Company Town

How big business turned a Gulf Coast beach town into an industrial zone.

A version of this story ran in the June 2016 issue.

Armed with a petition, a clipboard and a blue ballpoint pen, Harold Doty set out one warm summer morning in 2013 to knock on every door in Quintana. Although there were only 66 permanent residents in this sleepy beachside town, it took Doty all weekend to make his rounds. Life in Quintana is marked by brilliant Gulf sunrises, squeaking seagulls, and neighborly conversations that unfold at a slow pace.

Doty didn’t have a hard time getting signatures on his petition. For years, folks on Quintana — 2 square miles of low dunes and sparse palm trees — had shared their island home with a small natural gas import facility owned by Freeport LNG Development, a Houston-based company. But in 2011, Freeport LNG announced that it would seek federal approval to convert its facility into a massive natural gas export plant. Once constructed, the facility would be 350 feet from Doty’s backyard and even closer to some of the other beachfront homes.

In his petition he laid out the community’s concerns: “We do not want the plant to be expanded up to our city limits creating noise above the 55 [decibel] limit outside the plant, danger to our residences from fire and explosion of the heavier than air chilling medium, or to have our beach community view devastated by having to look at more plant than beach.”

Doty, who was then on the Town Council, was optimistic. Sure, Freeport LNG was a multibillion dollar corporation, but the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) was seeking community input, and if Quintana’s residents opposed the project, perhaps the company would move its project elsewhere. Short of that, Doty thought he and his neighbors could pressure the company to build a 40-foot berm around the facility to protect them from the construction noise and the fallout from a potential explosion.

The portly, brown-haired Libertarian Party member couldn’t have predicted how swiftly the tide would turn, or have foreseen the strategies the company would employ to divide and conquer the town. First, there were carrots. Over the next two years, Freeport LNG plowed tens of thousands of dollars into the town’s coffers to placate the town’s leadership. It offered homeowners a $25,000 “inconvenience fee” per household, compensation for bearing the noise and dust from construction. When those efforts failed to win over many folks, the sticks came out: Freeport LNG pushed residents to sell their homes to the company quickly, and pledged to withhold payment until the company received approval from FERC.

Freeport LNG’s buyout strategy pitted residents who were staunch opponents of the project against those who weren’t convinced they could stop the company, or saw the situation as an opportunity to move away. The ensuing debate tore the town apart. In the spring of 2014, almost half of Quintana’s residents — many of whom had signed Doty’s petition — submitted a second petition, this time in support of the project. Within another year, the company had purchased the vast majority of the island’s 70 or so homes, tearing down many of them. As Quintana residents moved out, Freeport LNG rented the homes it had purchased to its workers. Eventually, the town elected two company employees to the five-member Town Council. Freeport LNG is currently halfway through constructing its $14 billion new plant. In a matter of two years, Quintana went from beach town to company town. Freeport LNG never built a berm.

On Quintana Island, if you face west, away from the Gulf, you’re confronted with a petrochemical skyline. Across the channel on the mainland lies the vast industrial district of Freeport, where the likes of Dow Chemical and BASF produce millions of gallons of chemicals each year that end up in everything from lozenges to carpets. But the prevailing breeze mostly blows the chemicals away from Quintana, and the concentration of industry makes for some of the cheapest living on the Texas Gulf Coast. The island is shaped like an éclair, with a single road running down the middle, splitting it into the beachfront side, where the county park and the majority of its homes are situated, and the Freeport-facing side, which has a view of large storage tanks and industrial equipment.

When Freeport LNG began constructing a natural gas import facility on the northern end of Quintana in 2005, the shale gas boom was still years off. At the time, natural gas was expensive, and a plant bringing cheap liquefied natural gas from Europe and supplying it to customers in Texas was an economically attractive proposition. Drawn by the easy access to the Gulf, millions of dollars in subsidies and low taxes, Quintana was an ideal location for a natural gas importer.

For a while, everything was rosy. The plant was almost a mile away from the nearest home, largely out of sight and out of mind. In spring 2008, a 909- foot tanker carrying the company’s first shipment docked at its berth. In the next few years, however, natural gas prices plummeted. The country was awash in cheap natural gas. Business dried up, and the billion-dollar plant sat mostly idle.

