Report: Texas Prosecutes More Truancy Cases Than All Other States Combined

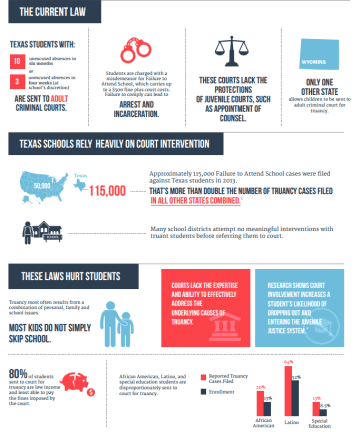

Texas prosecutes kids for missing school more zealously than any other state, according to a new report released this morning, and poor, minority and special education students are disproportionately targeted.

Texas Appleseed, a social justice advocacy group, authored the report on truancy prosecution, finding it a punitive and ineffective practice that has done little to increase attendance and graduation rates while dragging juveniles into the adult criminal system.

Just one of the astounding facts revealed in “Class, Not Court: Reconsidering Texas’ Criminalization of Truancy,” is that in 2013 Texas prosecuted approximately 115,000 truancy cases–more than twice the number of all other states combined.

These prosecutions fall heavily on minority students. In the 2013-14 school year, almost 20 percent of reported Failure to Attend School court referrals statewide involved African-American students, despite the fact that African-American students represent less than 13 percent of the student body statewide. Likewise, 64 percent of reported cases involving Hispanic students, though they represent only 52 percent of the student body.

The report suggest that a better, more effective solution for handling truancy cases may be for schools and courts to provide prevention and intervention services for at-risk children to get them back into school.

“We know the most effective programs to address truancy really hone in on the underlying reasons that a student is not attending school and addressing those underlying causes of chronic absenteeism,” said Deborah Fowler, the executive director of Texas Appleseed. “Those are the things that are missing in the Texas system. In Texas, we have a very court-centric approach that is very one-size-fits-all.”

The court approach, which involves fines students can’t pay and criminal records that can follow youth into adulthood, often fails to grapple with the realities kids are facing: chronic health problems, homelessness, family violence and the need to work for survival.

“We see when we talk to families that there are complex and varied reasons that kids miss school, and it often doesn’t really resemble what I think most people commonly think of when they think of truancy,” Fowler said.

Students with disabilities also make up a significant percentage of students charged with truancy. While special education students represented only 9 percent of students statewide in the 2013-14 school year, they represented 13 percent of court referrals for Failure to Attend School.

According to the report, many students with disabilities miss school to receive essential disability-related treatment from doctors and speech, occupational and physical therapists. Sometimes schools, under pressure from the state to meet attendance goals, refuse to excuse absences for therapies that parents and outside providers believe are essential, but schools do not prioritize.

“Every time a student misses school, even for something that should be excused, you run the risk of sloppy record-keeping in the attendance office. You also run the risk of a parent or a student forgetting to turn in their excuse and a higher chance of being referred for those absences,” said Dustin Rynders, an attorney for Disability Rights Texas.

Each truancy fine can run up to $500. Because 79 percent of those charged are economically disadvantaged, many of the tickets go unpaid. If the student’s family can’t pay the fines and court costs, that student could face arrest and incarceration when she turns 17.

“The students who are most likely to be sent to court and fined are the students who can least afford it. We have an overrepresentation of students who are classified as economically disadvantaged going to court for truancy cases. So it’s families that are least able to pay fines that are getting saddled with these fines,” said Fowler.

The report also describes another troubling sanction: Some judges are ordering students to “unenroll” from school and take the GED. In other words, courts in Texas are ordering children to drop out of school as a punishment for not going to school. Over a three-year period, 6,423 students who were ordered to drop out and take the GED then failed the test.

The report also provides suggestions for better ways to handle truancy cases. Texas Appleseed encouraged legislators, school districts and Texas Education Agency to decriminalize truancy so that it is no longer treated as a crime in adult criminal court, make all court referrals discretionary, and require effective school-based truancy prevention and intervention. The executive summary also emphasized the importance of requiring schools to produce complete data on truancy in a timely matter.

The report also provides suggestions for better ways to handle truancy cases. Texas Appleseed encouraged legislators, school districts and Texas Education Agency to decriminalize truancy so that it is no longer treated as a crime in adult criminal court, make all court referrals discretionary, and require effective school-based truancy prevention and intervention. The executive summary also emphasized the importance of requiring schools to produce complete data on truancy in a timely matter.

“What we have suggested is that the Legislature consider requiring schools to take a graduated approach before filing a case so they would have an initial intervention with the family that could simply consist of meeting with the family , talking to them and figuring out what’s going on and see what’s causing the chronic absences. If that didn’t work, then the next approach would be to refer them to a truancy prevention class or to a counselor or to a community based service that the family may need to really get at the underlying causes,” says Fowler.

Reporting data has become a problem. School districts are required to accurately report their truancy filings, but only half do, according to the report.

“We know that truancy reform is definitely on the radar for our legislature this session and we hope that ensuring that school districts report data accurately will be among the issues that the legislature addresses when it comes to the way truancy is handled in Texas”, says Fowler.

But Susan Steeg, a Travis County justice of the peace who handles truancy cases for three Austin-area school districts, defended the current approach toward truancy. She argues there’s no other proven way to get students back into school.

“What is on the table now is to repeal that law and there is nothing that is going to fill that void,” Steeg said. And what I’m afraid of is all the programs that we have in place with the courts that have juvenile court management won’t have a way to get those kids into court for the interventions that they sorely need.”

Steeg also defended the court-ordered GED tests.

“We see a lot of students where traditional classes are not in their best interest. We have several grade alternative choices here in Travis County. Besides GED courses, we have several diploma programs that are open to them, such as Austin Can Academy, American YouthWorks, and many of these programs are four-hour days, so the student can work part time also receive their high school diploma,” she said.

Fifteen bills filed related to truancy reform are in session now.

Fifteen bills filed related to truancy reform have been filed this legislative session. The House Juvenile Justice and Family Issues Committee will hear a host of truancy-related bills on March 11.