public while providing “technical assistance whenever practicable and appropriate.”

Sister cities in decline

Twenty miles apart, Port Arthur and Beaumont are connected by a plethora of petrochemical pipelines, railroad tracks for moving tanks of chemicals and the Sabine-Neches Waterway, or ship channel, generating $10 billion in economic impact. But for environmental justice leaders in the two communities, money from Biden’s EJ initiatives can’t come quickly enough.

Inside Kelley’s Kitchen, a Port Arthur restaurant now used for private and community events, Hilton Kelley takes a seat with leftover “2024” New Year’s balloons floating behind him and party favors left on tables. Kelley was raised not far from here, then left for 20 years, serving in the Navy and working as an actor in California.

As a child, he said, “we used to look out the window and see all the lights (at the refinery) and say, ‘Wow, that looks like New York, and all we knew of New York was what we saw on Humphrey Bogart movies.’”

When he returned home in 2000, Kelley said he found his city and its West Side neighborhood in sharp decline and decided to stay and do something about it. Mentored by ministers and environmental justice advocates who pioneered the use of community air monitoring, he quickly found his calling as an advocate in Port Arthur and along the Gulf Coast.

In 2011, he was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize, a prestigious recognition of grassroots activists globally.

Air samples were collected in buckets as part of a citizen-empowered “bucket brigade,” and “proved our point that we had an issue,” including elevated levels of benzene, sulfur dioxide and particulate matter, he said. Motiva, the Aramco subsidiary, eventually had to implement additional pollution controls.

Among his accomplishments were negotiating a “good neighbor” agreement with Motiva that provided health coverage for the residents of the West Side for three years and established a $3.5 million fund to help entrepreneurs launch new businesses in the community. He also led a campaign that blocked Veolia Corporation from importing more than 20,000 tons of toxic PCBs, man-made chemicals banned from production in the United States in 1979, from Mexico for incineration at its Port Arthur plant.

Clinton’s executive order helped with all that, Kelley said. It was “a major, major assistance to getting stuff done. A lot of freedoms that we enjoy when it comes to free speech and fighting for environmental justice didn’t exist prior to that,” he said.

But today, it’s hard to see all of the wealth generated in the region by the oil and gas industry reflected in Port Arthur, which has been on the decline for decades, or in Beaumont, another Jefferson County community losing population.

“My advocacy is not against the petrochemical industry,” explained Christopher Jones, a disabled veteran who is acting president of Beaumont’s South End Charlton-Pollard Greater Historic Community Association, over a cup of tea at a Starbucks in the shadow of the ExxonMobil refinery.

What he wants, he said, is a good industrial neighbor, and to live in a city that works to solve its many problems.

“My plight is not being able to sit on my porch or in my yard and breathe fresh air,” he said. “To go to my tub, take a shower, in very clean water. It’s also about the sewage that runs out onto our street. There is no proper cleanup, none whatsoever.”

Driving through the streets of his neighborhood near the ExxonMobil refinery, a rotten egg smell wafts through the window of his Dodge SUV. “You have to understand, it’s better than it was back in the day,” he said, but wonders why the refinery’s flares, designed to relieve pressure during less-than-optimal operating conditions, sometimes burn “days on days, back to back,” shooting flames and black smoke into the air.

Jefferson County is considered in compliance with clean-air limits on lung-irritating ground-level ozone and particulates.

But the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory identifies 60 companies in Jefferson County that emit or discharge large enough quantities of pollutants that they must report them to the federal agency—nearly 15 million pounds in 2022, in the top 11 percent of all U.S. counties.

Jefferson County ranked third in the country for releases of 1,3-butadiene and seventh for benzene, both known as human carcinogens. It ranked first for releases of ethylene oxide, another cancer agent that the EPA began to crack down on nationally just last year, after two decades.

The EPA’s environmental justice screening tool, EJ Screen, places the cancer risk in Beaumont and Port Arthur from hazardous air pollutants in the 95th to 100th percentile, the highest in the country.

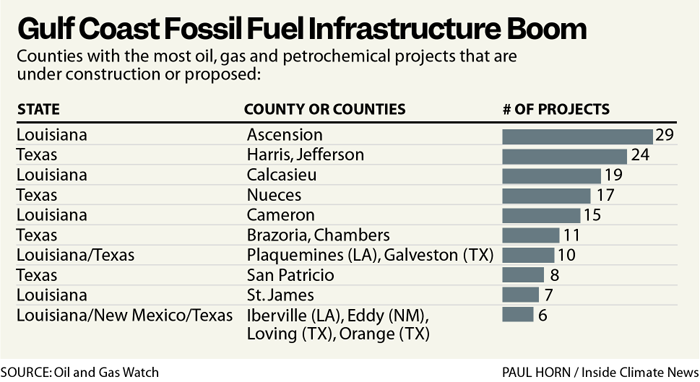

Against that backdrop is the area’s share of an ongoing petrochemical construction boom fueled by an industry awash in oil and gas.

