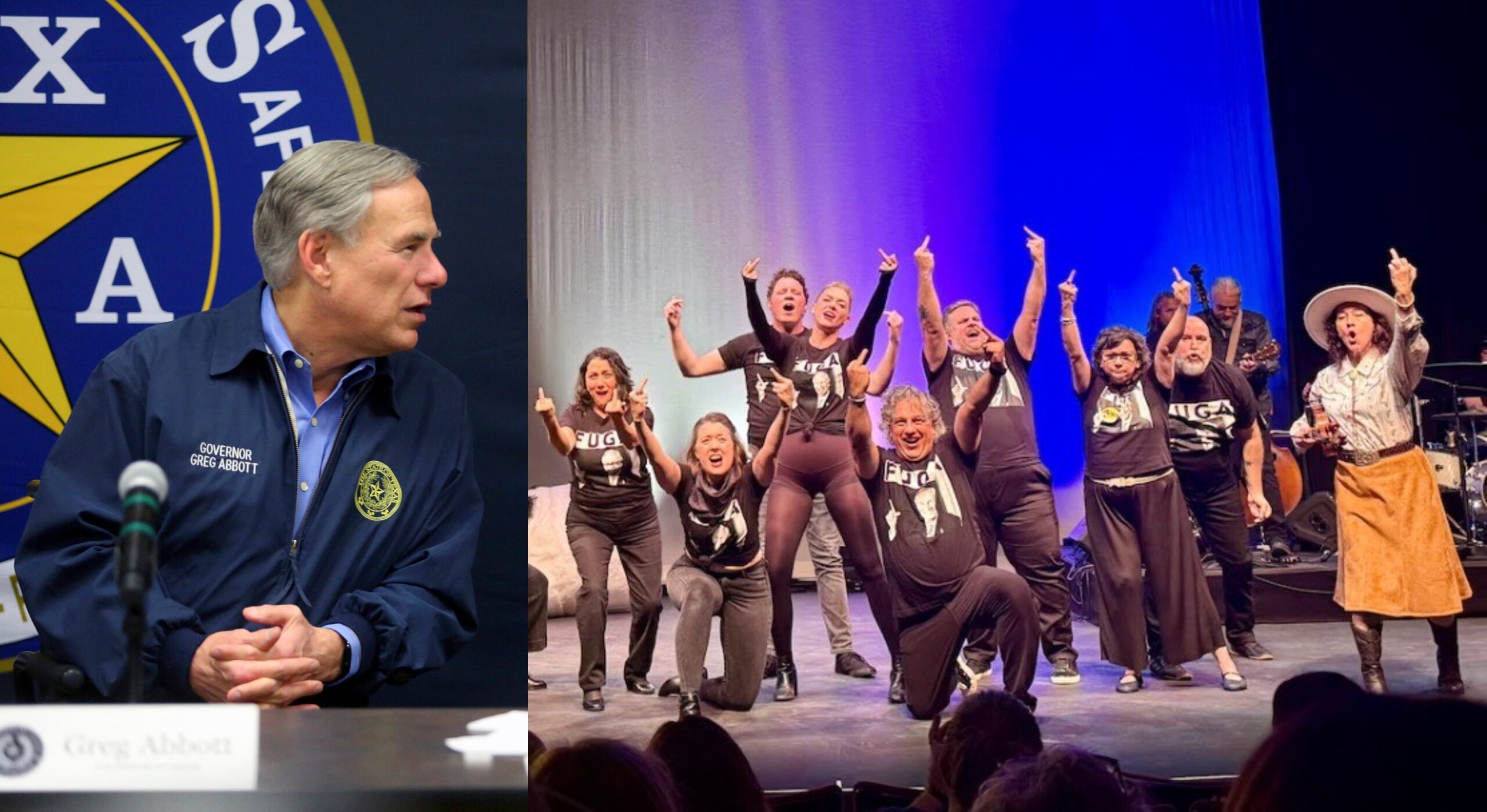

The Gospel According to Texas Democrats

Governor Greg Abbott said we wouldn't hear the 'word of God' at the Texas Democratic Convention. He was wrong.

Governor Abbott likes to tout his defense of the Ten Commandments display at the Texas Capitol. But he might want to take another look at them, specifically the one about not bearing false witness.

In his keynote address at last month’s Texas GOP convention in Dallas, he claimed — to enthusiastic applause — that you’ll never hear the word of God at a Democratic convention.

Sorry, governor, but that’s just not true. Here at the 2016 Texas Democratic Convention in San Antonio, it’s fairly easy to run into expressions of religious faith — and yes, even the word of God, although maybe not always the one the governor has in mind. What you won’t find here is the God-Blessed-Texas, America-Is-a-Christian-Nation, Holier-than-Thou brand of religion that was on offer in Dallas at the Texas GOP convention in May.

The GOP convention approach to religion — well, Christianity — had all the subtlety of a street-corner evangelist waving a copy of the Bible in the air and hollering. By contrast, the delegates and elected officials at the Texas Democratic Convention make the place feel more like an Episcopal parish or a Reform Jewish synagogue — it’s a faith that is quiet, congenial, neighborly and tolerant.

