Raising the Bars

What's next for Texas criminal justice reform?

A version of this story ran in the March 2016 issue.

Long considered perhaps the toughest of tough-on-crime states, Texas finds itself in 2016 in a remarkable position: An increasingly strong bipartisan coalition is pushing for reforms to the criminal justice system. On the agenda are changes that would have been unthinkable back when Democratic Governor Ann Richards led the charge to triple the size of the state’s prison system, touting prisons as rural economic development.

Though Texas still has the most prisoners of any state, in recent years it has reduced its incarceration rate and closed three prisons — the first time that’s happened, ever. Meanwhile, the Legislature enacted significant reforms to prevent, discover and redress wrongful convictions, and the state has become a national leader on forensic-science reform.

During the most recent legislative session, legislators decriminalized truancy for juveniles, ended the pick-a-pal system for selecting grand juries and adjusted property theft thresholds for inflation for the first time in more than two decades — a change that is likely to push incarceration rates down significantly within five years.

To be sure, Texas has a long way to go. Indeed, to some extent the state was able to enact big reforms because we began with a system so deeply slanted in the other direction. The United States famously has 5 percent of the world’s population and 25 percent of its prisoners, with Texas incarcerating more people than any other state, by far. With Louisiana, we are the global epicenter of mass incarceration.

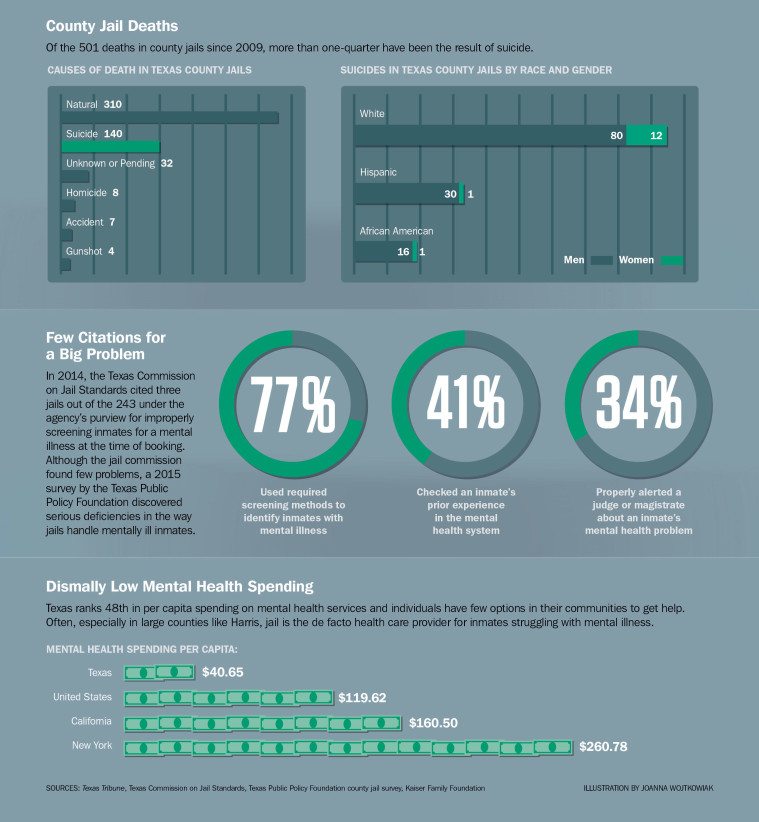

As long as prisons were viewed as mainly a jobs program, it didn’t seem to matter whether filling them up improved public safety. Instead, criminal justice fulfilled more practical, if less high-minded, goals. As the Legislature defunded mental health programs, prisons and jails provided a safety valve for warehousing the mentally ill whom state leaders wouldn’t pay to treat. (The Harris County Jail is the largest mental health institution in the state.) If poor, inner-city schools weren’t preparing minority youth to participate in the workforce, prisons would keep them out of sight, out of mind.

Municipalities loath to raise taxes showed no compunction about mulcting poor people for fines and fees, jailing them if they couldn’t pay. Underfunded hospitals even got in on the act, relying on traffic enforcement to pay for trauma care for the uninsured. In essence, criminal justice came to be viewed as a cash cow that at times seemed to serve every purpose under the sun except securing justice. And the public accepted all this because the only people who suffered were, after all, “criminals.”

Today, the system still plays those roles, which means reform is not inevitable. But increasingly, a chorus of voices from both the left and the right are calling for change. Tea party Republicans have recognized prisons and jails as Big Government’s epitome and police as its liberty-violating agents. At the same time, the Black Lives Matter movement’s national arrival has energized Democratic constituencies opposed to mass incarceration.

