Julio “Alex” Zuniga ends the messages he sends from his prison cell with the signoff “Solidarity forever.” He sometimes includes a postscript with music recommendations, leaning toward vibey alt-pop and indie—a somewhat surprising mix for the self-described anarchist activist. He prefers to be called Alex, but many of his contacts inside and outside of prison know him as “Comrade Z.”

He’s the man people who have been at the Memorial Unit (formerly called Darrington), a 1,610-bed state prison in southeast Texas, point to when asked about organizing on the inside. Like everyone else locked up in Texas who is physically and mentally able, Zuniga, a 44-year-old from San Antonio, was required to work without pay while housed at Memorial, near the unincorporated town of Rosharon, from 2018 to 2023. He tended livestock and labored in the agricultural fields, where he’d cut weeds and harvest carrots, cabbages, and onions. Before these fields were owned by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ), they were plantation land worked by slaves.

While he grew up on the South Side of San Antonio, Zuniga spent some of his youth in the rural outskirts of Laredo. This was the extent of his previous exposure to agriculture, but he took to farmwork somewhat easily. “I love animals, and I love playing with dirt,” he told the Texas Observer in a March interview.

But, as he began reading about the history of the land he was working and its roots in slavery—and as he learned more about labor movements—he started advocating for himself. He would occasionally refuse to work, telling officers he wouldn’t return to the fields until he received requested safety gear like boots and masks. He’d get slapped with a disciplinary case—prison policy says that anyone who refuses to work can lose visitation privileges, be confined to their cell, or receive other punishments that can affect their chances of parole. Zuniga is currently about 11 years into a 15-year sentence.

In the end, though, Zuniga said that pushing back would usually get him the things he asked for.

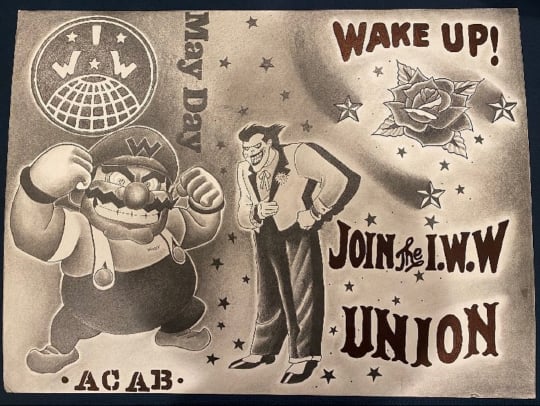

In 2019, he became involved with the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC), a prisoner-led arm of the 119-year-old labor union the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). “Sometimes they say it’s illegal [for prisoners to unionize], but it’s not,” Zuniga said. “It’s just frowned upon. But it works.”

Incarcerated workers are not considered “employees” under federal or state law, and they lack protections guaranteed to other workers—including the right to organize and collectively bargain under the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. That New Deal-era act of Congress is the bedrock legal safeguard for free-world workers who take collective action to improve their terms of employment, but its protection stops at the prison door. Further, incarcerated laborers lack the right to file an Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) complaint, and they generally cannot sue over job-related discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. Absent these protections, organizers must get creative when pushing for things like pay for incarcerated workers and recognition as employees.

Zuniga’s organizing efforts—which include appearing on podcasts and writing articles, attempting to organize collective work stoppages, and developing relationships with staff to address problems like bug infestations—were bolstered by IWOC’s unincarcerated members, including Courtney Montoya.

Based in New Mexico, Montoya works with prisoners nationwide but said she often hears from Texans about being forced to work while sick or in unbearable heat. TDCJ does not track which work areas are air-conditioned, but many job assignments, including agriculture and maintenance, take place at least partially outside, where workers are subjected to increasingly hotter average annual temperatures.

“[Connecting with labor organizers] provides folks with that lifeline,” Montoya told the Observer. “There’s somebody watching. There’s somebody out there. It’s not just for the person, but it’s also to signal to the [prison] administration that there’s eyes on this.”

According to TDCJ data, 2,323 prisoners were injured on the job in 2023, more than half in food service. That figure is likely incomplete, as prisoners say they often receive disciplinary cases if they report injuries, so they’re less likely to report on-the-job accidents.

Amanda Hernandez, director of communications for TDCJ, told the Observer that officials do not punish prisoners for reporting work injuries. “However, inmates who do not follow proper safety and security procedures may receive disciplinary action,” she wrote in an email.

In 1865, the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery—except as punishment for a crime. This legally permits Texas to force the incarcerated, including more than 40,000 people convicted of nonviolent crimes, to work for no pay under threat of punishment. Texas is one of only seven states that takes advantage of this free forced labor.

Hernandez told the Observer that the agency follows medical staff’s recommendations if someone is hurt, but several currently incarcerated Texans said they received job assignments contrary to medical restrictions or were punished or ignored when too ill or injured to work.

Jamon Hestand, who’s currently incarcerated at the Robertson Unit, a 3,000-bed lockup in Abilene, told the Observer it’s “hard as hell” to get dismissed from work because of a disability or medical condition.

