Fearless and Funny, Molly Ivins Comes to Life in ‘Raise Hell’

If only she were around today.

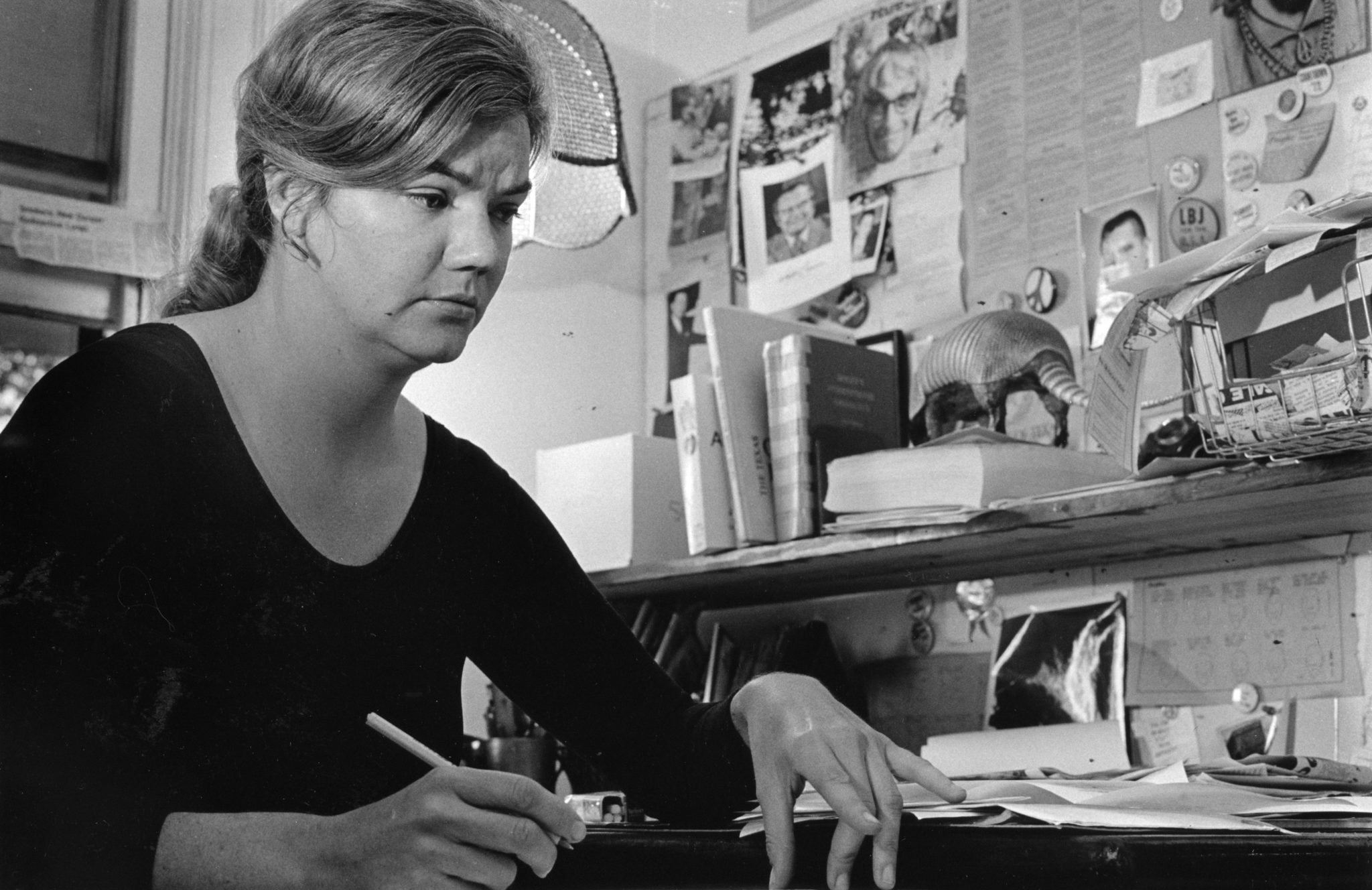

I learned within my first day at the Texas Observer that Molly Ivins looms large over this place. Literally, two sizeable black-and-white photos of her hang above the water cooler. Every time I rummage in the storage cabinet for a pen or notebook, a lifesize Ivins portrait leaning on the wall next to it seems to ask, “What are you looking at?” When I tell people I work at the Observer, they typically exclaim, “Oh, the Molly Ivins place!” Our annual journalism award and gala is called, tersely and in all caps, the MOLLY. We regularly receive requests for photos of Ivins, and even get the occasional press release addressed to “Dear Molly,” though it’s been 43 years since she worked here and 12 years since her death. Like many, I’ve read Shrub, her and Lou Dubose’s best-selling roast of George W. Bush, and seen her barbed one-liners quoted everywhere. I knew her writing was equal parts smart, funny and profane, and that no Texas commentator before or since has matched her wit. But who was she?

