Shortfall

How an obscure amendment to the state’s property tax code helps corporations leave counties—and citizens—stretched thin.

A version of this story ran in the January 2015 issue.

Sometime in 2007, David Swinford, then a Republican state representative from the Panhandle town of Dumas, decided he’d had enough.

For five years running, the largest taxpayer in his district, Valero Energy Corp., had refused to pay all the property tax due on its McKee Refinery, which it acquired from Diamond Shamrock in 2003. Each year Valero sued the Moore County Appraisal District, claiming that the refinery’s appraised value—close to $300 million by 2007—was too high. As court proceedings dragged on, the company paid taxes to the Dumas school district, hospital district, county and other local entities based on the undisputed portion of its valuation—about half what Valero owed.

Now the unpaid bills added up to $11 million, and the school board had raised taxes to cover the school district’s portion of the shortfall. “The reality was, [Valero was] paying partial payment, the next year they would file again and it just kept running,” said Swinford, who chaired the House State Affairs Committee at the time. “At some point it’s got to end and settle up.”

At the time, Valero had filed hundreds of similar lawsuits all across Texas, seeking to lower the taxable value of billions of dollars’ worth of property—from pipelines to convenience stores to huge refineries. The potential loss of tax money would be felt by public schools, hospitals, community colleges and local governments in the refinery belt of Southeast Texas, where student enrollment is heavily minority and economically disadvantaged. And it would be felt in little Moore County, population 22,000, a featureless rectangle on the High Plains that was once nearly wiped out by a grasshopper plague.

“The reality was, [Valero was] paying partial payment, the next year they would file again and it just kept running. At some point it’s got to end and settle up.”

Swinford wanted to confront Valero, and Craddick let him do it. As chairman of the State Affairs Committee, Swinford invoked a little-known rule that gave him power to compel Valero officials to testify under oath and produce any financial records the committee requested. Any of them. There would be no judge to complain to about trade secrets. The House parliamentarian drew up a subpoena, and Swinford called a hearing.

“Their president came,” he recalled. So did Valero’s lawyers. Refining is a close-mouthed business, and San Antonio-based Valero has successfully fought appraisal districts that sought its financial records in court. Its refusal to reveal income information in Moore County had stalled negotiations with the refinery for years. “They kept bringing up the judicial system. I said, ‘This is not a court, this is the Legislature.’ There wasn’t going to be a jury—just me. Long story short, I said I would take any measure I need to take” to get Valero to settle up, said Swinford.

He never used the subpoena, but it had the intended effect. In 2008, Valero agreed to a settlement, brokered by Swinford, that returned $7.5 million in back taxes to the Dumas school district and other Moore County public entities. (Company spokesman Bill Day declined to comment on the settlement.) It may have been the last dispute with a Texas appraisal district in which Valero wrote the checks instead of getting money back.

Swinford retired from the Legislature after the 2009 session, and in 2010 Valero sued the Moore County Appraisal District again. This time the settlement dropped the refinery’s $410 million assessment by almost one-third, lowering Valero’s annual tax bill by $1.8 million and making the Dumas school district refund $1.2 million to the company.

Swinford retired from the Legislature after the 2009 session, and in 2010 Valero sued the Moore County Appraisal District again. This time the settlement dropped the refinery’s $410 million assessment by almost one-third, lowering Valero’s annual tax bill by $1.8 million and making the Dumas school district refund $1.2 million to the company.

That pales in comparison to the $5 million the Texas City school district has paid Valero to settle its lawsuits, or the $32 million that Port Arthur schools are still paying back. But those places are crammed with refineries, while Moore County has only one. Valero’s property, which includes the refinery and an asphalt plant, currently makes up 17 percent of the county tax roll.

No one has built a new refinery in Texas since 1975; instead they refit older ones, as Valero did with McKee. McKee has been one of the company’s most profitable refineries, well positioned to capitalize on the glut of cheap light crude oil pouring out of West Texas—“a huge competitive advantage” for the company, Valero’s chief executive, Bill Klesse, told analysts in 2014, a year in which Valero tripled its third-quarter earnings to $1 billion.

Although property tax is not an income tax, refineries are bought and sold based largely on the income they’re expected to generate. Valero doesn’t say how much money McKee makes. But it’s now on the county tax roll for $285 million—$124 million less than the company agreed to in 2008.

