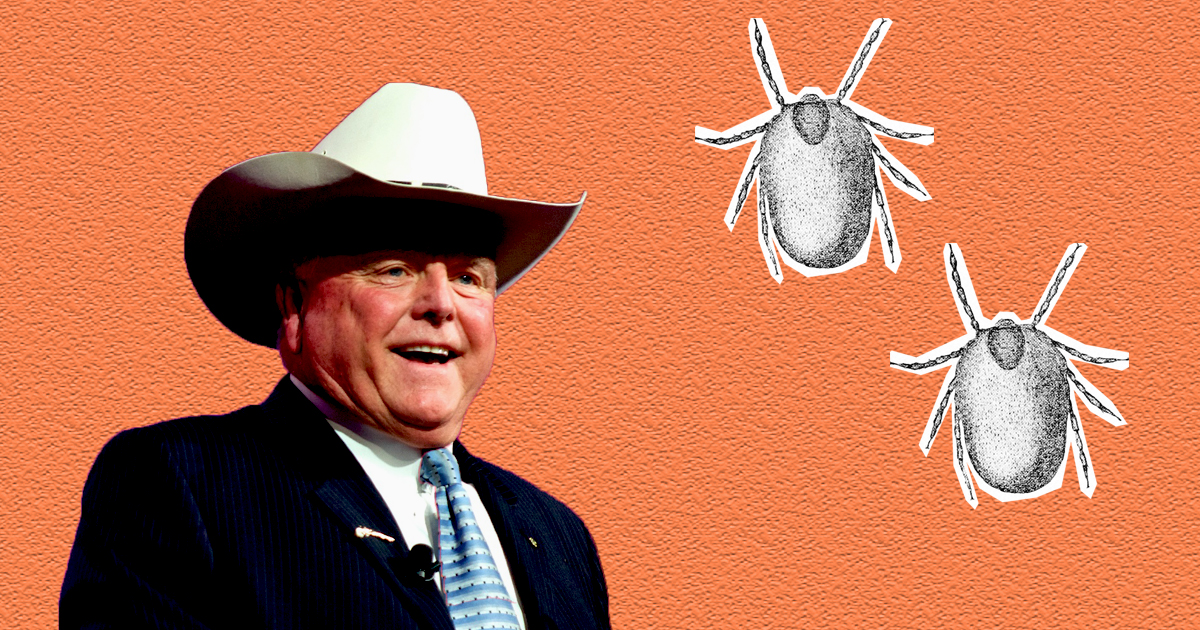

Sid Miller’s Ag Department Knew About Dangerous Pesticide Violations in 2015, Did Nothing for Two Years

A state inspector found that USDA's fever tick teams broke state and federal rules by indiscriminately spraying poison and dumping toxic pesticides on ranchland.

On August 17, 2015, Harlingen rancher Danny Davis called in a complaint to the Texas Department of Agriculture (TDA). Like many others who raise cattle and horses near the U.S.-Mexico border, Davis was caught in the state-federal fever tick dragnet — a mandatory program in which South Texas ranchers must allow their animals to be treated with insecticide to kill a deadly tick before they can be sold. Davis told the state regulatory agency that after U.S. Department of Agriculture employees doused seven of his calves in Bayer’s Co-Ral, two of the animals died. He suspected the USDA had used the chemicals incorrectly and wanted the state ag agency to investigate.

It turned out Davis was on to something. In December 2015, a TDA inspector found that USDA pesticide applicators had violated state and federal pesticide laws hundreds of times while applying chemicals to kill the tick, which can carry a disease that causes anemia and death in cattle. The inspector couldn’t prove that Co-Ral was killing cattle, but he did unearth a trove of broken rules. Among his findings: Federal employees failed to keep complete records of pesticide treatments; didn’t always wear protective gear when handling and mixing toxic chemicals; didn’t adequately warn workers about the stout pesticides they’d be handling; indiscriminately sprayed a poison that a federal judge has since instructed the EPA to ban; and regularly dumped Co-Ral onto South Texas ranchlands in violation of the chemical’s label instructions.

All told, Inspector Arturo De La Garza’s investigation implicated 17 USDA employees and revealed an agency culture defined by the regular misuse of highly toxic pesticides in the name of killing ticks.

De La Garza signed and dated his damning 81-page report on December 15, 2015. But Sid Miller’s agriculture department did nothing for two and a half years before finally issuing violations and warnings to wrongdoers in April 2018. What took so long? “The delay in finalizing the agency actions on this issue is solely due to understaffing” of attorneys in the agency’s enforcement division, said Mark Loeffler, a department spokesperson.

