SCOTUS Takes Up Texas Abortion Case as Activists Gather to ‘Stop the Sham’

If upheld, the Texas law could set the stage for a wave of similar anti-abortion restrictions across the country.

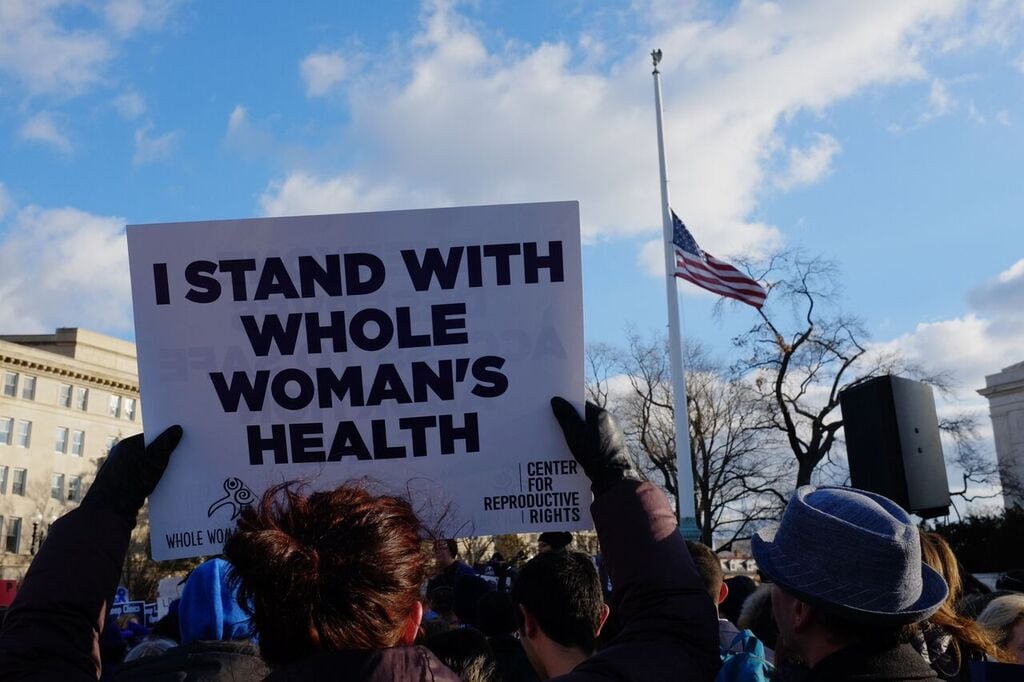

For more than an hour on Wednesday, U.S. Supreme Court justices jockeyed with attorneys over the constitutionality of Texas’ omnibus anti-abortion law, House Bill 2. Meanwhile outside the building, hundreds of protesters gathered for a morning-long #StopTheSham rally, calling for an end to the restrictions.

Texas abortion providers argued the law places an undue burden on abortion providers and patients, while attorneys for the state of Texas defended its regulations as constitutionally sound, and medically necessary, restrictions on legal abortion.

Early in the 75-minute hearing, Justice Anthony Kennedy wondered aloud whether the justices should send the case back to a lower court to gather more evidence of HB 2’s effects on abortion access in Texas.

“Would it be, A, proper, or B, helpful, for this court to remand for further findings on clinic capacity?” he asked.

His comment was a brief clue into the mindset of a judge considered a critical but so far inscrutable voice in this benchmark case, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. The Supreme Court’s ruling is expected to affect whether, or to what extent, state lawmakers can pass abortion restrictions across the country for years to come.

Independent Texas abortion providers have challenged two of HB 2’s main provisions: the requirement that abortion-providing doctors have admitting privileges and the mandate that abortion facilities operate as hospital-like ambulatory surgical centers. At Wednesday’s hearing, attorneys from the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR), which represents Texas providers, and attorneys for the state of Texas answered judges’ questions concerning whether HB 2 had decreased access to legal abortion, as well whether the restrictions were medically justified.

Absent the conservative late Justice Antonin Scalia, known for his colorful questioning, Justice Samuel Alito led a 20-minute interrogation of CRR attorney Stephanie Toti.

Toti told the court that since the law’s passage, more than half of Texas’ abortion clinics have closed. Alito quickly interjected, asserting that the abortion provider plaintiffs had not presented strong enough evidence proving the closures to be a direct result of HB 2.

“There is little evidence [in the record] with respect to why clinics closed,” Alito said to Toti, just minutes into her argument.

