Will The Reckoning Over Racist Names Include These Prisons?

Many prisons, especially in the South, are named after racist officials and former plantations.

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for The Marshall Project’s newsletter, or follow them on Facebook or Twitter.

Not long after an Alabama lawyer named John Darrington began buying up land in Southeast Texas, he sent enslaved people to work the soil. They harvested cotton and sugarcane, reaping profits for their absentee owner until he sold the place in 1848.

More than a century and a half later, men—mostly Black and brown—are still forced to work in the fields. They still harvest cotton. They still don’t get paid. And they still face punishment if they refuse to work.

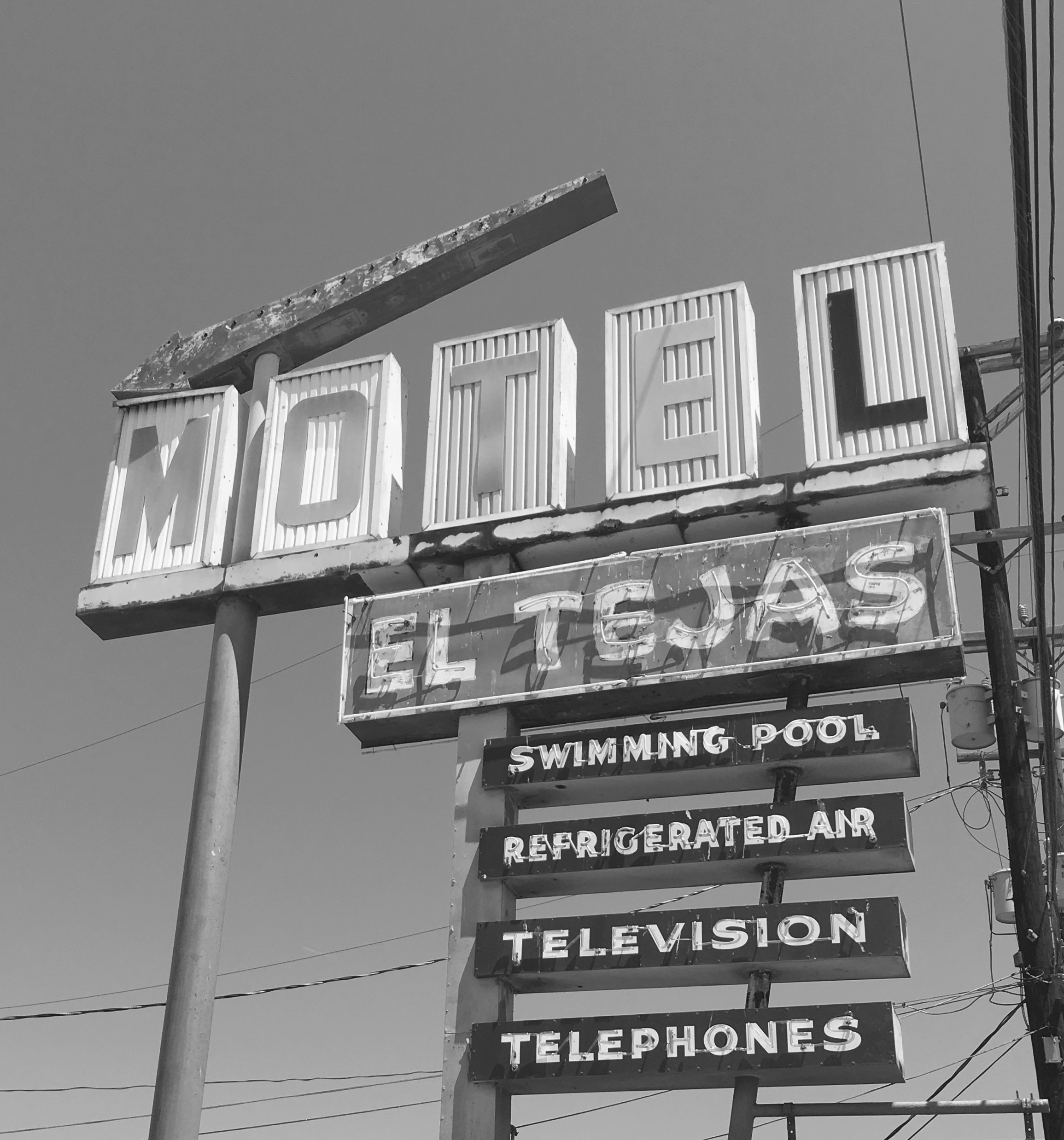

They are prisoners at the Darrington Unit, one of Texas’s 104 prisons. And not the only one in the South named after slaveholders.

