Short Story Finalist: ‘Oblivious’

“Whether it was one protest or the other it felt good to get the anger out. They had plenty to be pissed about, after all.”

Years from now, fiction writers will grapple with how to approach 2020 in the United States. With two very long months remaining, we’re still enduring a raging pandemic we should’ve tamed months ago, against which backdrop we’ve undergone a summer of racial-justice protest, countered by futuristically militarized stormtroopers let loose to “dominate” the protesters; a rapid escalation in the effort to undermine, from without and within, our election process; and the specter of creeping fascism, which is emboldening hate groups and far-right militias and domestic terrorists. And the worst! Is yet! To COME!

So, good luck covering 2020 in one novel.

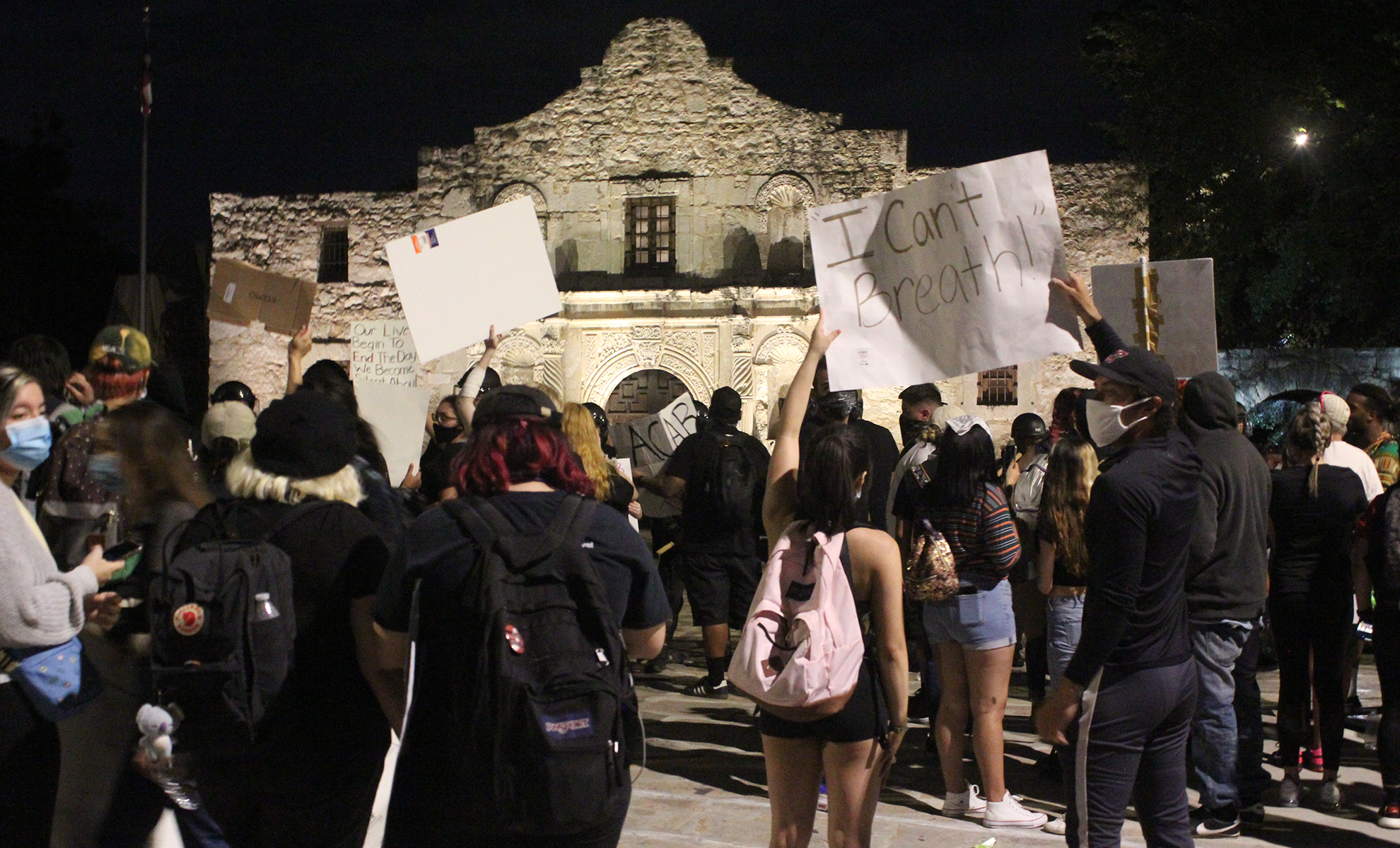

In “Oblivious,” Rudy Ruiz tries to cover it in one short story, and given the confines of our short story contest’s 2,500-word limit, he does an excellent job. While the virus sweeps through Texas, an attorney splashes around in family gore; a young couple turns inward to battle what they consider to be the real threat—garden pests; and teens Yankee and El Chulo learn to stand up against inequality while all around them, the people, “in the hospitals with ’Rona or in the streets with police officers’ knees on their chests, they couldn’t breathe.” —David Duhr, fiction editor

*

Outside, it was snowing crepe myrtle blossoms. Floating on the 105-degree breeze they possessed the advantage of not being as vulnerable as wintertime condensation. From my air-conditioned perspective in the dining room, gazing out onto the front lawn through the arched windows, the scene played like a Bollywood movie.

I stepped outdoors to stand in the surreal pink blizzard. Spherical topiaries blanketed with blooms resembled puffs of cotton candy. The manicured grass was a polka-dotted carpet.

Down the street, I could hear sirens approaching, a dissonant, rising chorus heralding an onslaught of diverse vehicles speeding towards my general location at varying distances. Doppler effect. Terrell Hills. Texas.

*

’Rona was raging through San Antonio, just like it was ripping through the rest of Texas and the South. It was like ’Rona had done had enough of New York and all those liberal pansies hiding out in New England and had come down to do some real fighting, face-to-face, with people brave enough to take it on sans a mask, people packing heat in public, people with a license to die. In Houston, ’Rona acted like one of them hurricanes that swept through the Gulf Coast every couple of years with increasing violence. In places like Corpus Christi and the Rio Grande Valley, it was flooding hospitals not with the murky E. coli-infested water