That’s when Freeport LNG considered a new plan. What if, instead of importing natural gas and selling it to customers in the United States, it reversed its operations, liquefying the cheap natural gas produced in Texas and selling it to customers in Europe and Asia, where prices were higher?

Converting the import plant to an export terminal was a massive undertaking. The project would cost $14 billion and require building three sets of liquefaction trains that could chill natural gas to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit and storage tanks the height of 15-story buildings. Still, it was an easy choice for Freeport LNG. It had already succeeded in securing permits for its import facility, making it easier to get approval for an export terminal.

In 2011, Freeport LNG quietly filed an application with FERC and held open houses, as required by law, in Quintana and nearby Oyster Creek, a town on the mainland. But when folks in Quintana learned of Freeport LNG’s plans to expand its facilities closer to their homes, many were livid. At Town Council meetings and informal gatherings, residents worried about the effect on property values, the damage an explosion at the plant could inflict on the island, and the constant noise they would have to endure during construction. The town hired a consultant to find ways to stop the project.

But the residents soon realized they had few options. In the early 2000s, when Freeport LNG was planning on constructing the import plant, it convinced the town to de-annex a portion of the northern half of Quintana. In exchange, the company pays Quintana $1.25 million a year. Now, the company could lease some of that land for its new project from port Freeport without needing to negotiate with the town. From a legal standpoint, there wasn’t much Quintana could do.

The project would cost $14 billion and require building three sets of liquefaction trains that could chill natural gas to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit and storage tanks the height of 15-story buildings.

While opponents were researching ways to block Freeport LNG, the company had already made strategic moves on the island. More than a year before it publicly announced its buyout offer, the company quietly bought all five homes on Cortez Street. According to Freeport LNG’s modeling, this street was the one place on the island where noise from construction would exceed 55 decibels, the limit set by FERC. If it didn’t secure the Cortez Street houses, its permit application would be held up and it would have been forced to either build a sound wall or engineer another solution.

Once Freeport LNG had Cortez Street under its control, it abruptly changed its strategy. It attempted one last-ditch effort to soothe residents by offering $25,000 per household. When homeowners refused the offer, Freeport LNG announced that it would buy the homes of those who didn’t want to stay. But the offers the company made were conditional. Freeport LNG would only make payments once it got the green light from FERC.

“They saw an actual possibility that they might not get the permit,” Doty said. “That’s when they started offering buyouts.”

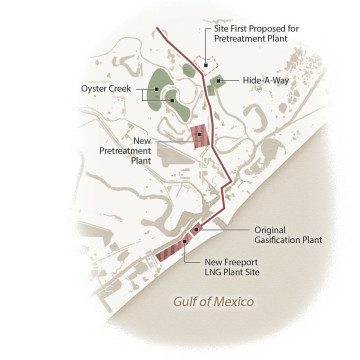

As Freeport LNG began trying to buy out Quintana, it was also dealing with another vocal group of homeowners in Oyster Creek, where it proposed locating its 189-acre pretreatment facility. Once operational, the facility would remove carbon dioxide, water vapor and other chemicals from the natural gas so it didn’t freeze when it was cooled to subzero temperatures in the liquefaction plant. Some of the chemical compounds were to be expelled into the air.

Residents of Hide-A-Way on the Gulf, a wealthy Oyster Creek neighborhood within a mile of the proposed facility, were not happy. They quickly formed a group, set up a website and actively sought media attention. They filed comments with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which would issue the facility an air permit. When Freeport LNG held open houses, Hide-A-Way protesters showed up with signs.

Worried the opposition would delay the project, Freeport LNG gave in to the demands and agreed to move the pretreatment facility a few miles east, farther away from communities.

It also offered the three women who had led the community charge an air monitor in exchange for withdrawing their request for a contested case hearing with the state environmental agency. The company agreed to build, maintain and operate an air monitor within Hide-A-Way by the end of 2016. Two of the women signed the nondisclosure agreement and are forbidden from criticizing Freeport LNG or even acknowledging the existence of the agreement.