Today’s criminal justice politics pits those left-right factions against the shrinking moderate Republican middle.

We stand in a unique moment in history where the opportunities for reform in Texas appear greater than any time since the progressive movement of the 1920s and ’30s. So where is all this headed? Or, as Observer Editor Forrest Wilder asked when soliciting this piece, “What’s next for criminal justice reform?” Let’s highlight the topics most likely to rise to the fore in the 85th Texas Legislature in 2017, and beyond.

Sandra Bland Aftermath

Gil Scott-Heron declared that “the revolution will not be televised,” but he didn’t have a cellphone then, and in the 1970s, police cars weren’t equipped with cameras. The wrongful arrest of Prairie View A&M alum Sandra Bland and her untimely death last summer in a Waller County jail detonated across Texas like a bomb, and all of it was televised. The infamous video of Bland’s arrest — in which a since-fired state trooper bullied her, attempted to drag her out of her car, then threatened to “light [her] up” with a Taser for not putting out her cigarette — sparked national outrage.

Texas will almost certainly see tea party legislators pushing in 2017 to ban most arrests for non-jailable Class C misdemeanors (Bland was arrested for failure to signal a lane change). The Legislature passed a similar bill in 2001, only to see it vetoed by then-Governor Rick Perry. But with backing from grassroots conservatives such as state Senator Konni Burton, the idea has taken on new life.

Famously, Bland died in jail. She didn’t have $500 to post bond, and so she remained incarcerated even though she had local ties, a new job at Prairie View A&M, and wasn’t a flight risk. Nearly all Western nations and four American states have abolished money bail and instead switched to a risk assessment system to decide whether defendants must remain locked up while awaiting trial. State Senator John Whitmire, a Houston Democrat and chairman of the Criminal Justice Committee, has announced that bail reform will be his highest priority next session.

And finally, the public was transfixed by the televised battle between Bland’s family and Waller County after jailers released footage of her booking to prove she wasn’t murdered. What people saw was a woman who died needlessly in a system without mercy over a pointless traffic stop. That was the first aspect of the story to garner a policy response. House County Affairs Chairman Garnet Coleman held a hearing and interrogated state regulators on suicide prevention. Then, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick issued an interim charge to Whitmire’s committee directing it to find ways to reduce the number of jail suicides. Whitmire responded by announcing the state would adopt a “zero tolerance” approach to suicides in jail, but the most significant preventive changes cannot happen until the Legislature meets next year.

Reducing Mass Incarceration

In 2007, the Legislature passed nationally renowned reforms diverting thousands of low-level offenders from prison to the probation rolls and creating short-term punishments for parole violators instead of revoking them all back to prison.

These changes capped the steep upward growth of Texas’ incarcerated population, reducing probation and parole revocations and ultimately allowing the state to close three prisons. Last session’s changes to property theft thresholds should further reduce incarceration rates in the coming years. But there are still 109 facilities scattered around Texas housing more people than any other state, and three-quarters of the total held by the federal government. About half are locked up for nonviolent offenses.

Nationally, a bipartisan #Cut50 campaign has arisen with a call to reduce incarceration levels by 50 percent. Texas won’t reach that goal any time soon, but legislators for the first time in two decades appear ready to consider sentencing reform. The next big category of nonviolent offenses targeted by reformers will be low-level drug crimes, particularly possession offenses involving fewer than 4 grams of a controlled substance. Reducing those penalties to a Class A misdemeanor would save the state hundreds of millions of dollars, freeing up funds to supervise offenders on probation and provide treatment services they don’t receive in prison.

In addition, the push to reduce penalties for possessing small amounts of marijuana is fast becoming a common-sense touchstone of bipartisan reform. The national Marijuana Policy Project has launched a multiyear legislative campaign in Texas to promote the issue.

Tea party state Representative David Simpson pushed the envelope further last session than his colleagues were willing to go, calling for complete legalization of marijuana because “all that God created is good.” But his suggestion altered the terms of debate on the issue at the Texas Capitol, making suggestions to reduce penalties for small-time possession seem downright moderate.

Simpson’s legalization bill and another bill decriminalizing low-level pot possession passed out of committee in the House last year, and the latter appeared to have sufficient floor votes to pass.

With oil revenues plummeting, these sorts of cost-saving reforms will arrive at the Capitol in 2017 with significant momentum.