While the killing of George Floyd has galvanized support for tearing down statues, renaming sports teams and otherwise removing markers of a (more) racist past, the renewed push for change hasn’t really touched the nation’s prison system. But some say it should. Across the country, dozens of prisons take their names from racists, Confederates, plantations, segregationists, and owners of slaves.

“Symbols of hate encourage hate, so it has been time to remove the celebration of figures whose fame is predicated on the pain and torture of Black people,” said DeRay McKesson, a civil rights activist and podcast host.

Some candidates for new names might be prisons on former plantations. In Arkansas, the Cummins Unit—now home to the state’s death chamber—was once known as the Cummins plantation (though it’s not clear if the namesake owned slaves). In North Carolina, Caledonia Correctional Institution is on the site of Caledonia Plantation, so named as a nostalgic homage to the Roman word for Scotland. Over the years, the land changed hands and eventually the state bought that and other nearby parcels.

“But the state opted to actually keep that name in what I would say is a kind of intentional choice,” said Elijah Gaddis, an assistant professor of history at Auburn University. “It’s so damning.”

Among several state prison systems contacted by The Marshall Project, only North Carolina’s said it’s in the early stages of historical research to see what name changes might be appropriate. Spokesman John Bull said the department is “sensitive to the cultural legacy issues sweeping the country,” but its priority now is responding to the COVID pandemic.

Two of the most infamous and brutal plantations-turned-prisons are Angola in Louisiana and Parchman in Mississippi—but those are their colloquial names; neither prison formally bears the name of the plantation that preceded it. Officially, they’re called Louisiana State Penitentiary and the Mississippi State Penitentiary.

“Symbols of hate encourage hate, so it has been time to remove the celebration of figures whose fame is predicated on the pain and torture of Black people.”

In some parts of the South, many prisons are former plantations. Unlike Darrington or Cummins, the vast majority at least bothered to change the name—but that isn’t always much of an improvement.

In Texas, for example, most of the state’s lock-ups are named after ex-prison officials and erstwhile state politicians, a group that predictably includes problematic figures. Arguably one of the worst is Thomas J. Goree, the former slave owner and Confederate captain who became one of the first superintendents of the state’s penitentiaries in the 1870s, when prison meant torture in stocks and dark cells.

“Goree was a central figure in the convict leasing system that killed thousands of people and he presided over the formal segregation of the prison system,” said Robert Perkinson, a University of Hawaii associate professor who studies crime and punishment. “Even though he thought of himself as a kind of benevolent master, he doesn’t age well at all.”

In his book Texas Tough, Perkinson describes some of the horrors of the convict leasing practices of Goree’s era. Because the plantation owners and corporations that rented prisoners did not own them, they had no incentive to keep them alive. If you killed an enslaved person, it was a financial loss; if you killed a leased convict, the state would just replace him. For decades, Texas prison laborers were routinely whipped and beaten, and the leasing system in Goree’s day sparked several scandals, including one involving torture so terrible it was known as the “Mineola Horror.” Goree defended the system: “There are, of course, many men in the penitentiary who will not be managed by kindness.” Plus, he explained, prisoners in the South needed to be treated differently because they were different from those in the north: “There, the majority of men are white.”

The present-day Goree Unit is in Huntsville, an hour’s drive north of Houston, but his family’s former plantation in Lovelady—about 20 miles further north—has been turned into another prison: The Eastham Unit, named for the later landowners who used it for convict leasing. James E. Ferguson—namesake of the notoriously violent Ferguson Unit, also near Huntsville—was a governor in the 1910s who was also an anti-Semite and at one point told the Texas Rangers he would use his pardoning power if any of them were ever charged with murder for their bloody campaigns against Mexicans, according to Monica Muñoz Martinez, historian and author of The Injustice Never Leaves You.

