Santa Ana’s Last Stand?

Wildlife biologist Ken Merritt lost his job trying to save the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge a decade ago. Now the “jewel” of the national wildlife refuge system is under threat again.

Ken Merritt, 65, knows what it’s like to stand between a threatened wildlife habitat and a border wall. In 2007, the Bush administration wanted to construct an 18-foot wall through the federally protected wildlife refuges in the lower Rio Grande Valley that Merritt managed for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). When it fell to Merritt to sign off on an environmental assessment for the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, he refused — an act of conscience that cost him his job.

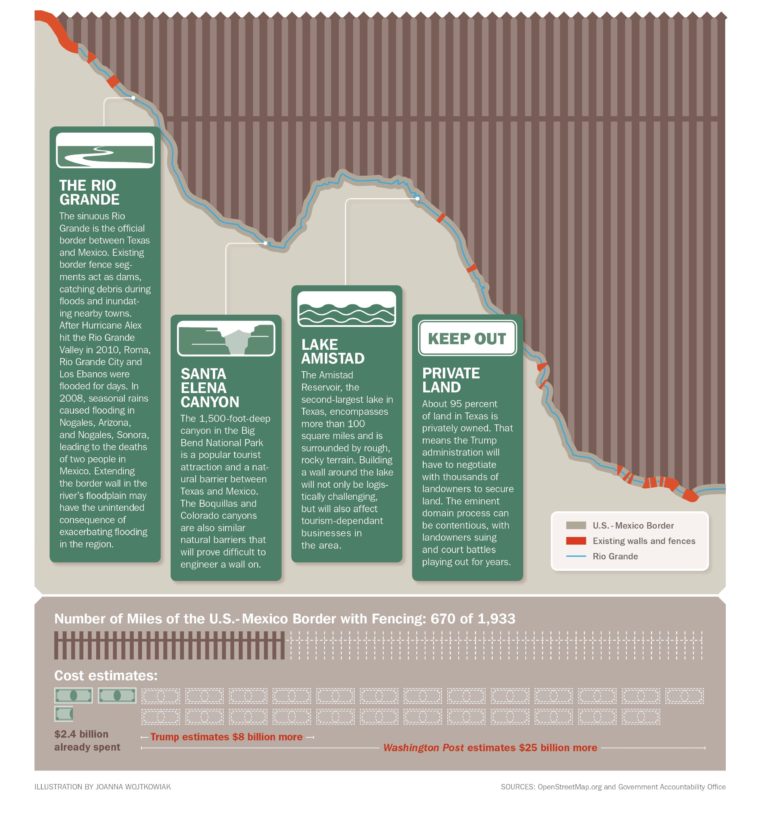

When I reported in late July that the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge was once again under threat, I was reminded of Merritt and the hard lessons he learned about how federal bureaucracies laid the groundwork for the more than 670 miles of border wall built during the last decade.

After Merritt left USFWS, several segments of wall were built through tracts that he’d formerly managed. But the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge — the most-visited and well-known refuge in the Rio Grande Valley — was left unscathed largely because the Department of Homeland Security ran out of funding and the Obama administration was less willing to wall off a wildlife refuge. But now President Trump is anxious to make good on his signature campaign promise of building a “big, beautiful wall” and Santa Ana is in his crosshairs. Can the refuge survive?

Merritt who still lives in the Rio Grande Valley and now works for the Texas Department of Transportation, said federal wildlife managers trying to save what’s left of the region’s threatened habitat have largely been silenced in the name of border security. He keeps in touch with a few of his former colleagues and friends who work in the wildlife corridor along the Rio Grande.

“They’re all really bummed out,” Merritt said. “And it seems like it’s a done deal to all of the folks I’ve spoken with. But of course they can’t say anything or they’ll lose their jobs.”

Merritt is keenly aware he’s an example to others of what can happen when someone in his position speaks out. As the refuge manager, he was required under federal law to fill out a “compatibility determination” to assess whether a border wall would adhere with the agency’s mission to protect and preserve wildlife habitat. In his view, a border wall would have done serious damage. In good conscience, he says, he couldn’t sign off on the project. He’d devoted 31 years to wildlife preservation. And now he was being asked to sign off on its destruction. “It’s not just the wall,” he said. “There’s also the cleared border enforcement zone around the wall, the roads and the light towers.”

As a result of his refusal, private contractors couldn’t enter the refuge to begin surveying for the wall. Merritt thought that his agency would back him up. Instead, his boss, Benjamin Tuggle, regional director of USFWS, told Merritt he’d made a “career-ending decision.” (Tuggle denied telling Merritt that his decision would end his career.)

Today, refuge managers don’t have the option to object. After Merritt left USFWS, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued two waivers in April 2008 that allowed the agency to bypass 36 federal laws, including the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires the compatibility determination from federal refuge managers.

DHS can issue the waivers because of a 2005 law that allows the DHS secretary to bypass federal law in the name of national security. The Trump administration is now invoking that same authority. On August 1, DHS issued a waiver to expedite the construction of 14 miles of border barriers and roads in San Diego, California.

Merritt expects that DHS will soon do the same for Texas.

At Santa Ana, an 18-foot concrete and steel wall would slice through the 2,088-acre refuge, separating the visitors center from the walking trails, observation tower and wetlands.

“A little refuge like Santa Ana just can’t take a blow like that and still be functional,” Merritt said. “Of all places to put the wall, Santa Ana seems like the worst.”

It’s also unnecessary, he said. The Border Patrol already has its own office at the refuge and is allowed open access. And there’s also the underreported fact that undocumented border crossings are the lowest they’ve been in 17 years.

Merritt said that when he was assigned to manage Santa Ana in 1997, he couldn’t believe his luck. But over the years, running a refuge on an international border grew stressful. “The work became more and more politicized,” he said. “There was always something going on with oil and gas or border issues like the wall. We were responding to congressional inquiries it seemed like on a weekly basis.”

In the Rio Grande Valley, 95 percent of the native habitat has been lost to development or agriculture. Over the last four decades, the federal government assembled a string of refuges along the Rio Grande, purchasing and restoring 100 tracts of land totalling 180,000 acres. This intermittent green strand represents the last bulwark against near-total loss of habitat. “Santa Ana is a special place,” Merritt said. “It’s a picture of what wildlife used to be like in the Rio Grande Valley.”

It’s also one of the most biodiverse refuges in the United States and home to the endangered ocelot and the jaguarundi. Because of its subtropical climate, it hosts 400 bird species and 450 different types of plant species, many of which aren’t found anywhere else in the United States.

“You’ll find birds there from Mexico and Central America and when a sighting is publicized on social media, birders come from all over the country to see them,” he said.

At just over 2,000 acres, Santa Ana is small for a federally protected refuge but it has an outsized influence. The refuge draws birders from around the world, and it also hosts youth programs and educational tours for schoolchildren.

Merritt more or less raised his four daughters there. “We used to go there on weekends, even though I’d just finished working there all week,” he said. “We’d walk the trails, see what’s on the ponds or go up on the observation deck to see more birds.”

“The real tragedy is for future generations,” Merritt said. “I don’t know how viable the wildlife corridor is anymore. Can it still exist? I have my doubts.”