Problems Hide in Plain Sight at Texas’ Youth Lockups

Critics say Texas’ five remaining juvenile prisons not only fail to rehabilitate young people but “actually make them worse.”

A version of this story ran in the February 2018 issue.

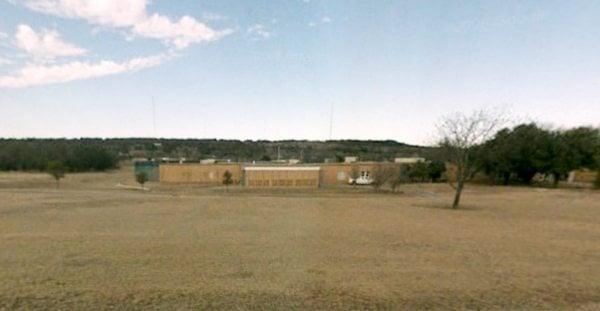

It was spring break 2017 at the McLennan County State Juvenile Correctional Facility, and the young inmates were more restless than normal. Some of the teens roamed the lockup, located about 20 miles east of Waco, throwing garbage, flashing gang signs and threatening others “with little to no redirection from staff,” according to an investigator who visited the facility in March 2017 and later wrote up her firsthand observations in an ombudsman’s report obtained by the Observer.

At one point, inmates beat another kid so badly he ended up hospitalized, all while an oblivious guard sat nearby with his back turned. The account is one of dozens produced by the Texas Juvenile Justice Department’s (TJJD) ombudsman’s office over the last two years that show persistent problems hiding in plain sight at the state’s five juvenile prisons, where Texas sends juveniles who have committed serious or violent offenses.

Staff shortages have led to canceled or truncated counseling sessions with young offenders, who complain that they don’t get enough time with case managers, who in turn complain that they’re overworked. Youth offenders across the system complain of extortion, harassment or assault by other inmates. At the Gainesville State School, youth have even accused guards of putting out “hits” on young inmates.

To Debbie Unruh, the agency’s ombudsman, the reports show a lack of rehabilitation at the youth lockups. “Whatever happens next, the focus has got to be more therapeutic,” Unruh told the Observer.

The reports, which were obtained under state open records law, also indicate that a recent high-profile scandal at the Gainesville facility may be only one example of widespread problems. In December, Governor Greg Abbott ordered the Texas Rangers to investigate all of Texas’ youth lockups, after the Dallas Morning News reported on a recent wave of staff members accused of sexual misconduct with inmates, including a guard who reportedly shared porn with youth offenders and another who was impregnated by a juvenile inmate.

Civil rights groups want Gainesville to be the catalyst for Texas lawmakers to finish the job they started in 2007, when sex abuse by juvenile prison staff at a now-shuttered lockup in the West Texas town of Pyote led to the closure of the Texas Youth Commission and prompted the creation of the ombudsman’s office.

In a November letter, child and civil rights advocates urged lawmakers to close the state’s remaining juvenile prisons — all of which are located in far-flung parts of Texas — and relocate the 1,000 or so inmates to smaller treatment centers closer to the state’s urban hubs. The facilities, they wrote, not only fail to rehabilitate young people but “actually make them worse.”

Ombudsman reports from the Evins Regional Juvenile Center in Edinburg for the past two years show detention staff struggling to provide youth the required level of therapy amid chronic turnover. One October 2016 report notes that some group sessions “were either not being held or were held for only 10 to 15 minutes.” The same report called the environment at the lockup “unstructured and unsafe,” where young, bored offenders spent much of their time lounging around the dorms, playing cards or watching TV.

“The lack of a structured routine for the youth while on the dorm continues to be a concern,” notes one report from February 2017. Another write-up from the summer said that case managers were so thinly spread across the South Texas campus that administrators had again reduced group therapy sessions.

In a prepared statement, TJJD told the Observer that agency administrators are “acutely aware of the challenges highlighted in the ombudsman’s reports” and have worked to improve conditions at the facilities. The agency says it investigates any allegations of misconduct flagged by the office and comes up with action plans when problems are identified by the ombudsman.

The agency also acknowledged that turnover, which was 41 percent for juvenile correctional officers in 2017, remains “unacceptably high,” and that TJJD employees routinely cite safety concerns, long hours and a disruptive work schedule as reasons for leaving. In 2017, the agency warned lawmakers that it lacks the funding to adequately hire and train staff, but says it’s offering recruitment and retention bonuses when possible. A new executive director, Camille Cain, takes the helm this week.

“It is hard to build staff skills and competencies that take months — even years — to develop when turnover is such a challenge,” the statement said.

In September, during another visit by the ombudsman’s office, school was back in session at the McLennan County facility, but some students had turned their workbooks into paper planes. Lisa Hale, a senior investigator, wrote in her report that teenagers “act like this because they have nothing to do.” She noted a recent increase in inappropriate sexual conduct among young inmates and reported that two teenagers refused to leave solitary housing out of fear for their safety. One of the teens had been there for a month and stank because he wouldn’t leave his cell, she wrote.

Hale also questioned why kids kept leaving the facility with tattoos after they’d entered lockup without any ink. “Several youth on campus were observed with facial tattoos, and one youth put three tattoos on his face during the visit,” she wrote. “How is this occurring if the youth are being properly supervised?”