It’s not the first time TDA attorneys have sat on completed investigations into pesticide misuse for an inexplicably long time. In May 2017, department investigators wrapped up a yearlong investigation into a massive pesticide drift case in a tiny Panhandle farming community, where 40 residents complained that chemicals sprayed by crop dusters were killing crops and making them sick. The investigator in that case identified the culprit — a local pilot — but almost a year later, the agency still hadn’t taken action. TDA attorney Jessica Escobar said at the time that “we were not happy with how long it took” to close the case.

Ultimately, nearly three years after the initial complaint, the TDA doled out a grand total of $4,600 in fines in the fever tick investigation. The biggest penalty — totaling $3,000 — went to Michael Spellane, a USDA supervisor who admitted it was agency practice to simply dump the remainder of Co-Ral mixture from fever tick “spray boxes” onto the ground when an application was complete. Eric Christensen, a rancher whose South Texas land was the site of some of the dumping, told De La Garza that he felt pressured by USDA employees. The feds had reportedly threatened to charge Christensen with a misdemeanor if he didn’t let them treat his cattle, so he figured they’d take action against him if he didn’t let them dump the chemicals, too, he said. Christensen told the Observer on Tuesday that he hadn’t seen negative environmental effects from the dumping. But two workers at Riata Cattle Company in Lasara told De La Garza that they’d seen dead birds where Co-Ral had been dumped.

“The delay in finalizing the agency actions on this issue is solely due to understaffing.”

Rene Munoz IV, a USDA employee, was fined $1,600 for dumping Co-Ral on the ground. He received a mere warning for, among other transgressions, indiscriminately spraying the insecticide chlorpyrifos on vehicles and trailers used in fever tick operations for the purpose of “cleaning and disinfecting” them. Chlorpyrifos’ label forbids use on “any sites that come in contact with livestock.” The chemical is so dangerous that in 2000, the U.S Environmental Protection Agency barred it from household use. This August, a federal judge ordered the EPA to ban it completely, citing health concerns (Trump’s USDA disagreed). Munoz did the same type of spraying with Co-Ral, also in violation of that chemical’s label, records show.

The USDA pesticide applicators did not return calls for comment, and USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service officials had not answered a list of questions by press time.

In July 2018, Ag Commissioner Miller made the unusual decision to personally inspect a fever tick spray box operation in Raymondville, temporarily shutting it down along with 15 other spraying sites throughout South Texas. He said the personnel operating the boxes — claustrophobic metal rectangles through which cattle and horses run single-file before being doused with Co-Ral for five seconds — were breaking rules by applying the insecticide in a confined, unventilated space. The agency then employed a bit of political theater, putting out a press release bragging that “here in Texas we’re going to [treat cattle for ticks] according to the law.” After Miller’s regulatory counterparts at the EPA, USDA and Texas Animal Health Commission never showed for a meeting to discuss the matter, he took a shot at them, posting a photo of a roomful of empty chairs.

But the 2015 investigation shows that the TDA had concrete evidence of pesticide misuse in fever tick applications for years before Miller rode down to Raymondville with a burr under his saddle. So why did TDA make a spectacle of momentarily shutting down spray boxes this summer? Loeffler, the agency spokesperson, said Miller was prompted by reports ranchers sent to the TDA this year claiming that pesticide applications had killed their cattle. (One of those reports was made by Davis, the same complainant in the 2015 case that prompted the investigation; the other came from a rancher in Zapata County.)

Loeffler said the stalled 2015 probe didn’t factor into Miller’s actions this year, despite the fact that both scenarios involved the misuse of Co-Ral by pesticide applicators. If Miller had paid attention to the 2015 report prepared by De La Garza, he would have seen that the inspector noted “the spray box is a ‘confined, non-ventilated area,’” thus possibly disqualifying it from being used in Co-Ral applications. This week, Miller began allowing ranchers to bypass spray boxes in favor of a less intensive “hand-spraying” procedure. The agency also proposed a rule to require Co-Ral be sprayed in a ventilated area.

Despite the fact that TDA’s investigation into Davis’ complaint took years to close — and though Miller’s subsequent actions smack of political theater and ignorance of his own agency’s investigations — Davis said he isn’t ticked off at the ag commissioner. At least he’s doing something to help ranchers, he said: “So far Miller is the one that does what is right by the law.”