Ferguson got forced out of office early when he was indicted and then impeached. Afterward, he was replaced by William P. Hobby, a staunch segregationist who opposed labor rights and once defended the beating of an NAACP official visiting the state to discuss anti-lynching legislation.

Hobby, too, has a prison named after him.

“In public he tried to condemn lynchings, but then when you look at his role in suppressing anti-lynching organizing he was trying to suppress those efforts,” Martinez said of Hobby. “It’s horrific to name a prison after a person like him. It’s an act of intimidation and it’s a reminder that the state is proud of that racist tradition.”

Northwest of Abilene, the Daniel Unit takes its name from Price Daniel, a mid-20th-century governor who opposed integration, like most Texas politicians of the era. As attorney general he fought desegregating the University of Texas Law School, and later he signed the Southern Manifesto condemning the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

The namesakes of the Billy Moore Unit and the frequently-sued Wallace Pack Unit were a pair of prison officials—a major and a warden—who died in 1981 while trying to murder a Black prisoner. According to Michael Berryhill, a Texas Southern University journalism professor who wrote a book on the case, it was such a clear case of self-defense that three Texas juries decided to let the prisoner off.

“They should not have prisons named after them,” Berryhill said. He called it “a stain” on the Texas prison system’s reputation.

In Alabama, the Draper Correctional Center is named after Hamp Draper, a state prison director who also served as an interim leader—or “imperial representative”—in the Ku Klux Klan, as former University of Alabama professor Glenn Feldman noted in his 1999 book on the state’s Klan history. The prison closed for a time in 2018 then re-opened earlier this year as a quarantine site for new intakes.

In New York City, the scandal-prone Rikers Island jail is one of a few that’s actually generated calls for a name change, based on the namesake family’s ties to slavery. One member of the Dutch immigrant clan, Richard Riker, served as a criminal court judge in the early 1800s and was known as part of the “Kidnapping Club” because he so often abused the Fugitive Slave Act to send free Blacks into slavery.

To be sure, most prisons are not named for plantations, slave owners or other sundry racists and bigots—at least not directly. Most states name their prisons geographically, using cardinal directions or nearby cities.

But some of those geographic names can be problematic. In Florida, Jackson Correctional Institution shares a name with its home county. But Jackson County is named after the nation’s seventh president, Andrew Jackson, who was a slave owner obsessed with removing Native people to make room for more plantations. Less than an hour to the south, Calhoun Correctional Institution also bears the name of its county, which is in turn named after John C. Calhoun—Jackson’s rabidly pro-slavery vice president. The same is true of Georgia’s Calhoun State Prison.

Also in Georgia, Lee State Prison is in Lee County, which is named in honor of Henry Lee III, the patriarch of a slave-owning family and the father of Robert E. Lee. A little further northeast, Lee County in South Carolina—home to violence-plagued Lee Correctional Institution—is named after the Confederate general himself.

In Arkansas, the namesake of Forrest City—home to two eponymous federal prisons—is Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Grand Wizard in the Ku Klux Klan who also controlled leased convicts in the entire state of Mississippi at one point.

To many experts, the idea of changing prison names feels a bit like putting lipstick on a pig: No matter what you call it, a prison is still a prison. It still holds people who are not free. They are still disproportionately Black and brown.

“If you are talking about the inhumanity, the daily violence these prisons perform, then who these prisons are named after is useful in understanding that,” Martinez said. “But what would it do to name it after somebody inspiring? It’s still a symbol of oppression.”

But to Anthony Graves, a Texas man who spent 12 years on death row after he was wrongfully convicted of capital murder, the racist names are a “slap in the face of the justice system itself.” New names could be a powerful signal of new priorities.

“At the end of the day the mentality in these prisons is still, ‘This is my plantation and you are my slaves,’” he said. “To change that we have to start somewhere and maybe if we change the name we can start to change the culture.”

Read more from the Observer:

-

From Boom to Bloodbath: The Permian Basin’s shale revolution is over and renewable energy is surging. What does that mean for Texas’ future?

-

How COVID-19 Threatens Texas’ Restaurant Industry: The COVID-19 pandemic threatens the future of the barbecue joints, taco trucks, bánh mì shops, and country cafes that make up Texas cuisine.