The third, Melanie Oldham, refused.

“There were more of them out there [in Oyster Creek] and their voice was louder and better organized,” Doty, now the mayor of Quintana, reflected.

Debbie Alongis, a Quintana Town Council member, had another explanation: “When the [Oyster Creek] residents came very calmly [and] everything was presented in a well-mannered way, they succeeded. Even if [Quintana residents] did stand a chance, they ruined it themselves by their attitude and by their aggressiveness,” she said.

Freeport LNG’s community affairs director, Wendy Mazurkiewicz, said the company had made many good-faith efforts to listen to residents’ complaints and address them. She pointed to Freeport LNG’s involvement in beach cleanups and participation in the town’s yearly Mardi Gras parade as evidence that the company was interested in keeping residents happy. “From the get-go we were being a good neighbor,” she said.

“It was never our intent to push everyone out and essentially wipe out the town,” said Mazurkiewicz. “We have not discussed what would happen to the homes that we have purchased once construction is done. … We’ve talked about putting them on the market and selling them. We’ve talked about selling them at a discount to employees. We’ve had brainstorming sessions, but we’ve never had any definitive plans.”

Freeport LNG’s conditional buyout offer was a stroke of genius. No one would get the money until the plant was permitted. That put immense pressure on the protesters — then a majority of the town — to step aside. The arm-twisting and social pressure didn’t have to come from the company; the neighbors eager to cut a deal would do the work all on their own.

Among those on different sides of the issue were Wade and Linda Cook. Wade had been visiting Quintana since he was a child. After he retired from Chevron in 2009, the couple moved to Quintana permanently. Wade was among the first to sign Doty’s petition and was outspoken about his opposition to the plant, partly because it would be a few hundred feet from his backyard.

When Freeport LNG sent John Richers, a former Port Freeport commissioner, to negotiate with Wade, he refused. Wade’s adult son, Cliff, has Down syndrome and Wade had never seen him happier than when he was fishing on the pier down the street. Plus, Wade had settled in Quintana with the intention to live out the rest of his life on the island. He wasn’t about to be run off.

But Linda thought her husband was being naive. There weren’t too many eager home-buyers sniffing around Quintana; Linda thought they could get a good enough deal to buy a home closer to Houston.

Wade was facing pressure from Richers too. Richers told the Cooks that if they didn’t strike a deal by February 2014, they wouldn’t get a second opportunity to negotiate with the company. That sent the Cooks into a panic. Linda worried that if they didn’t sell in time they would be the last people on the island. In a phone conversation with the Observer, Richers denied that he made the statement about the deadline or pressured the Cooks in any other way.

“It was never our intent to push everyone out and essentially wipe out the town.”

Similar arguments played out among other families and neighbors on the island. Richers had made his rounds, and many worried the town would never be the same. They also recognized that if Freeport LNG owned the homes, it would probably rent them out to its workforce. Not many wanted to live in a town of Freeport LNG employees.

There was recent precedent for defeating a new LNG plant. Earlier this year, FERC denied a petition for an LNG plant in Oregon, citing a lack of demand for liquefied natural gas in Asia as well as adverse effects on landowners. But Freeport LNG was ahead of the curve in 2011, when it applied for its permit. Natural gas prices hadn’t reached decade lows as they did this year, and local landowner opposition, as it turned out, could be squashed.

By the end of 2013, Freeport LNG was in the thick of negotiations with Quintana residents. An air of paranoia permeated the island and rumors circulated wildly. Those who were the most vocal and adamant about staying demanded exorbitant payments for their homes. One woman erected a 10-foot sign in front of her pink beach house: “SOLD Quintana for LNG Chump Change.” There was talk that some of the council members had received bigger payouts for their homes, in part to convince the rest of the town to sell.

“In school did you ever play that game where someone told a story and you repeat it to another person and nothing is the same from one end to another?” Alongis, a 28-year resident of Quintana, said, sitting on a bench outside the town hall. “That’s kind of what happened out here. It became a feeding frenzy.”