Oil and Gas Watch, a project of the Environmental Integrity Project, counts 24 new proposed oil and gas projects or expansions for the county—tied for second most in the nation with Houston’s Harris County.

Together, the 24 projects will add as much as 26 million pounds of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, and thousands of tons of other harmful air pollutants.

If the emissions aren’t enough to contend with, southeast Texas has also taken a series of direct or indirect hits in the last two decades from powerful hurricanes or tropical storms that scientists say are intensifying faster, dropping more rain and becoming more dangerous with climate change—which is driven by carbon emissions from the region’s robust fossil fuel economy.

The hurricanes include Rita (2005), Ike (2008), Harvey (2017), Imelda (2019) and Laura and Delta, six weeks apart in 2020. Harvey dumped more than 65 inches of rain in the Port Arthur area, flooding the low-lying city and damaging or destroying more than 80 percent of its homes.

“It’s just a dramatic kind of place to understand what we are going to do in the future with all this industry, this valuable industry sitting on the coast,” said Michelle Annette Meyer, director of the Hazard Reduction & Recovery Center at Texas A&M University.

Meyer participates in a five-year, $66 million U.S. Energy Department-funded study focused in part on Port Arthur and Beaumont, that seeks to help cities mitigate the multiple effects of climate change.

“Speaking with the community, they talk about being a sacrifice zone, a place that puts out all this product that the rest of the country and world need, but they are taking on the burdens of that industry to their health to their economic livelihoods,” she said.

The natural and technological risks standout among cities in the United States, she said. “I would say Beaumont and Port Arthur are among the worst that I’ve seen in terms of these challenges.”

Still seeking justice

Looking to the future, Hilton Kelley said he welcomes the Biden administration’s environmental justice push, with major funding to potentially help the group he leads, Community In-Power And Development Association Inc., and others working to help improve local neighborhoods.

“It’s about building resiliency, with climate change impacts such as flooding and strong winds from hurricanes,” with money for “environmental justice groups that are working to help sustain the communities where we live on the Gulf Coast,” Kelley said. “And there’s money for those who are fighting pipelines, and money for those that are fighting to reduce emissions as well.”

EPA officials said they’re aware of Port Arthur area residents’ concerns and are planning to deploy additional air monitoring in the area. They also cited several recent enforcement actions against local industrial facilities.

Despite the pollution, Pat Avery, the recently retired president and chief executive officer of the Port Arthur Greater Chamber of Commerce, said many residents have a deep attachment to the fossil fuel industry and the city. Plants in her community would conduct yearly public opinion surveys, she said, and found most residents were “happy the plants are there.”

In a decades-long career in the petrochemical industry, which included working in human resources at the TotalEnergies refinery in Port Arthur, she said company managers were always well-intentioned.

“I never met management or people that I thought were deliberately trying to hurt the community,” she said, adding the industry has improved its performance over the years.

Further, Avery predicted an economic recovery for downtown Port Arthur because Motiva bought two large buildings and is renovating them. “The city is going to go crazy,” she said.

Beard, talking over restaurant servers singing “Happy Birthday” to customers at the El Viejo Tony restaurant and bar in Port Arthur, worked 37 years at the big refinery in Beaumont. But he said he came to recognize the threat a few years ago that an expanding petrochemical industry represents to the world, from climate change, and locally, from damage to the health of people and their neighborhoods.

Aboard a bus on a late January tour of industrial sites for a briefing hosted by his organization and the environmental group Beyond Plastics, Beard spoke of the dangers of the region’s many petrochemical pipelines and the occasional dramatic explosions. Five years ago, a series of blasts and a fire shot parts of the TPC Port Neches petrochemical plant high into the air, prompting a four-mile evacuation zone. “Safety is not always number one,” Beard said.

Decades now into the movement, real gains in environmental justice must include repairing the damage fossil fuel industries have left behind, he said.

“They have to apply it in ways that address the community issues and problems such as economic disparity, such as poor housing, a lack of opportunities,” he said. “You have to put money into things that are going to undo that damage.”