The people of Moore County know the tradeoffs that come with oil refining. In 1956 a tank at McKee exploded in a giant fireball that rained burning fuel a mile away, killing 19 workers and volunteer firemen. In 2007 McKee caught fire again, critically injuring several workers and releasing toxic chlorine gas. The temporary shutdown did not slow Valero’s accelerating profit margins.

Though the nearby Swift meatpacking plant hires more people, the refinery pays a lot better. It’s the second-largest local employer, with about 480 steady jobs, and Dumas is beholden. Swinford understands all that. “By and large I never said anything negative about Valero—they’re a very good company and they’ve been good for this community,” he said. “But when a big company like that does not pay their taxes, somebody else has to.”

What Is a Refinery Worth?

At the heart of Valero’s lawsuits in Moore County was a complicated question: What is a refinery worth? For that matter, what is any property worth?

Since most litigation against appraisal districts settles out of court, juries rarely get to answer that question. But that’s what a Galveston jury did in 2013 when it lowered the tax value of Valero’s Texas City refinery from $527 million to $337 million, though Valero had agreed to the higher number only two years before. A local jury, in a town far from rich, sided with the world’s largest independent refiner in its perennial quest to drastically cut the taxes it owes to public schools and local governments.

Appraisal district officials across Texas were flabbergasted. Refineries are a complicated, opaque business, and the technical testimony took a whole mind-numbing week—“a battle of experts,” said Ken Wright, the chief appraiser for the Galveston Central Appraisal District. Yet members of the jury took only four hours to decide in Valero’s favor. It proved what every trial lawyer knows, that the battle is almost always won by the side that not only tells its story best, but has the simplest story to tell. “It’s taken me many years to figure this out,” said a rueful Wright, who is retiring this year.

The story, Valero’s whole case, depended on a one-sentence amendment to the property tax code that whisked through the Legislature in 1997. The details of how that happened are hazy—the legislator who introduced the amendment died years ago—but the man who wrote it is a respected Austin tax attorney, Jim Popp. His firm, Popp Hutcheson, has represented some of the most prominent plaintiffs in lawsuits against appraisal districts, among them Western Refining, the JW Marriott hotels, H-E-B, Walgreens, the Formula 1 racetrack in Austin and Valero.

“With the equal and uniform statute being interpreted the way it is, it’s hard to win. It’s a boxing match without any ropes.”

Popp’s amendment created an easier, cheaper way to claim unequal appraisal and gain an automatic reduction in value—so easy that it is now routinely used in tax protests and dominates big-ticket litigation. You simply select a “reasonable” number of “comparable” properties (available on the appraisal district’s website), adjust their values up or down (your house has a swimming pool, mine doesn’t) and find the median—the middle number on the list. What’s reasonable or comparable isn’t spelled out. Market value is beside the point. If your valuation is higher than the median, it gets lowered to that number. The amendment is now called the equity statute, or simply “equal and uniform,” echoing the Texas Constitution’s dictum that taxation be “equal and uniform.”

David Hugin, a Popp Hutcheson lawyer, argued the case in Galveston. Fairness was the theme: The appraisal district had wronged Valero by overvaluing its refinery, and the law showed the jury exactly how to set things right. It produced a breathtakingly simple answer to the vexing question of worth.

All the jury had to do was look at the comparables, the other two refineries in Galveston County—Marathon’s little 84,000-barrel-per-day plant, which processes only light sweet crude oil, and BP’s 451,000-barrel-per-day behemoth (now also owned by Marathon), which runs all kinds of crude oil, sprawls over 1,200 acres and is one of the largest, most complex refineries in the U.S. It had been appraised for $800 million more than the smaller refinery. “They are massively different,” said Wright. “Like comparing a corner grocery to a Kroger’s.”

There are 27 refineries in Texas, more than any other state, and no two are alike. Some convert tar to gas, some need a higher grade of crude, some make asphalt, some have more secondary conversion capacity. Under the rubric of fairness, the unequal statute flattens the differences between sophisticated industrial facilities, with the result that tax liability shrinks. “I can see equity being an appropriate concept where you have a large number of similar properties, but (refineries) are not cookie cutters,” said Gregg Davis, executive vice president of Capitol Appraisal Group, an Austin firm. “The only similarity is, the final product is gasoline. Everything else is going to be different.”

