Cash-Strapped Rural Texas Schools Look to Universities for Help

From East Texas to the Rio Grande Valley, universities are helping struggling schools train staff, start enrichment programs and expand space for district activities.

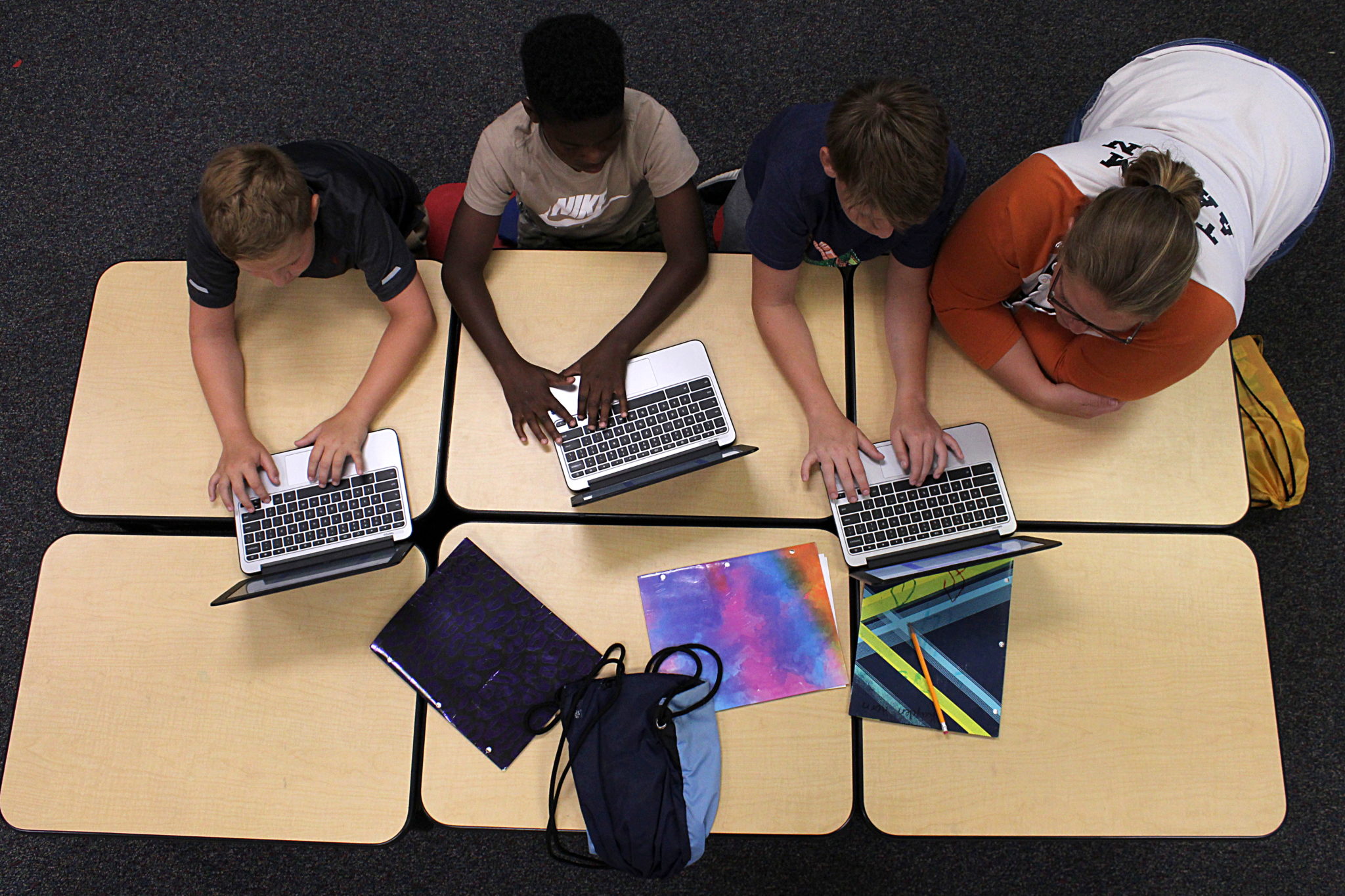

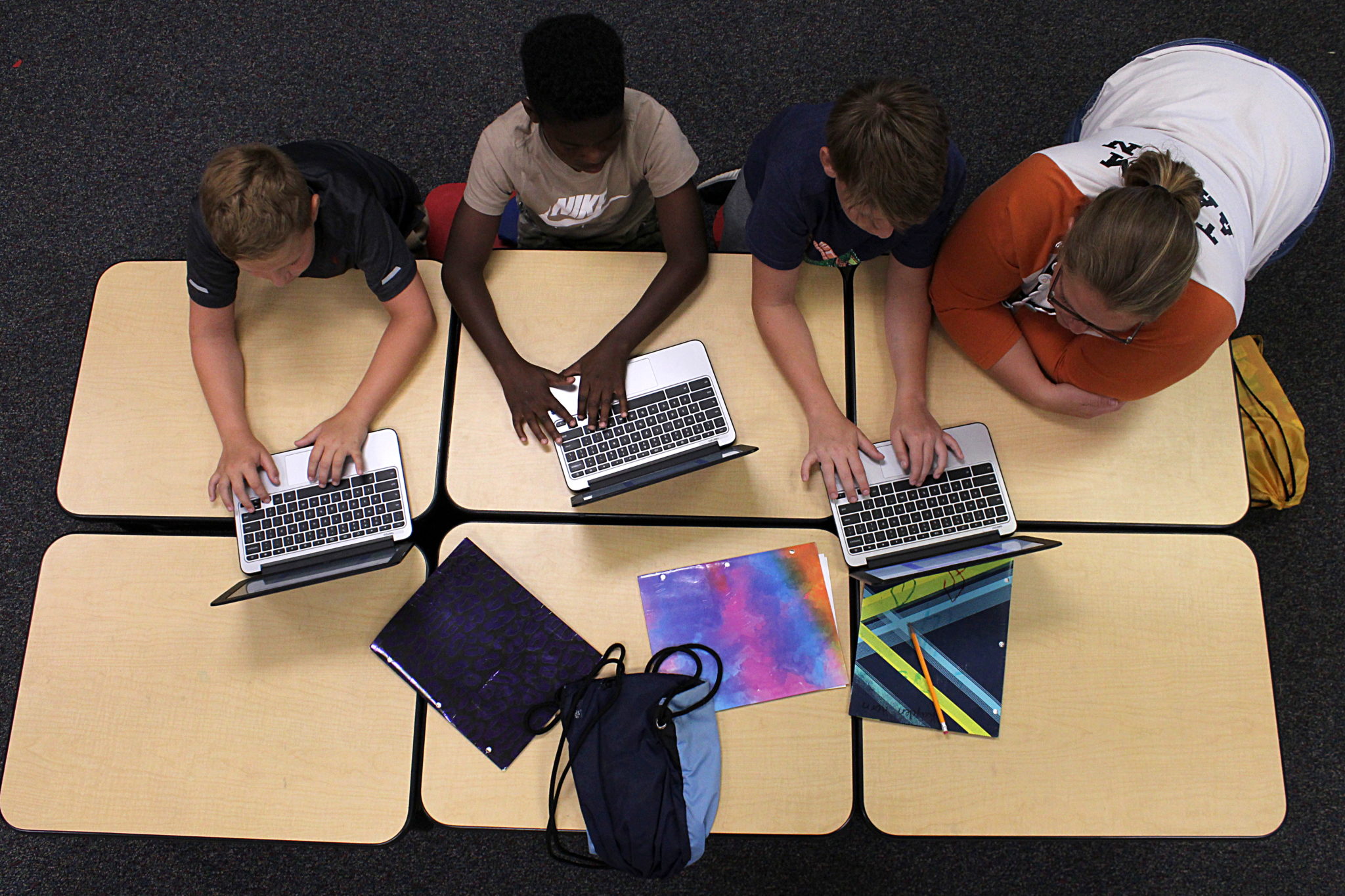

On June 20, a few weeks after Commerce ISD released students for the summer, about 10 fifth-grade students gather in teacher Cari Aaron’s classroom, playing math games on computers. Sitting cross-legged at a low table in the middle of the room, 11-year-old Adrian Hawkins hollers, “Get it! Get it!”, jabbing his index finger at 10-year-old Kyle Foster’s laptop screen. Kyle is frantically trying to drive his virtual car to extinguish ticking time bombs before they explode. To succeed, he has to enter the correct x and y coordinates.

He doesn’t get there in time. “I got blown up,” Kyle says.

At the other end of the table, Jackson Taylor, 11, says he doesn’t exactly get the point of the game, but he’s probably just being humble. He did, after all, set the classroom’s record score just earlier that day. “I’m gonna beat Jackson!” says Adrian, turning to his own laptop and starting the car. “Hey, I’m doing donuts. Look!”