Thursday evening before the official kick-off of the TDP Convention, a large and diverse crowd of Democrats gathered in Maury Maverick Plaza in downtown San Antonio to help the Muslim Democratic Caucus celebrate iftar, the end of the day’s Ramadan fast. Before the food was distributed, a young Muslim man chanted the adhan, or call to prayer, parts of which are traceable to the Qur’an. If that doesn’t qualify as the “word of God” for the governor, it certainly does for Muslim Texans.

The Friday convention schedule also featured meetings of the Jewish Caucus and the Muslim Caucus — but also a standing-room-only Secular Caucus meeting. The fact that secular Democrats felt the need to carve out their own non-religious space testifies to just how pervasive religious beliefs and assumptions (and predominantly Christian ones) continue to be in American politics, even among Democrats.

For instance, Friday’s opening general session featured an invocation by U.S. Congressman Al Green. But even Green’s was a resolutely multi-faith prayer, addressed to the “most gracious Creator,” whom we know “by many names.” Green spoke of this Creator as the one who inspired Milton to write Paradise Lost when he was blind, Beethoven to compose the Ninth Symphony when could not hear, and a daughter to forgive her mother’s murderer; he asked that Creator of many names to similarly inspire Texas Democrats to unite and work to defeat the forces of hate and division. While the invocation avoided referring to any specific religions (for example, Green didn’t invoke the name of Jesus at the end), it might have been a bit too religious for members of the Secular Caucus.

Unlike their GOP opponents, who increasingly espouse a kind of Christian dominionism (an ideology that calls for Christians to take dominion over government and other parts of life), Texas Democrats call for preserving America’s tradition of church-state separation. The 2014 Texas Democratic Party platform insists that public resources not be used to support purely religious positions or activities, and that “entangling government with religion is dangerous to both government and religion.” It also declares that “we must never use the power of government at any level to impose our personal religious observances on others.”

That’s in the abstract. How do real, live, flesh-and-blood public officials manage to be guided by their personal religious beliefs (or lack thereof) without making policy that infringes on the religious liberty of others?

I put this question to two Democratic lawmakers who make no secret of their own religious identities: U.S. Congresswoman Eddie Bernice Johnson, a Baptist; and Texas state Senator Sylvia Garcia, a Roman Catholic.

“I take my religion and my religious beliefs very seriously,” Johnson told me by email. “I am a devout Christian.” And her religious faith motivates her politics: “My religion teaches me to be my brother’s keeper. Christianity teaches us to care for the least of these, to look out for the poor, and imprisoned, and elderly. That is why I have focused my entire career on helping the poor, trying to end hunger and homelessness.”

Garcia gave me a similar account of her own spirituality: “My faith shapes much of my life, not just my approach to politics,” she told me. “Jesus always sought to help the poor and oppressed, and my political life has been spent making sure that everyone, including people on the margins of society, are included in the process.”

However, both lawmakers also are strong believers in separation of church and state. “The role of religion in politics,” Johnson said, “is to inform individual politicians on their own beliefs and morals and world views. Religion is embodied in an elected official’s basic beliefs, but it should not be imposed on others. One of the beauties of America is the ability to practice your religion free from any form of persecution.”

Garcia echoed this sentiment: “Our faith can shape us and focus us, but it can’t be something we impose on others.” This stance allows Garcia to take a firmly pro-choice stance, she said, despite the fact that her own Roman Catholic Church considers abortion a sin. “While not everyone agrees when a fetus becomes a person,” she explained, “we can all agree that a woman who is pregnant is a person. I believe that each woman is capable of making her own decision with her doctor’s advice, her family’s support, and the faith in her heart.”

I also asked Garcia about the belief, common in GOP circles these days, that America is a “Christian nation.” She doesn’t buy it: “We should be a nation of the people, by the people and for the people. That means all people, not just ones who share our exact beliefs.”

That’s not far from the position expressed by members of the Secular Caucus here at the convention. As I reported earlier, Secular Caucus member David Smalley of Garland put it this way: “Public policy is just that: It’s for the public, and you cannot dictate religious beliefs or legislate religious behavior based on your interpretation of ancient doctrine.” And to people of faith, Smalley had this to say: “We’re not here to take anything away from you. … We just want to hold on to our rights to live without your religion if we so choose.”

“At the end of the day,” he added, “what we’re fighting for protects you, too.”

So, are Democrats the capital-G-Godless secularists their GOP opponents paint them out to be? Some are, but many are deeply religious, and their faith motivates their lives and their politics.

Can you hear the “word of God” at a Democratic convention? Certainly you can — though not, perhaps, in a form that über-evangelical Republicans might recognize.

And while Democrats’ approach to religion may lack the Bible-thumping zeal of some Texas Republican gatherings, who knows? That approach might just show more respect for religion and for individual religious freedom than the alternative.