that Rita brought to the Texas Medical Center but with patients unable to breathe. Refrigerated trucks were being repurposed to act as morgues, storing bodies instead of produce. Ambulances piled up single file, red lights flashing, at the ERs, like the lines that used to snarl the narrow streets down by Brownsville’s Gateway Bridge before the border was closed, but now they were trading not in goods, but in lives. At the same time, the New York Times reported that six million people had signed up for food stamps since the start of the pandemic, and Chevron started buying oil and gas assets at fire-sale prices, paying $5 billion for Houston-based Noble Energy. The people, though, in the hospitals with ’Rona or in the streets with police officers’ knees on their chests, they couldn’t breathe.

*

El Chulo and Yankee didn’t like ’Rona one bit.

“She’s a bitch!” El Chulo yelled as they rode their bikes up Broadway from downtown S.A.

He couldn’t believe they’d had to wear masks at the Black Lives Matter protest.

“At least we got to take them off for spray-painting the Christopher Columbus statue, ese!” Yankee called back, pedaling so fast, his long black hair whipped in the wind.

They hadn’t worn masks, per se. They wore black bandanas, which they kept wrapped loosely around their necks. In a way, they kind of liked wearing them, but they wouldn’t admit that even to each other. The bandanas made them feel like bandidos, like they were throwbacks to the days of the Old West, like something interesting and wild and chaotic might actually happen in their lives for a change, and especially after forty-five days of self-imposed confinement in their respective abuelas’ houses on the West Side.

They weren’t particularly invested in BLM. They weren’t that sure what was so bad about Columbus either.

“El vato killed all the Indians,” El Chulo had explained, putting a can of red paint in Yankee’s hand.

“Asshole,” Yankee muttered, spritzing the old dead bronze dude in the face.

But in general, whether it was one protest or the other it felt good to get the anger out. They had plenty to be pissed about, after all. Pinche remote learning when they didn’t even have broadband at home. Pinche income inequality. Might as well skip the rest of high school, get a GED and start delivering for Instacart like their older buddy Ronny. Ronny had invited them to Terrell Hills to drop off a big order from Central Market at one of the gringo mansions there, and it might as well have been Beverly Hills when they saw it.

“Is that a frickin’ museum?” El Chulo had asked Ronny, who had a year of community college under his belt, thus positioning him as the expert.

“No, man. That’s a frickin’ house. Guy used to be CEO of Valero and General Motors. Nice guy. Big tipper,” Ronny pontificated.