Juvenile Reform

When child sexual abuse scandals rocked the Texas Youth Commission in 2007, Texas youth prisons housed around 4,200 youthful offenders in facilities around the state. Today, most of those units have been closed and state youth prisons in the renamed Texas Juvenile Justice Department hold only around 1,000 inmates — an astonishing 76 percent reduction.

Even more remarkably, juvenile crime declined in the intervening period. There wasn’t a public safety justification for locking up so many youth, and the Legislature last session moved to divert even more youthful offenders from state lockups to community-based corrections.

Even so, Texas remains a regressive outlier in one key respect: Teenagers are viewed as adults by the criminal justice system once they turn 17, even though federal law and a general national consensus don’t consider them adults until they turn 18. This creates a serious risk of abuse of young inmates by older ones and puts most county jails out of compliance with the federal Prison Rape Elimination Act, which treats 17-year-olds as juveniles. Adult jails haven’t been modified to meet minimum juvenile standards, and retrofitting them would cost a fortune. For those reasons, in 2015, the Texas Sheriffs’ Association emerged as one of the strongest backers of “Raise the Age” legislation. Lawmakers have already said they’re coming back for another try next year.

Asset Forfeiture

Conservative activists with the Texas Public Policy Foundation and the Institute for Justice are making an aggressive push to scale back asset forfeiture in Texas, hoping to replicate New Mexico’s newly enacted policy of requiring a criminal conviction before assets can be seized. Right now, no conviction is required for the state to seize assets, and the standard under which it does so — “preponderance of the evidence” — is a far cry from “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

After asset forfeiture practices were linked to racial profiling at traffic stops in Tenaha near the Texas-Louisiana border, liberals began to see the wisdom of this conservative bailiwick and increasingly have come to support most of the reforms being promoted by the property-rights crowd. As it turns out, people of color don’t like their property being unjustly seized any more than white people do.

Local prosecutors and law enforcement agencies get to keep most of the assets they seize, creating unfortunate incentives for them to maximize forfeitures.

Eliminating asset forfeiture where the state cannot secure a criminal conviction would deal a mighty blow to the War on Drugs, removing perhaps the greatest incentive for police and prosecutors to prioritize drug enforcement over crimes with victims. Conservatives may be leading the charge here, but there are many reasons for liberals to back their play.

Transparency

Several proposals likely to make their way into legislation in 2017 deal with lingering transparency issues that prevent the justice system from functioning properly, concealing conduct in which the public has a significant interest.

For starters, in 2015 Texas became one of the first states to require law enforcement agencies to report to the attorney general whenever they shoot someone. As it turned out, many such shootings, fatal and nonfatal, were never reported publicly. Now, it’s become clear that gaps in reporting remain, starting with victims’ names. Look for legislation next year bolstering information in these new police shooting reports to make them more useful for the press and advocates.

Similarly, a 2015 bill related to police body cams — considered an important tool to curb police misconduct — also unfortunately made video from most encounters with the public secret. Dashcam video from police cars has never been secret. Releasing it has created no discernible problems, and there’s no good reason for body cam footage to be any different. Legislation will likely be filed in 2017 to make those policies consistent.

Finally, although the Legislature passed the Michael Morton Act in 2013, requiring Texas prosecutors to operate under “open file” policies, a major gap has been identified: Departments in dozens of cities keep most police misconduct secret, even if prosecutors are legally required to hand over the information as “mitigation” evidence. If prosecutors don’t know about misconduct, they can’t reveal it. The issue came to the fore last fall when a false conviction out of San Antonio was overturned. A police officer beat a handcuffed suspect, then accused him of assaulting an officer, for which the man pleaded no contest. SAPD didn’t reveal that the officer had been disciplined for lying about the incident and, when it later came out, the conviction was overturned. Even (perhaps especially) prosecutors want this problem resolved.

This list is by no means exhaustive, nor will all these bills come to fruition during the 85th Texas Legislature. But these reforms provide a sense of which issues the Lege could prioritize that have bipartisan support and a decent chance of passage. And the fact that legislation like this is even possible speaks to how far the state’s political class has moved since the bad old days.

Debates over criminal justice policy generally do not center around partisan divisions in Texas. When Ann Richards and the Democrat-controlled Legislature pushed to triple the size of the prison system in the 1990s and quicken use of the death penalty, they found bipartisan support. Now that Republicans control the Legislature by a 2-to-1 margin, more small-government-oriented and libertarian members are joining with Democrats to forge a new, if sometimes tenuous, bipartisan consensus for shifting policies in the other direction. These dynamics present opportunities over the next two to three legislative cycles that were unthinkable 20 years ago. But it’s not happening just because Republicans had a change of heart, which is a common assertion in the press. It’s because everybody did.