-

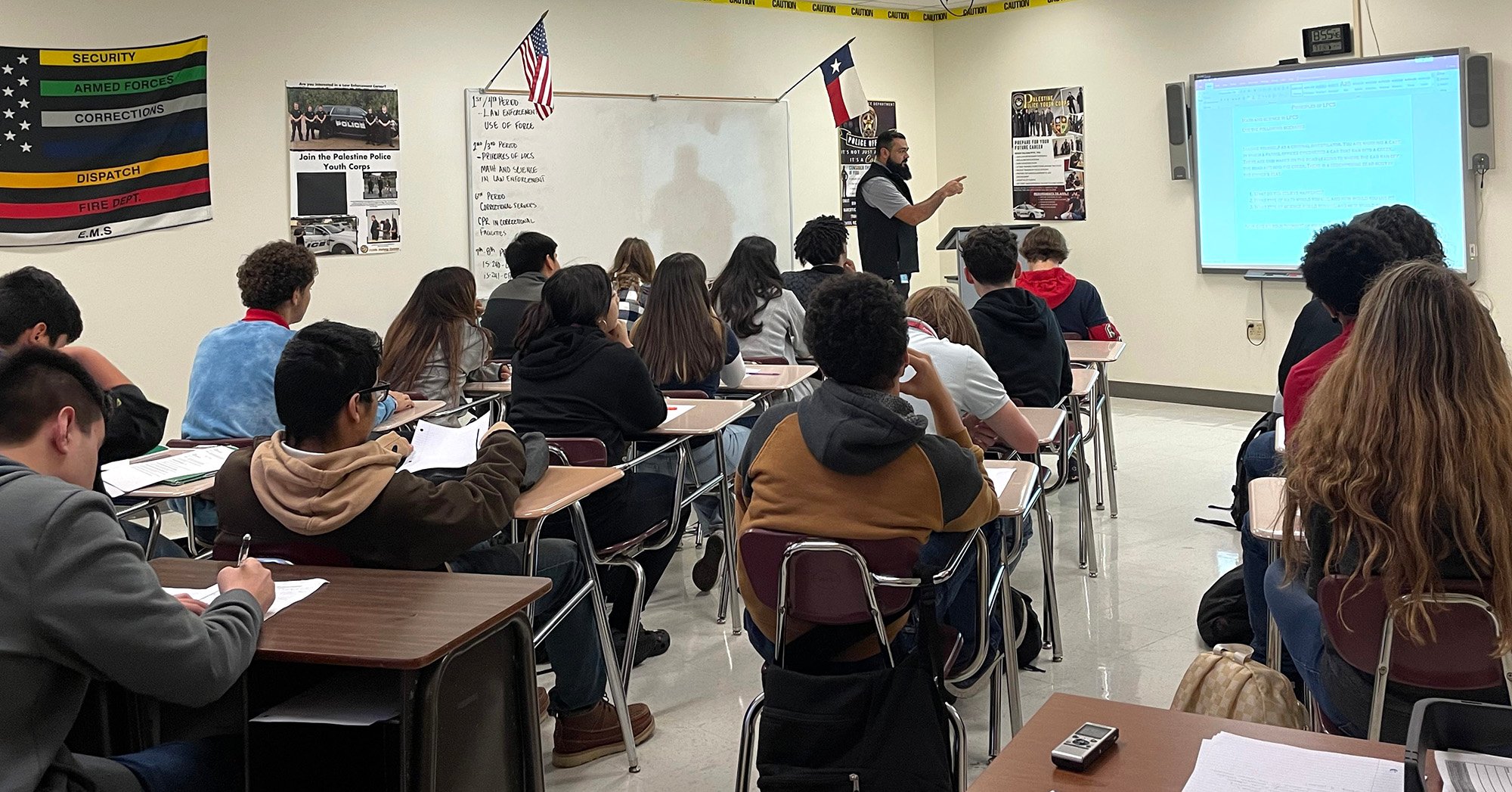

Muslim Activists Say It’s Time to Join Black Lives Matter Calls to Reform Law Enforcement: A Dallas mosque’s decision to partner with law enforcement during a nation-wide reckoning on the role of policing fits into a broader hesitation from Muslim communities to jeopardize relationships with police departments.