GED. Instacart. El Chulo and Yankee had nodded at each other, smiling slyly as they helped unload the bags and place them by the wrought iron gate so that the homeowner’s uniformed servant could retrieve them, sanitize them, and stock them in the stainless steel SubZero.

El Chulo and Yankee had agreed they had to come back to Terrell Hills and get up to some good old-fashioned venganza at some point. And so they did. It seemed fitting that after getting riled up at the BLM peaceful protest and defacing the Columbus statue, they work their way up to some real retribution.

El Chulo carried several cans of lighter fluid in his backpack. Yankee was in charge of transporting the beer.

*

I stared at the bugambilia plant in my backyard. A week earlier it had looked lush with new growth, heavy fuchsia blooms hung from the tips of its long vines. But now it looked stressed out, like something had gotten to it. The leaves were battered and torn; some looked liked they’d literally been snacked on by something.

I had my hands on my hips and a look of befuddlement on my face when my wife asked, “Did you look under the leaves?”

“No. Why would I do that?” Needless to say, I’m not a landscaping professional, not a horticulturalist.

“To look for bugs?” she replied.

“Ah, yes, of course.” I flipped a leaf over and then leapt back upon seeing four tiny orange things clinging to its underside. “What the…?”

“Take a picture,” she said.

Nowadays, we take pictures of everything. Sometimes, when the TV goes into sleep mode and starts streaming one of our picture rolls, there’s a strange shit show. Everything from last summer vacation to ’Rona survival shopping lists to pictures of foster kittens that have helped us survive the four months of quarantine. Now we can add the picture of the tiny orange wormlike creatures obliterating our bugambilia.

“They’re worms,” I said. “Gross.”

“Zoom in.”

I swept my fingers across the screen and almost jumped back again in surprise. “They’re not worms. They have huge legs. They look like insects.”

“That’s because they are insects.”

A couple Google minutes later, we had learned all about leaf footer bugs in their nymph state. Who knew? Apparently, our bugambilia.

She came out of the garage with a spray bottle and a bandana. “Wear this when you spray it.”

*

Bobby simply couldn’t take it any more. He figured they’d lived long enough. And the longer they kept living, the more slowly he felt he was dying. So, after much careful consideration, he decided to just do it. He found his father’s treasured long knife, the one he used to filet the fish he caught on his trips to Port Aransas. It was supremely sharp. In fact, his father had once boasted it was better than what most sushi chefs used. The blade entered his father’s chest cavity with surprising ease. His mom was a bit more agile, especially for an eighty-year-old. In the fracas, chasing her across their well-appointed salon, he’d managed to nick himself on the forearm. While he paused to unleash a torrent of obscenities not typically allowed in that “no-no” room, she managed to lock herself in her bedroom and dial 911.

“My son’s lost his mind,” she gasped. “He killed my husband and he’s coming after me.”

He kicked her door open the way they used to do in the TV show COPS before it was cancelled due to its glorification of police brutality. (Thank you, BLM.) Then he got her good for all those times she’d put him in his place over the previous fifty-odd years. The police were on the way and his arm was going numb. He hadn’t made a plan beyond the patricide and matricide phase, so he sat out on the curb waiting for the cops to arrive. He wore a mask just to be safe. Wouldn’t want to catch COVID from a pig. As Bobby sat there, he couldn’t help but admire the two ornate pots to either side, crowned with bright red geraniums. He could smell their fresh aroma. His parents had been mean motherfuckers and hadn’t known a lick about how to raise a child without damaging him to the core, but they’d sure known how to maintain an impeccable garden.

*

Inside the wooden carport, an antique Jaguar gleamed in racing green.

“That’s a sweet ride,” Yankee whispered. “Maybe we should try to steal it before we burn the place down.”

“Nah, ese,” El Chulo replied, dousing it with lighter fluid, squeezing the can as if it were a bottle of Whataburger ketchup. It made that reverse gulping sound as it swallowed air and spit out its aromatic liquid, splashing over the shiny paint job. “This car is too conspicuous, man. The cops would be on us in a flash. Terrell Hills P.D. has the fastest response time in the state of Texas. We got to get out of here fast.”

Yankee nodded. “That’s a big word, ese.”

“Conspicuous,” they both mouthed, chuckling as they squirted the wooden pillars supporting the carport.

After a brief argument over who would get to strike the match, they agreed to both do one at the same time.

The place went up in a hurry, a cloud of hot gas repelling them out onto the side street.

They drained their beers hastily, jumped on their bikes, pulled their bandanas tight over the bottom half of their faces in case there were any security video cameras around, and sped back towards Broadway, laughing out loud.