Yet the two other Galveston County refineries would determine the value of Valero’s 245,000-barrel-per-day refinery in Texas City. Since there were only two plants, there was no median, so the jury simply took Valero’s adjustments for innumerable differences between the two refineries, added the two final values, and divided the sum in half. That was the basis for the new appraised value of the Texas City refinery. Thus $189 million in taxable value fell away, and the Texas City school district and other local entities, which had already paid $5 million in a previous settlement with Valero, started scraping up another $5 million in tax refunds they now owed the company.

“With the equal and uniform statute being interpreted the way it is, it’s hard to win,” said Todd Stewart, an attorney with the Houston law firm Olson & Olson, which represents local government entities. “It’s a boxing match without any ropes.”

Discouraged by the Galveston verdict, the El Paso Central Appraisal District quickly agreed to a settlement with Western Refining that dropped its refinery’s appraised value from $745 million to $305 million, sending $11 million in property tax refunds back to the company and incensing some elected officials, who blamed the appraisal district. The lawsuits had gone on for years, and Western Refining warned it would use the equity statute just as Valero had if they went to trial, said chief appraiser Dinah Kilgore. “We just ran out of money,” she said.

In Big Spring, the Howard County Appraisal District shaved about $50 million off the appraisal notice it was going to send the Alon refinery—another Popp Hutcheson client. “When we settled in 2013, the reason was what happened in El Paso,” said chief appraiser Ronny Babcock. “That is the most agonizing thing as a chief appraiser you can fight your way through. When you’re an ant and they’re Goliath. It’s shocking, really.”

“That is the most agonizing thing as a chief appraiser you can fight your way through. When you’re an ant and they’re Goliath. It’s shocking, really.”

The market value of non-residential property is already difficult to get a handle on in Texas, one of only five states that does not require real estate sales prices to be disclosed. Companies jealously guard their financial information. Arguments over comparables are a blur of capitalization rates and intangibles and margins and triple net leases, comprehensible only to the attorneys and experts. But no matter how complex or inscrutable the business, the law now allows value to be determined with a sixth-grade math exercise: Find the median.

The 1997 equity statute and subsequent legislation that broadened its reach have effectively redefined what unequal appraisal means. No longer is it about relationships between property and market value, but between one property and another. It’s a radical departure from standard appraisal methodology, one that no other state has taken. “What this has morphed into is, just let me find examples of a few of my competitors and make my numbers look like theirs,” said Sands Stiefer, chief appraiser in Harris County.

For Wright, who has been with the Galveston Central Appraisal District since it was first formed in the early 1980s, the Valero trial was an eye-opener. In the courtroom he saw how everything—who got put on the jury, which experts made the best salesmen—came together for the side that told the most convincing story, in his words, “regardless of the facts.”

How would he do the telling? Wright pointed to the arithmetic that erased the expert appraisal the district had paid for and penciled in a new taxable value for the Texas City refinery, based on two wildly dissimilar refineries. “My story is and will be, when you look at those two comparable properties—is that possible?”

“Equal and Uniform”

Almost nobody anticipated the impact of the equity amendment back in 1997, except for Jim Popp and maybe a few other tax lawyers. Probably even they didn’t foresee the scale on which it would be used to lower taxes on some of the most valuable and profitable property in Texas, while ordinary taxpayers have watched the appraised value of their homes grow and grow. “I’m not sure they knew how brilliant they were,” said Stiefer.

They were dogged as well. Popp had tinkered with the tax code for years, partly to make it easier for property owners to protest and win their cases. Though never a paid lobbyist or a legislator, he has been a familiar figure at the Capitol since working for the short-lived State Property Tax Board in the early 1980s. These days, now that most of the old bulls in the Legislature who truly understood the convoluted workings of the property tax system are gone, lawmakers often rely on Popp to educate them, and he relies on them to sponsor the bills he drafts. By his own count, he has written hundreds of proposed amendments to the tax code.

No matter how complex or inscrutable the business, the law now allows value to be determined by a sixth-grade math exercise: Find the median.

Popp is particular about words, and it’s instructive to pay attention to his. By calling the equity statute simply “equal and uniform,” he purposefully invokes the Texas Constitution’s wording. By referring to the law as a “remedy,” he conveys the idea that property owners were not really protected from unequal appraisal until the equity statute came along, and undoing it now would imperil a constitutional right. It’s a powerful message, if not exactly plausible, since the only constitutional right that appears to be in jeopardy now is the one requiring property to be assessed in proportion to its market value. However, thanks to a pivotal Houston case—argued and won by Popp—Texas courts have held that when the two constitutional principles conflict, equal and uniform prevails.