Some of the residents who had aligned with Doty started to believe that fighting Freeport LNG was futile. Based on comments from FERC staff members, which were unfavorable to environmentalists and residents, it looked highly likely that the project would be approved. Alongis believed those who were fighting the plant were doing so in the hopes that they could get better deals.

“Even those opposed to it were good at spending that money. There was a handful, and to this day they want more and more,” said Alongis.

“In school did you ever play that game where someone told a story and you repeat it to another person and nothing is the same from one end to another? That’s kind of what happened out here. It became a feeding frenzy.”

Alongis and her husband sold three homes to Freeport LNG for what she called a “tidy profit.” Alongis says that working with Freeport LNG could have benefitted other residents too. When the company saw that the residents were fighting aggressively to stop the plant, Freeport LNG withdrew from some of its community engagement efforts, such as funding the beach cleanups, she said.

But for others in the town, Alongis’ efforts to play ball with the company were a sign that she’d sold out. Once Alongis and some of the other members on the Town Council relented, the residents who had been holding out gave in. Tired of the squabbling and aggression within the community, 36 residents filed a second petition asking the council to stop spending the town’s money on the consultant it had hired.

“Your [sic] good enough to take their money but then your Greed wants little bit more and your [sic] using the Town’s Income for your personal outcome. This must be stopped,” the petition read.

The signatories included many of the residents who had signed the anti-Freeport LNG petition. Linda Cook was among them.

As the discussion in the community reached fever pitch, Wade and Linda’s own disagreements had escalated too. Ultimately, Wade gave in, believing that if he didn’t meet Freeport LNG’s deadline he’d never have the option to sell his home again.

After he sold, Freeport LNG extended its deadline by two months. Then again by another month.

“Some of those negotiations went on all this year till about two months ago,” Cook told the Observer, sitting on his front lawn in the shade of his modest one-story stilt house. “And they got a lot more money for it. In some cases it was twice what they wanted.”

He said it’s not a case of “sour grapes.” He has a three-year lease to rent his home from Freeport LNG and is considering building another house on the island farther away from the plant.

Mazurkiewicz, the Freeport LNG community affairs director, acknowledged that the company’s decision to keep extending deadlines could have caused residents to scramble to reach an agreement.

“I see your point,” she said. “Those letters were sent by the legal department and those decisions were made by them.” Mazurkiewicz said Freeport LNG set strict deadlines because it needed to quickly figure out how much money it was on the hook for.

So far, Freeport LNG has demolished 26 homes that it purchased from Quintana residents, claiming they are uninhabitable, even though some of the houses were occupied before they were sold to Freeport LNG.

Today, the island still has some 50-odd full-time residents, but the demographics have changed dramatically. Only a handful of the original Quintana residents still reside on the island. Many of the beach homes now house Freeport LNG employees.

Linda and Wade are still married, but they live apart. Linda visits Wade in Quintana on the weekends.

“Wade and I have had our differences,” Linda said, sitting on the back of a parked golf cart in front of Wade’s house. “It’s taken life away from us and so it’s just bittersweet. It’s a town that has survived this long and when [Freeport LNG] chose to come here it was supposed to benefit Quintana.”

Last year, after two of the council members took the buyout and left town, the remaining council members, including Debbie Alongis, couldn’t agree on who they wanted to nominate to the council. When an election was held a few months later, so many of the original residents had moved away that the new town members elected employees of Freeport LNG and one of its contracting companies.

Doty says it’s yet another sign that the company has taken over Quintana. Once Freeport LNG employees occupy the majority of council seats, they will have say over how the company’s payments to the town are spent, he predicts. It will finally be the company’s town.

Just 50 miles north of Quintana, another natural gas exporter is floating a proposal for a liquified natural gas plant on Pelican Island, a small isle that hosts Texas A&M University at Galveston and is part of the city of Galveston. It is one of about two dozen LNG projects under consideration in the United States. “I hope they’re ready to fight,” Doty says.

Update, June 13: Next Decade, the energy company floating a proposal for an LNG plant on Pelican Island, withdrew its plan after it failed to reach an agreement with the Port of Houston Authority. The company is moving forward with another LNG plant near Brownsville.