Aaron, the teacher, directs them to the door. It’s time for lunch, where Adrian, Kyle, Jackson and their classmates are served trays of pizza, peas, sliced carrots and milk. Later about 60 students, from kindergarten through fifth grade, will be bussed across town to Texas A&M University-Commerce, the district’s partner in the summer program, to spend the afternoon swimming, rock climbing and hiking. This afternoon’s activity is archery.

The joint program, called ASPIRE, is now in its second year. It’s designed to remedy “summer learning loss” — that is, the stuff kids forget between semesters. The problem tends to disproportionately affect poor and minority students, and can eventually put them grade levels behind their better-off peers.

It’s a bit surprising that Commerce ISD, a 1,600-student district an hour northeast of Dallas just off Interstate 30, is in a position to add new services. Sixty-two percent of its students are classified as “economically disadvantaged.” The city of roughly 9,000 people has a median household income of $19,000, and 47 percent of residents live below the poverty level. In the 2017-2018 school year, 89 fewer students were enrolled at the district compared to the previous school year, resulting in a corresponding cut to pre-student funding from the state. That’s on top of a local tax lull in Commerce ISD’s general fund, which has seen a shortfall of $185,000 compared to 2013-14 levels.

“We’re like every other rural school district out there, you know — we’re struggling with funding,” said Superintendent Charlie Alderman. “That’s why we had to reach out to the university to build other relationships and maximize the resources we have.”

Texas is ranked 36th in the nation in per-student funding. In 2011, the Legislature cut $5.4 billion from the public education budget, a move that prompted more than 500 school districts to sue the state (the Texas Supreme Court later ruled that the state’s school finance system is broken but constitutional). During the last legislative session, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and state senators watered down a House plan to inject $1.8 billion into the public education system and repair outdated funding formulas.

Other small, rural Texas districts, under myriad financial pressures, have considered cutting services or consolidating. Among other problems, they’ve seen a shrinking state funding stream, teacher recruitment woes and fluctuating property values when oil prices nosedive. Comstock ISD, 30 miles northwest of Del Rio, has cut extracurriculars like football, band and agriculture to keep the doors open. The Panhandle’s Kelton ISD is trying to cut costs, too, which is why the superintendent does double duty as the school principal.

But in that atmosphere of austerity, Commerce ISD, with Texas A&M’s help, has been able to launch the ASPIRE program, along with establishing a choir program and a prep academy to get area high school kids into college classes. “The only problem now is that we’ve got so much interest in the [choir] program that I’ve got to find a way to add more classes. But that’s a good problem to have,” Alderman said.

Commerce isn’t the only rural Texas district asking universities for help in lieu of adequate, reliable funding.

Take Premont ISD, a perennially failing South Texas district that partially credits Texas A&M University-Kingsville for its dramatic turnaround. After five years of low state test scores, the district partnered with the university and finally met academic requirements in 2016, staving off the district’s potential closure. In April, Victoria ISD approved a contract with the University of Houston to manage two of its struggling schools, though the idea was eventually swatted down by the state because the contract wasn’t inked on time. Also in April, the University of Texas announced that five of its schools — including campuses in the Rio Grande Valley and Tyler — would share their resources to give nearby districts a leg up.

The state’s universities generally aren’t funding local school districts per se. Rather, they’re putting on staff trainings, helping struggling students learn math and reading, and lending space for district activities on their campuses. These partnerships may become even more prevalent if a 2017 state law allowing struggling schools to hook up with universities to avoid state sanctions gets off the ground.

“We’re like every other rural school district out there, you know — we’re struggling with funding.”

In Commerce, the partnership is mutually beneficial for Texas A&M, since the university may one day enroll these students — who otherwise might not have considered pursuing a degree at all.

“Even being in the same town, we had some students … especially the low-socioeconomic kids … they never got exposed to the university,” Alderman said. “We have kids that have never driven across Lake Ray Hubbard, the one you drive across before you get to Rockwall. They drive across that lake and think it’s an ocean because they’ve never left Commerce.”

The ASPIRE summer program is only in its second year, but Alderman says that STAAR test results “do show improvement” after the program’s inaugural year. With the Legislature reluctant to give schools a much-needed funding boost, Commerce ISD may have to lean on the university even more heavily in the future. “We’re helping each other out,” Alderman said. “We have incredible kids here, amazing students. I want every kid to have the opportunity to do whatever they’re passionate about.”