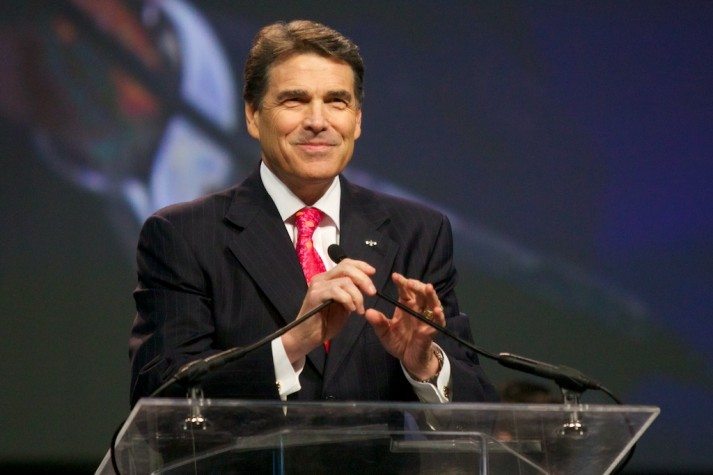

Rick Perry’s Post-Indictment Honeymoon Won’t Last

When most people get indicted on felony charges, it’s a bad time. Things start bad, and they stay bad. When Gov. Rick Perry got indicted on two felony counts, it kicked off a pretty great week for him. It started with a loud and premature verdict of innocence by the national media, continued through a trip to get ice cream, and ended in Washington, D.C. with a number of meetings with East Asian ambassadors. It was quite a show.

But unless Perry’s lawyers quickly quash the indictments, the rest of this process probably won’t go as smoothly. Perry needs to keep his core narrative about the indictments intact until the charges resolve themselves, and that’s going to be difficult to do as the case rumbles on. We’re likely to face a trickle—possibly a torrent—of new information, not only about Perry’s actions around the veto, but also his tenure as governor in general.

Separately, the story of the indictments is set to give new life to old stories about Perry’s improprieties, in much the same way Chris Christie’s bridge-related indiscretions gave rise to a narrative about his temper and vindictiveness toward political opponents. And Perry’s personality—best suited to offense—was well tailored to the first stage of this ordeal, but may trip him up going forward.

Here’s Perry’s story about the indictments, as outlined in a video released by his political action committee, PerryPAC: He saw a damaged public official, a woman who shouldn’t possibly hold office or any kind of responsibility, and took firm, narrowly targeted action to try to remove her. Now he’s facing political retribution from Democrats.

Parts of that narrative fall apart as soon as you look at them closely—particularly the notion that special prosecutor Michael McCrum, appointed to the case by a Republican judge in San Antonio, is an agent of Battleground Texas. But much of the rest of it could fall apart over the course of a trial, too.

Perry says his veto was about unseating Lehmberg, but it had significant consequences. As the Quorum Report’s Harvey Kronberg wrote on Thursday, Perry’s veto of the funding for the Public Integrity Unit “derailed more than 400 felony level tax and insurance fraud investigations allegedly committed against the State of Texas.”

In other words, Perry’s action didn’t just punish Lehmberg for her refusal to step down—it punished the state as a whole and Texas citizens generally. Think about that: Perry zeroed out the funding for more than 400 felony investigations because a local official wouldn’t step down when he wanted. Kronberg:

The Travis County Public Integrity Unit is the most under-appreciated law enforcement apparatus in the state. Fully 95% of what it does is pursue white collar crime in Texas and on behalf of the State of Texas – motor fuels tax fraud, insurance fraud and legal support for the smaller of Texas 254 counties that do not have the funding or expertise to pursue white collar crimes in their jurisdictions.

When Perry derailed the unit, the Travis County Commissioners Court stepped in and restored a portion of the funding—but the PIU had to slash staff and caseload. The state’s side in serious criminal cases that had nothing to do with Lehmberg’s troubles—or even, politics generally—suffered needlessly.

But the PIU investigates political corruption too. Kronberg dismisses the relevance of the investigation into the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas as a factor in Perry’s motivation for wanting a friend in control of the DA’s office, but points to other possibilities.

This trial might be the most penetrating look at Perry’s workshop in the 14 years since he took office.

“It is far more interesting to look at the Public Integrity Unit investigation of Republican AG candidate Ken Paxton and Perry Regent appointment Wallace Hall,” Kronberg writes. “Had Lehmberg resigned, it is doubtful Perry’s appointed replacement would be very interested in either criminal referral.” There’s no shortage of possible motives for Perry’s intervention in the PIU, even if those motives don’t necessarily matter to the legal case against him.

If the trial gets going, there’s really no telling what’s going to get dredged up in the discovery process. What internal communications, what private conversations will we become privy to? This trial might be the most penetrating look at Perry’s workshop in the 14 years since he took office. There’s no politician that comes away from that level of scrutiny looking good.

If Perry still intends to run for president—it will be significantly more difficult to do while facing a marathon legal battle, since he needs to be up and running at full strength in just a couple of months—here’s another consideration. The question of ethics, which now dangles from his candidacy, invites follow-up questions about Perry’s past scruples.

There are the top-level ones—like the use of the Texas Enterprise Fund and CPRIT—and potential improprieties which have faded a bit in most people’s memories, like Perry’s history of inordinately profitable real estate deals conducted with dubious figures like Austin developer Gary Bradley. The criminal case, combined with a presidential campaign, gives national media—the only media Perry cares about—a reason to start looking into these stories again. They never got far last time he ran, but the framing will be different now.

Here’s another question: Does Perry have the right temperament to ride this out? His blustering offense works great in certain cases. But there will be other situations that call for subtlety and tact. Take his statement last Saturday, just after the indictments came down, when Perry predicted “that this farce of a prosecution will be revealed for what it is, and that those responsible will be held to account.” A Travis County judge subsequently warned that it could constitute a second-degree felony. What you’re seeing is a man who hasn’t been accountable to nearly anybody in a long, long time.

Temperament is one thing, ability is another. Before the indictments, the question about Perry was: Is he more prepared this time to face primary voters? In New Hampshire last Friday, we got some more data points on this question. In a room full of Granite State businessmen, Perry seemed oddly unfamiliar with the felonies he had just been charged with, telling the crowd he had been charged with bribery (he hadn’t.) “I’m not a lawyer, so I don’t really understand the details here,” he told the crowd, who were doubtless reassured.

That night, according to the Texas Tribune’s Jim Malewitz, he told a house party that the states were “lavatories of democracy.” Somewhere out there, Rand Paul and Ted Cruz are dreaming of the Ames Straw Poll and smiling.