Although homeowners can and do challenge their valuations on the basis of unequal appraisal, the greatest beneficiaries have been the owners of large commercial and industrial properties, many of whom are Popp Hutcheson’s clients. From 2011 to 2013, equity protests and litigation peeled more than $57 billion in taxable commercial and industrial value from Bexar, Dallas, Houston and Travis counties—about $1.35 billion in potential tax revenue their localities never received. That’s just in those four counties. Across the state, Valero has filed the most lawsuits, but the law has also helped lower tax bills for hotels, shopping malls, apartment complexes, office buildings, banks, drugstore chains, Costco, Target, H-E-B, AutoZone, 7-Eleven—the list is long and growing longer.

Sometimes the lawsuits leave local schools in the lurch. A year after the brand new Sandy Creek coal-fired power plant started up in McLennan County in 2013, its owners sued to lower its $885 million valuation by 70 percent. That punched a $1 million hole in the Riesel school district’s budget and leaves it holding the bag on a $25 million bond issue that Sandy Creek’s taxes were supposed to cover. When the Jefferson County Appraisal District settled two more Valero lawsuits last year, it brought to $32 million the tab owed to Valero by the Port Arthur school district, which has been too strapped for cash to replace its wheezing old bus fleet. State funding—that is, the taxpayers of Texas—reimbursed about $12 million, but $20 million is coming out of the school district’s own pocket.

Numbers such as those, say chief appraisers, are evidence of a steady erosion in the tax base, brought about by a formula for winning appeals that pushes median values down in a never-ending spiral. Advocates for business owners—a lineup of most of the state’s most powerful interest groups—say that the markdowns are merely evidence of greater fairness in taxation. To show how little the reductions matter, they cite the state comptroller’s annual property value study, which shows little change over the past decade in the apportionment of the statewide tax base among single-family residential, multifamily residential, commercial and industrial property. It’s proof, Popp said, that there’s been no shift in the tax burden to homeowners, and that any reductions in value are “not significant in the big picture.”

Yet it’s also true that the tax base is so large, approaching $2 trillion, that a few billion lost here and there won’t show up. “When you take everything to the state aggregate level everything disappears,” said Houston attorney Robert Mott, who has represented local governments in revenue collection matters for decades.

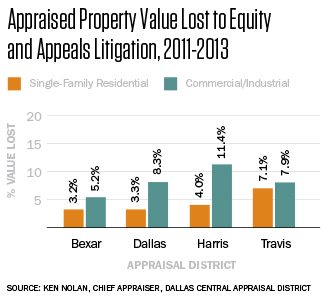

And on the local level a shift is occurring, said Dallas County chief appraiser Ken Nolan, and it tells a different story about fairness in taxation: Commercial and industrial owners are getting a substantially bigger break from equity appeals than homeowners. The numbers he gathered from four of the state’s largest counties show that appeals from 2011 to 2013 reduced commercial and industrial property values by a greater percentage than for single family residential property. In Dallas and Harris counties, it was two and a half times greater.

“The Most Unpopular People in Town”

During the coffee break at a Texas A&M workshop on property tax law in San Antonio last August, it was easy to tell the corporate executives, tax lawyers and consultants from the appraisal district folks. The former had better suits and haircuts and periodically scanned the room as they clumped together in small groups, as at a cocktail party. “Looking for business,” said a veteran attendee of these annual gatherings for property tax professionals. “They steal each other’s clients.”

Texas has more than 1,500 registered tax consultants, almost certainly more than any other state, owing much to the fact that Texans have one of the highest property tax burdens in the country. Every spring, flyers advertising consultation services hang on doorknobs like pizza coupons. One of the largest firms, O’Connor & Associates, boasts on its website that it filed more than 162,000 protests in 2013. If tax attorneys are sharks, firms such as O’Connor are whales, vacuuming up little clients—homeowners, small businesses—that might save a few hundred bucks on their tax bills.

Meanwhile appraisal districts are fending off an ever-growing number of challenges that invoke the equity statute. Ever since county appraisal districts were created in the early 1980s, following passage of property tax reform legislation, the chief appraisers have never had it particularly easy—they’re understaffed and often beleaguered, the perennial bearers of bad tidings. Rising property taxes haven’t helped. “You are the most unpopular people in town—that’s part of my opening voir dire,” said Mott.