I had no idea, which is why I was excited to watch Raise Hell: The Life & Times of Molly Ivins, which screened at SXSW today. Janice Engel’s 90-minute movie draws on interviews with friends and colleagues, as well as big-name commentators like Dan Rather and Rachel Maddow, to paint a rich, nuanced portrait of a woman who never stopped speaking truth to power.

After reeling viewers in with a montage of some greatest hits — on Dan Quayle: “If you put that man’s brain in a bumblebee it would fly backwards” — we begin with Ivins’ difficult childhood. She grew up in Houston’s tony River Oaks neighborhood, the second of three kids. Her mother often referred to Molly as “our smart child” and her sister, Sara, as “our beautiful child.” Surpassing 6 feet by age 12 made Ivins, as one friend tells the camera, “painfully shy.” Cut to a clip of Ivins later in life, telling a room to uproarious laughter, “I felt like a Saint Bernard with a bunch of greyhounds.” The film is stuffed with moments like these, culled from interviews and speeches, and in each Ivins’ charisma is on full display. It’s impossible not to marvel at her ability to mesmerize an audience, to send people into fits of laughter with a single well-timed quip. And she wasn’t even a broadcast journalist.

Relying on the memories of a few friends, on her writing, and on archival clips in which Ivins was performing a role she’d perfected, “Raise Hell” can only get so close to the truth of who she really was, fame and accolades aside.

Ivins found solace editing the St. John’s School student newspaper, and the family wanted for nothing since her father, a conservative oil executive, pulled a hefty paycheck. But he was an angry drunk, and as her siblings recount in the film, after cocktail hour the fighting would start. Molly regularly got into shouting matches with her dad, especially when she dared to bring an African-American friend over to visit. Escaping to Smith College in Massachusetts was a relief; she studied abroad in Paris and immersed herself in books. There, and in her first reporting jobs at the Houston Chronicle and the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, she spoke in a style one friend compares to that of Jackie Kennedy. That’s notable because as Ivins rose to fame later in life, she cultivated a folksy Texan persona complete with cowboy boots, a black lab named Shit and a twang. It wasn’t exactly fake — she was clearly in her element when driving her pickup or sitting around a campfire with a beer — but it was a calculated performance.

Speaking of beer, the film doesn’t shy away from Ivins’ lifelong struggle with alcoholism. She brought a six-pack to her job interview at the Observer and spent countless hours carousing at Scholz Garten, a downtown watering hole frequented by progressives. Alcohol was also a writing crutch: As Observer co-editor Kaye Northcott recounts, Ivins worried she wouldn’t be funny sober. Eventually, close friend and former Texas Governor Ann Richards had to stage an intervention — a process with which Richards was familiar, having had one herself. Confronting her demons while also undergoing treatment for breast cancer brought Ivins close to what she described as “the final fuck-it” (presumably suicide, which claimed her father in 1998).

Here, the limits of a posthumous documentary present themselves. Relying on the memories of a few friends, on her writing and on archival clips in which Ivins was playing a role she’d perfected, Raise Hell can only get so close to the truth of who she really was, fame and accolades aside. Aside from her drinking, the film touches very briefly on Ivins’ private life, and suggests she was just that — private. She had a wide circle of friends but few confidantes, and always lived alone. Her brother, Andy, chokes up while remembering how they connected only near the end of her life: “I realized, son of a bitch, I should’ve been doing this a long time before.”

Instead, the Ivins who feels most alive in the film is the same one we’ve all known and loved for decades, the one who once declared of a Republican Congressman, “If his IQ slips any lower, we’ll have to water him twice a day.” After that line appeared in a particularly salty column, the Dallas Times Herald posted billboards across the city asking, “Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She?” Though her columns often resulted in threats and hate mail, they were picked up by 400 newspapers. Today, as the press mobilizes against Trump’s attacks on the Fourth Estate, her thoughts on “fairness” in journalism seem prescient: “There’s no such thing as objectivity and everybody in journalism knows it. So my solution has been to let my readers know where I stand, and they can take that with a grain of salt or a pound of salt, depending on their preferences.”

It’s a common lament: If only Molly Ivins were alive to help us survive Trump. What fun she would have with his petulant tweets, his orange pallor and toddler’s attention span! The closest thing to her blend of humor and truth, maybe, exists in the work of comedian-hosts like John Oliver and Samantha Bee, and in the shrinking pages of alt-weeklies. And, of course, we try to carry on her legacy at the Observer, where we still believe journalists can “raise hell, have fun and keep learning.”