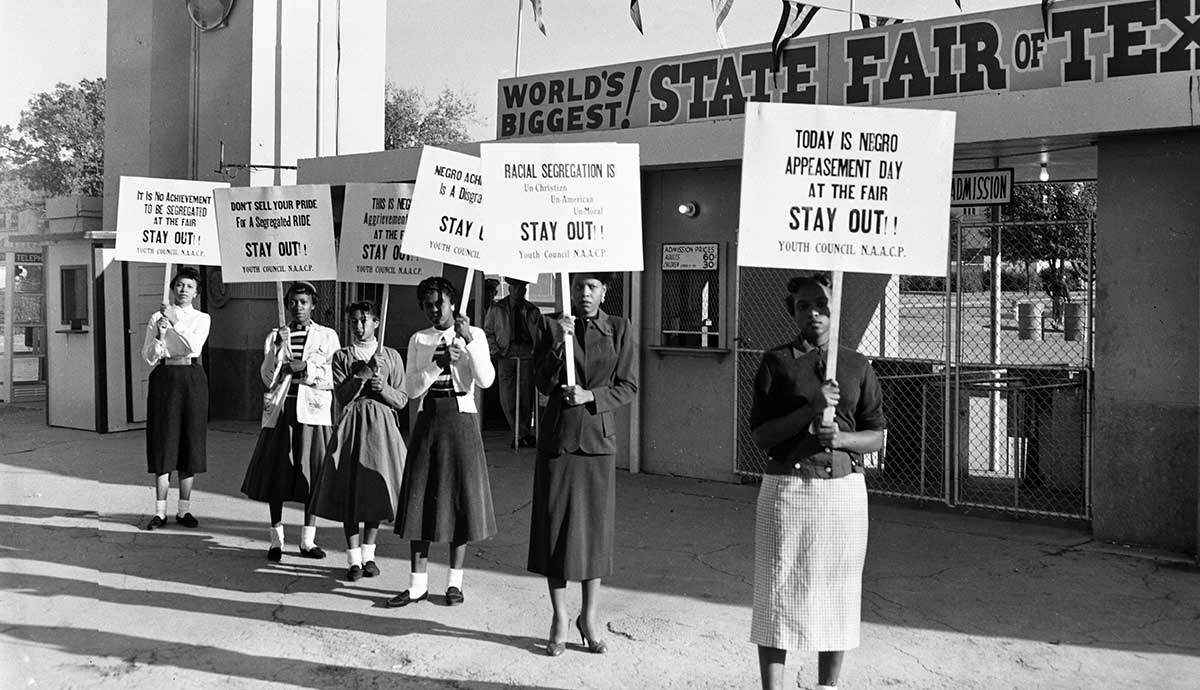

Segregation Texas Style

A version of this story ran in the April 2015 issue.

We Texans are a tribal bunch with a strong state identity. We also are defined by a unique brand of disunion. Our culture of exclusion explains why Texas metro areas—San Antonio, Dallas, Houston and Austin topping the list—are among the nation’s more economically and educationally segregated.

In these cities, the wealthy have walled off themselves from the working class, and educated professionals rarely share a neighborhood sidewalk with laborers, according to a study by the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto. “It is not just that divide in America has grown wider,” writes urban theorist Richard Florida. “It’s that the rich and poor effectively occupy different worlds, even when they live in the same cities and metros.”

In 2014, the state’s demographer put it plainly: Latinos have lower educational levels and are less represented in high-skilled occupations than other groups.

But the Texas brand of segregation not only divides, it defines the contours of a Texas identity. What distinguishes Texas segregation from, say, New York City, where I lived for many years, is a Texas identity that was born fighting against “the Mexican.” Remember the Alamo! At the same time, Texas segregation allows the two worlds to join in the embrace of cultural appropriation, which explains why some equate “Texas Mexican” not with people deeply rooted in the state, but with a salted mug, a sizzling platter and a bowl of queso.

Our cities and streets reflect the unique interdependence of two worlds, side by side. In Remembering the Alamo, Richard Flores describes San Antonio’s historic downtown streets as a contrast between “the new, the modern, the American … while the old, the traditional, the Mexican is dissolved into the folkloric, the quaint, the foreign.”

It shouldn’t come as a surprise then that a fraternity at the University of Texas at Austin recently hosted a “Border Patrol”-themed party, ostensibly inspired by tales of the Old West. When partygoers donned sombreros, draped their shoulders with serapes or dressed as construction workers, they were reflecting back to us the segregated world they inhabit, one in which Mexicans and U.S.-born Latinos occupy low-paying jobs and serve an ornamental role.

Apart from its cultural weight, the entrenchment of Texas segregation served an economic purpose, fueling the expansion of the farming industry of the early 20th century, when Mexicans picked cotton on white-owned fields. “Race ideas…also provided a basis for control of the Mexican, a critical element for the stability of the new farm order wrote David Montejano in Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986.

Fifty years ago, President Lyndon B. Johnson invoked the Texas social order in his address to Congress after the civil rights march in Selma, Alabama. His intimate experience with the misshapen hand of segregation, he said, began while teaching at a Mexican-American school in Texas: “Somehow you never forget what poverty and hatred can do when you see its scars on the hopeful face of a young child.”

Decades later, the tech industry has become an economic engine and, like cotton farming, it reflects a segregated social order with Latinos mainly occupying the rungs of laborers—cleaning offices and serving up breakfast tacos—while the farms of the new Texas economy largely belong to whites.

That’s the most insidious part of segregation, the obliviousness to it.

That’s the most insidious part of segregation, the obliviousness to it. Simply consider the much-celebrated coming-of-age film Boyhood. The story tracks 12 years of a white family’s life in Central Texas, in which we see them at school, at work, and playing with friends—somehow completely without any encounters with Latinos, except for one with the “help.”