Mott likes to say that people in the business shouldn’t take the acrimony personally, but for some it has become personal. Last February, El Paso chief appraiser Kilgore and Capitol Appraisal Group were sued by Western Refining, which challenged the firm’s $369,000 annual contract with the appraisal district and demanded a return of more than $1 million of Capitol Appraisal’s fees. The firm appraises more than half the refineries in Texas, and no one in the business can recall another such lawsuit. “They are going after us,” said Capitol Appraisal’s Davis. “We are the only appraisal firm that’s going to fight for value and not roll over. It’s very easy to split the baby and go on down the road.” In November, the El Paso appraisal district’s board ended the contract and gave the business to Wardlaw Appraisal Group of San Antonio, which has never appraised a refinery before.

“Is it nastier now? Yes,” said Drew Hahn, chief appraiser of McLennan County. “I’ve got three people in my office who were chief appraisers in other counties. Every chief appraiser that has any experience at all is trying to get out of this. And the new ones are completely overwhelmed.”

Appraisal districts are funded by school districts and other taxing entities, and except in the largest counties, their litigation budgets seldom exceed $300,000—not enough to mount a defense against a high-priced legal team. And if an appraisal district loses a case, it also has to pay the other side’s legal fees, up to $100,000. That means that when the Valero Galveston case is finally decided—it’s currently on appeal—the Galveston County Appraisal District may have to write a check to Valero for David Hugin’s fees. Salt in the wound? “Something like that,” said Wright.

Only with a lot more money can an appraisal district afford to play hardball, and that’s what’s happening in Harris County. In 2013, a sizzling real estate market produced enough sales prices for the Harris County Appraisal District to raise the valuations of all 34 Class A downtown office towers. (Class A buildings command the highest rents.) Owners of 33 buildings promptly sued. When valuations went up another 20 percent in 2014, all 34 filed suit. The appraisal district, which has been criticized in the past for undervaluing commercial property, has a $12 million budget and three law firms on retainer, and it expects to spend every penny this year defending its appraisals. “We have as strong a hand as an appraisal district can have going into this kind of litigation,” said Stiefer.

In the 17 years since its little-noticed beginning, the equity statute has gained a formidable constituency with some of the deepest pockets in Texas.

In the 17 years since its little-noticed beginning, the equity statute has gained a formidable constituency with some of the deepest pockets in Texas. As this article was going to press, business groups formed the Coalition for Equal and Uniform Taxation, circling their wagons around the equity statute and opposing mandatory disclosure of real estate sales prices, long called for by chief appraisers. In addition to the Texas Association of Business, the Texas Association of Realtors and the Texas Association of Builders, the coalition includes organizations for shopping centers, apartment complexes and hotels—all businesses that have used the statute to lower their property taxes. The Texas Association of Property Tax Professionals, a 435-member trade group, has hired the HillCo firm to defend the statute. HillCo partners Buddy Jones and Bill Miller are among the top lobbyists in Austin.

The equity statute may be a thorn in the side of the appraisal districts, but it’s also a fact of life—some now have software for use in unequal appraisal protests—and efforts to repeal it have failed miserably. The most recent casualties were bills sponsored by former state Sen. Wendy Davis (D-Fort Worth) and state Rep. Sylvester Turner (D-Houston) in 2013. Appraisers are energized this session and have some reform groups on their side, but it will be an uphill fight.

The Texas Association of Appraisal Districts has hired former state Rep. Fred Hill (R-Richardson) to work on legislation that would reconnect unequal appraisal protests to market value, and state Sen. Kirk Watson (D-Austin) is sponsoring similar legislation. “I’m not sure it’s practical to say ‘Do away with equal and uniform,’” said Watson. “We can reform the way it’s done so the public A) has a fair system and B) believes it has a fair system.” His proposal would be part of a package to include increased property tax exemptions for homeowners and mandatory disclosure of real estate sales, always a non-starter with the real estate lobby.

With the state’s Rainy Day Fund bursting with record-setting oil and gas revenues and anti-property tax sentiment at a high pitch, it is hard to imagine anyone in this Legislature facing down Valero—or any other company in Texas—with a subpoena over a disputed tax bill.

“I only heard of it being used once, and I did it,” said Swinford. “You sort of got to know where to grab people every once in a while.”