A Sweltering Summer in Texas, Courtesy of Climate Change

A weakening El Niño, assisted by climate change, is driving scorching temperatures in Texas.

Like the 14 months preceding it, July is likely to break global heat records. Month after month, average temperatures have exceeded those of the last 136 years, since record-keeping began.

So far this year, a brutal heat wave has killed more than 300 people in India. California’s Death Valley set a new record for hottest June, where the average temperature rose to 101.9 degrees Fahrenheit, 6 degrees higher than its 105-year average. And last week in Kuwait, temperatures rose to 129.3 degrees, the highest temperature recorded outside of Death Valley and the highest in the Eastern hemisphere.

Though this summer isn’t as brutal as the scorcher of 2011, Texas hasn’t been spared, either. Parts of West Texas, including Lubbock, Midland and El Paso, are close to breaking temperature records for July. And along the Gulf Coast, night time temperatures have consistently remained above 80 degrees, providing little reprieve to night owls in Houston and elsewhere.

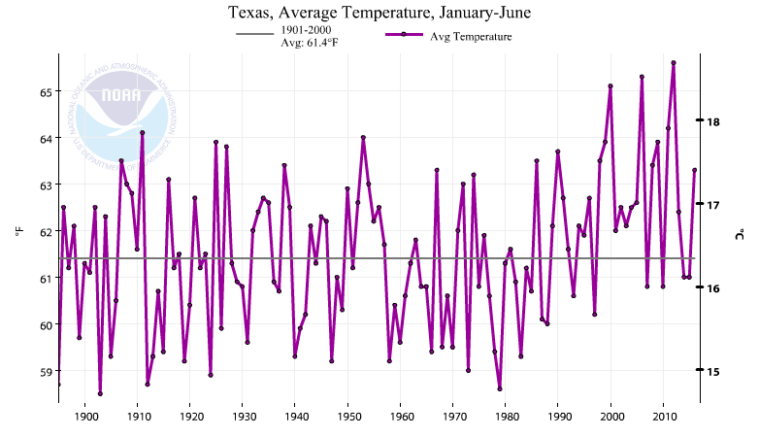

The temperatures in the last month are evidence of a new normal in Texas, a state typically protected from long periods of extreme heat during years when the El Niño weather pattern takes hold. That paradigm is slowly shifting as climate change overrides El Niño and takes on a larger role in influencing the state’s weather patterns.

“The impact of climate change was higher than the impact of El Niño,” said state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon. “El Niño, rather than making us cooler than normal, made us not as abnormally warm.”

Typically, El Niño brings wetter and cooler weather to Texas. Without the effect of climate change, the state would have likely seen lower than average temperatures this year, Nielsen-Gammon said. But the overall warming trend superimposed on El Niño has resulted in temperatures closer to, or warmer than, the average, he said. The first half of this year has been the third warmest on record in the United States.

That climate pattern contributed to temperatures in Lubbock soaring to 108 degrees on July 13, beating a previous record of 107 degrees for that day from 1933. The temperatures are a cause for concern among cotton farmers who worry the excessive heat will damage their crops, and the city’s utility company which has already come within 10 megawatts of its peak power consumption record set in 2011. And there’s no relief in sight: Lubbock is poised to break the record for hottest July. As of July 24th, its average temperature was 86.2 degrees, higher than the monthly average record set in 2011.

El Paso and Midland have also similarly surpassed monthly average temperatures records for July. El Paso’s average temperature as of July 24th was 89.3 degrees, higher than the city’s 1994 record for the month at 88 degrees, and Midland’s 24-day average was 88.9 degrees, exceeding its 2011 record of 88 degrees.

Those temperatures have been particularly hard on the homeless. At least one homeless person’s death has been linked to the heat in Midland. At one Lubbock transitional housing facility, the triple-digit temperatures have pushed the homeless out of their tents during the day when the heat gets unbearable. Those residents are depending on donations of ice cream, popsicles and water to stay cool.

While West Texas has been seeing sweltering day time temperatures, Texans in Houston have been feeling the heat with high night time temperatures. Minimum temperatures in the city have stayed above 80 degrees nine days this month, the third-highest record for a July in Houston.

When the sun goes down, the heat absorbed by the earth during the day is radiated back into the atmosphere. As a result, the ground cools down and temperature drops at night. But if the there is more water vapor in the atmosphere, the heat trying to radiate away ricochetes back to the ground and gets trapped.

“There’s been a lot of clouds in Houston and the nights have been completely clouded over,” said Ron Sass, a professor emeritus of natural sciences from Rice University. Those clouds act like an insulating blanket at night, Sass said.

The warmer night times are part of a larger trend that climate scientists have been noticing globally. As the planet warms up, researchers have found that nights have been warming more rapidly than days. Part of the reason is that during the day the layer of air closest to the ground — called the boundary layer — heats up, expands and is thicker than at night. A thicker boundary layer is less susceptible to changes in temperature. But at night, as temperatures drop, the boundary layer contracts, making it more likely to warm up.

Coastal areas in general tend to have higher nighttime temperatures because moisture from the sea is carried ashore. Galveston, for instance, typically has higher nighttime temperatures compared to Houston, since it’s closer to the coast. It had 20 days with temperatures above 80 degrees, compared to Houston’s nine.

Nielsen-Gammon hypothesized that extreme rainfall during the spring, which added to the moisture in the soil and increased water levels in rivers and lakes, is likely also contributing to an increase in the minimum temperatures in Houston. As the moisture from the ground evaporates during the hotter months, it’s helping trap heat, he said.

The severe rainfall in the first half of this year was a result of a strong El Niño. That pattern is unlikely to be repeated next year as La Niña, which tends to create drier and warmer conditions in Texas, takes hold.

The National Weather Service has predicted that there is about a two-thirds chance of La Niña developing between August and October. El Niño and La Niña, which are two opposite phases of a natural weather cycle across the Pacific Ocean, typically last nine to 12 months on average.

The last La Niña cycle in 2011, with an assist from climate change, led to one of the worst droughts the state has seen.

If climate change continues to raise global temperatures, as scientists predict it will, extreme weather events like the 2011 drought will become routine — And Texans will have to get used to more sweltering weather.

Correction: An earlier version of the story reported that Houston had 19 days of nighttime temperatures above 80 degrees based on erroneous data.