Report: Oil and Gas Production Is Making People Sick in Rural Texas

“The price of living near oil and gas shouldn't be giving up your health.”

Sue and Jim Franklin’s double-wide mobile home at the foot of the Davis Mountains in far West Texas is usually sealed up tight with the air conditioner blasting. One reason is because they live in Reeves County, a crown-shaped section of the scorching Chihuahuan Desert at the Texas-New Mexico line. But another reason, the Franklins say, is to defend against fracking wells that spew dangerous gases into the air, a pernicious and ever-present threat to their health.

Reeves County, population 14,732, sits atop the Permian Basin and has been the site of some of the most frenzied hydraulic fracturing in the state. Though the fracking boom started in 2011, it didn’t reach the Franklins’ 10-acre plot of land until early 2017. That year, four wells were drilled nearby, some within a half-mile of their home. In the spring, Sue’s nose started bleeding and she began having breathing problems.

top of the rightmost tank vents methane and toxic volatile organic compounds. Earthworks, Clean Air Task Force

“Some days it’s not that bad. But some days it’s really bad,” she told the Observer. Sue takes allergy medicine and uses nasal spray to help her breathe, as recommended by her doctor. Jim said he started experiencing “debilitating” headaches and respiratory problems around the same time from exposure to the emissions, which can include volatile chemicals like methane. “Now every morning we get up coughing and hacking… It makes us sick. We’ve both missed days of work because of being sick,” Jim said.

The Franklins are one of five case studies included in a new report by two environmental advocacy groups on the health dangers faced by people who live near active oil and gas operations. Earthworks and Clean Air Task Force conclude that concentrated energy development activity in rural America is inundating nearby communities with greenhouse gases and volatile chemicals, making people sick and spurring climate change. One other Texan (a military veteran in frack-happy Karnes County) is featured in the report, along with people in rural areas of Utah, Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Air pollution in Texas’ population centers is well-documented. But thanks to oil and gas development in broad swaths of sparsely populated areas across the state, the people who live in some small communities are also gasping for breath, said Alan Septoff, an Earthworks spokesperson. “There’s a general impression that air pollution is a problem in urban areas, that there’s dirty air in urban areas and clean air in rural areas,” he said. “But the oil and gas industry turns rural areas into urban areas in terms of air pollution.”

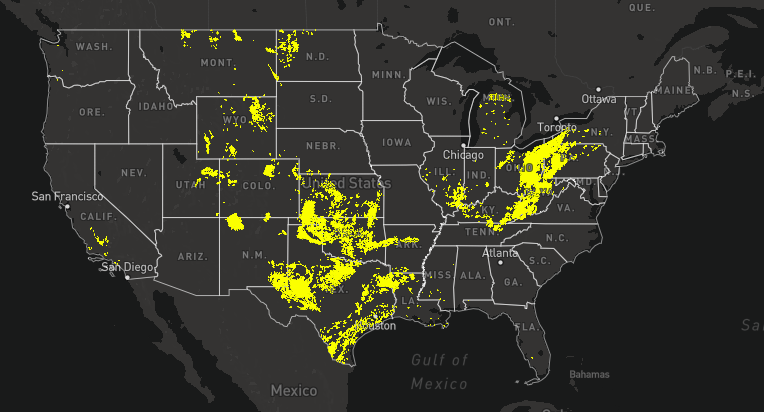

In virtually every corner of the state, 116 Texas counties are at elevated cancer risk due to oil and gas emissions, a “threat map” previously released by the environmental groups shows.

Two byproducts of oil and gas production that are of significant concern are methane, a potent greenhouse gas that leaks from oilfield equipment, and benzene, which has carcinogenic properties, the report notes. In the United States, more than 9 million tons of methane and other dangerous chemicals are spewed into the air each year. The report’s authors say that nationally the air pollutants are associated with 750,000 asthma attacks in children during the summer and 500,000 days of missed school. The pollutants are also linked to “increased risk of cancer and respiratory disorders” and the formation of ozone smog, which can result in a bevy of respiratory issues.

“Some days it’s not that bad. But some days it’s really bad.”

For the most part, Texas environmental regulators don’t monitor methane emissions from the oil and gas industry. Over a 20-year period, methane is 84 to 87 times more powerful than carbon dioxide at driving global warming, according to NASA. The Environmental Protection Agency under the Obama administration enacted rules requiring oil and gas companies to check pipelines, oil wells and other equipment for methane leaks and to make repairs to prevent future leaks. But the Trump administration, under the guidance of now-resigned EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, rolled back those rules, which now are not enforced.

“Texas regulators service the oil and gas industry first and the public second. Their approach to regulation reflects that,” said Septoff, the Earthworks spokesperson. “Rural Texans should read this report because it could be them. The price of living near oil and gas shouldn’t be giving up your health.”

The other Texan featured in the report is a Karnes County resident identified only as George, who said that emissions from oil and gas facilities near his home gave him headaches and fatigue, problems he says only cropped up after the fracking boom came to Karnes County in 2011. “We just don’t know what we’re breathing, what it can cause, and how much of it is in the air we breathe,” George said.