She countered saying that prior to HB 2, the number of abortion providers in Texas had “remained stable.” Then, eight clinics closed in mid-2013 in anticipation of being unable to comply with HB 2’s admitting privileges requirement and another 11 closed once the law took effect in September of that year.

Still, Alito wasn’t convinced.

“We’re not talking about a large number,” Alito said. “I don’t understand why you wouldn’t have put in the record evidence as to why each particular clinic closed.”

Chief Justice John Roberts echoed Alito’s skepticism, pressing Toti on whether clinic closures and HB 2’s restrictions were truly “related.”

Justice Elena Kagan, a liberal voice on the court, interjected to bolster Toti’s argument, pointing out that when HB 2’s ambulatory surgical center requirement took effect in late 2014, another 12 clinics closed immediately, and then reopened weeks later after a last-minute Supreme Court intervention.

“It’s almost like a perfect controlled experiment as to the effect of the law, isn’t it?” Kagan told her colleagues. “It’s like, you put the law into effect, 12 clinics closed. You take the law out of effect, they reopen.”

Attorneys and abortion rights advocates see the Hellerstedt case as an opportunity to clarify the “undue burden” legal standard established in 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Another key element of the case concerns what kind of medical justification, if any, lawmakers must cite when passing abortion restrictions.

Major medical groups, including the American Medical Association and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have declared the two HB 2 provisions challenged in Hellerstedt to be medically unnecessary. Still, the state of Texas has maintained they are necessary to protect the health and safety of patients.

But left-leaning justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Stephen Breyer peppered Texas Solicitor General Scott Keller with questions about the medical justification for such restrictions.

Ginsburg pressed him on Texas’ argument that women living in west Texas, which has one remaining abortion facility, can simply cross into New Mexico for an abortion.

“New Mexico doesn’t have an ASC requirement, and it doesn’t have [the] admitting privileges [requirement],” she said. “If that’s alright for women in the El Paso area, why isn’t it alright for the rest of women?”

Keller replied: “Texas obviously can’t tell New Mexico how to regulate,” and the technicalities of geography didn’t have any bearing on the case. “In any event,” he continued, “over 90 percent of Texas women of reproductive age live within 150 miles of an open clinic as of today.”

Keller then pointed to former Pennsylvania abortion provider Kermit Gosnell — who in 2013 was convicted of the murder of one of his patients and three “infants born alive” — as a legitimate basis for implementing the more stringent abortion regulations contained in HB 2. Kagan, however, pointed out that Gosnell’s clinic hadn’t been inspected by the state of Pennsylvania in years. Texas law, she reminded Keller, requires frequent and random inspections of abortion providers.

“Texas’ own regulations actually have made abortion facilities such that that can never happen, because you have continual inspections, to your credit,” Kagan said. “So that was not really a problem in Texas, having a kind of rogue outfit like that. Texas has taken actions to prevent that.”

Sotomayor questioned an exception to the law’s requirements, carved out by the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals last summer, that enables one Rio Grande Valley doctor to continue performing abortions at the Whole Woman’s Health clinic in McAllen. The facility remains the only abortion clinic south of San Antonio.

“Why does [the McAllen doctor] have to become an indentured slave to ensure that women in her area are provided with their fundamental right to choose?” she asked. Keller responded by saying that other doctors could bring forth individual challenges to the law in the future, enabling them to perform abortions if individually approved to do so by the courts.

Before, during, and after oral arguments inside the courtroom, hundreds of abortion rights advocates rallied outside the building, calling for an end to HB 2 and HB 2-style restrictions, which have increased nationwide over the last several years. Activists from Texas, and across the country, traveled to Washington for the historic case, many standing in line for hours in hopes of getting a seat inside the courtroom. They wore purple and orange t-shirts, outnumbering the dozens of light blue-clad anti-abortion protesters that gathered early in the morning.

“It was already beyond hard to get an abortion in Texas,” said Lindsay Rodriguez, communications director of the National Network of Abortion Funds, who traveled from Texas to Washington for today’s rally. “HB 2 has further devastated abortion care in Texas, but we’re fed up. We’re furious, we’re powerful, and we’re not going back.”

Amy Hagstrom Miller, president and CEO of plaintiffs Whole Woman’s Health, said in a statement after the hearing that her organization is not just fighting for Texas women, but for all women in the United States.

“Today we stood up for the woman from Lubbock who will drive over 250 miles one way to end her pregnancy,” she said. “We stood up for the mom from Laredo who will look through her cabinets, hoping to find something that will end her own pregnancy because she can’t afford the travel, the child care or the multiple days off work that have become part of getting an abortion in Texas.”

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.