“Down with the establishment!” shouted El Chulo.

“Fuck ’em!” Yankee agreed, turning to admire the Fortune 500 CEO’s mansion as they whizzed by. Someday he’d be somebody, he thought. He’d deliver Instacart groceries to that wrought iron gate and get a big fat digital tip in his app without ever meeting the man face-to-face.

*

When my wife came out front to meet me for our evening walk, I showed her the pink crepe myrtle blossoms flaked all over the round shrubs. I was proud, as if I’d had something to do with it, even though all I did was notice it. She wasn’t as impressed as I was, made me feel like I’d been tripping on the LSD I never I took. Maybe it was the ’Rona monotony that had made it all seem so spectacular. I shrugged as we walked towards the now stationary sirens and the flashing lights a block away.

A masked man cradled his head, sitting in handcuffs between two picture-perfect red geraniums. He was flanked by police officers wearing riot gear. Did they now use those face shields all the time to protect themselves from the ’Rona? The man looked like an attorney, not a criminal. But it turned out he was actually both. My wife read he stabbed his octogenarian parents to death in the house he’d grown up in, right here in Terrell Hills. I didn’t think crime could really come here. I thought it was something reserved for other neighborhoods and distant cities where people rioted on TV. I guess I was sorely deluded.

We turned the corner after passing a parking lot’s worth of fire trucks and police cars lining the streets. But we couldn’t take our usual route because someone had torched a garage. A couple of days later, when we finally did get to inspect the damage, we noticed two things. First, the Trump-Pence yard sign that had punctuated the front lawn since 2016 was conspicuously absent. Second, the main structure of the house, designed by a semi-famous Texas architect, had thankfully escaped unscathed.

“We can lose people to the ’Rona,” I said, “but not award-winning architecture.”

My wife knit her eyebrows together disapprovingly, but she didn’t say anything. Ever since the quarantine, we had to learn to pick our battles more carefully. Her mom had nearly died from COVID-19 just a few weeks earlier. I guess it was too soon.

When we arrived back home, the sun had set and the crazy summer heat was backing down. A semi-merciful breeze rustled through the palm trees. The cicadas shuddered in waves like a choir of rattlesnakes lurking in the trees. I checked on the bugambilia again. As I turned a leaf, the tiny cluster of orange leaf footer bugs moved in unison, hiding on the flip side. Google taught me that too. Apparently, they move together like a family unit when they’re in their infant state. It’s almost cute. Almost. I sprayed them, watching their movements come to an abrupt stop as their small, wormlike shapes curled up and detached from the leaves, disappearing into the grass below.

“I wonder if they even know what hit them?” I asked my wife.

“Probably not. I wonder if that’s what is happening to us humans when there’s a huge plague like this Coronavirus killing hundreds of thousands of people across the planet?”

As I stored the bug killer and opened a bottle of wine, I replied, “You mean, like, is some unseen entity spraying us with COVID-19 to get us under control?”

“Yes, like instead of insecticide… humanicide.”

Sitting silently by the pool as the last blush of light seeped from the sky, we swirled our glasses of cool Chardonnay. We both stared at each other for a while and then agreed, “Nah.”

If you or someone you know needs help, call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

Rudy Ruiz on writing “Oblivious”:

I wanted to write a story driven by reflections on the bizarre and surreal time we have been living through in 2020: COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, the presidential election. All combined, I am sure most of us feel that we are in a very strange, chaotic, emotionally charged era. I wondered how oblivious many of us might be to the causes of our social plight, to how we are self-destructing as a people. If we can’t face and unite against systemic racism, health inequities, income inequality, and climate change, what hope does our nation—or our world—have for the future? How sustainable are we as a society? And, in the end, might there be forces at work—natural, spiritual, or otherwise—that could come to see all of humanity as a pest or a parasite not worthy of our planet unless we change our course?

Read more from the Observer:

-

Claiming Major Superfund ‘Success,’ Trump EPA Focused on Completing Cleanups, Not Climate Planning: As work stalled on hardening Superfund sites against climate-related weather extremes, budget cuts continued and a backlog of sites awaiting cleanup ballooned.

-

Houston, Let People Walk: When forced to choose between cars and people, the fourth-largest city in the United States has a long history of siding with the former.

-

Democrats Seek to Undo San Antonio Senate Slip-up: Or, Roland’s Revenge.