Since 2021, at least 240 work-related complaints have been filed by incarcerated Texans to the Office of the Independent Ombudsman, according to public records obtained and analyzed by the Observer. The ombudsman office reports directly to the chairman of the Texas Board of Criminal Justice, TDCJ’s politically appointed oversight board. (Prisoners, employees, and the public can use the ombudsman to request non-criminal investigations or log official grievances.) The most common reason for work-related complaints is being medically unable to work but being forced to do so, according to the records. Other common reasons were harassment, retaliation, or lack of proper equipment.

While TDCJ keeps general statistics on work-related injuries, the same isn’t true for deaths. Although the agency reports all in-custody deaths to the state attorney general’s office, it is not required to say whether any deaths were due to work-related injuries, including heatstroke. The agency doesn’t even track this internally. In an email response to a public information request, a representative with the TDCJ Office of the General Counsel wrote, “Because of the variety of factors that may lead to death, TDCJ does not track [job-related deaths] in this way. We do not capture that particular metric in our reports.”

The Observer found multiple reports on in-custody deaths that mentioned work assignments in public records released by TDCJ over the last 20 years, but most reports gave little detail and were unclear about whether the death was work-related. According to a heavily redacted autopsy report released by TDCJ, 41-year-old Michael Wagley died in August 2016 from injuries sustained when the tractor he was using for his job on the farm at the Beto Unit in East Texas rolled on top of him. In 2005, an incarcerated maintenance worker at the Ramsey Unit in Rosharon died after being electrocuted by a live wire. In 2009, two prisoners working on a water line in Huntsville were electrocuted. One died of his injuries. And in December 2021 58-year-old Ronald Lake died of heart disease, TDCJ officials reported, four hours after being allowed to leave his work assignment at Ramsey.

Over the past decade, organizations like IWOC have helped empower people inside prisons to seek better conditions, including the right to be paid and to refuse work. At the same time, outside support for incarcerated workers has increased among legal scholars and advocates, who have sued prisons and fought for legal protections.

In recent years, several states have passed constitutional amendments to outlaw slavery as punishment for a crime—Colorado in 2018; Utah and Nebraska in 2020; and Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont in 2022. Similar amendments are on the ballot in California and Nevada this November. (For Texas to join these states, a supermajority of the GOP-dominated Legislature would be required, followed by voter approval.) These pushes have been the result of outside advocacy groups, prison organizers, and legislator buy-in.

Prison unions don’t function like most others. Rather than having strict membership status and dues, IWOC primarily distributes information on how to organize, and its outside “locals”—in more than a dozen states, Washington, D.C., and the United Kingdom—answer questions from and advocate for prisoners. Membership is free for prisoners. Because of this loose structure, it’s unclear how many incarcerated Texans consider themselves members, but IWOC founding member Brianna Peril told the Observer there are “thousands of people [in prisons] around the United States who have read the materials and the literature and who feel like they are members of the IWW.” She said incarcerated workers take ideas “and just run with it.”

Because of the unique relationship between incarcerated workers and their quasi-employer, prisoners lack contracts or any legal mechanism for collectively bargaining. “The absence of unions, or collective bargaining more generally, contributes to the exploitation of prisoner-workers by amplifying the imbalance in the labor-management power dynamic,” wrote Katherine Leung, an attorney with the National Labor Relations Board, in a 2018 article in the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review.

Incarcerated workers also have no right to picket or distribute flyers to gain public support. What they more often do, at the risk of racking up parole-threatening disciplinary actions, is strike.

IWOC has backed some of the largest prisoner-led labor strikes in history. In 2016, incarcerated workers from multiple states withheld their labor to honor the 45th anniversary of the historic 1971 Attica Prison uprising—the bloody demonstration during which prisoners took control of the New York facility to fight for better conditions, calling for an end to modern-day slavery. After cellphone footage of the 2016 strike leaked, the U.S. Department of Justice conducted an investigation and published a report on living conditions and violence in Alabama’s prisons. Similar strikes took place in 2018 and 2023 in various states, including Texas.

This December, IWOC, along with Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, another national collective involving prisoner activists based in Pennsylvania, is calling for a weeklong work stoppage in prisons nationwide to coincide with outside demonstrations calling for an end to the 13th Amendment’s exception clause. Jailhouse Lawyers Speak is offering assistance to prisoners who face retaliation for participating.

Zuniga said he faced severe punishment for his organizing efforts, spending much of his time at the Memorial Unit in solitary confinement. He said he was assigned to work in the fields while he was in solitary, even though TDCJ policy states people on that security level cannot work. He eventually appealed to the prison ombudsman to get a unit change and was transferred in 2023 to the agriculture-focused Ramsey Unit nearby.

“I think it was worth the risk,” Zuniga said. “But in the end, I had to pay the price.”

Incarcerated workers in the United States have been striking for as long as there have been prisons. People at the Walnut Street Prison, established in Pennsylvania in the late 18th century, would hold “Blue Mondays”—so named in reference to workers’ general malaise at the start of the week—during which they would stop work, lay down their tools, and demand better conditions. After the Civil War, prisoner strikes helped stir up public outcry around convict leasing, the practice of hiring out incarcerated workers to private contractors used in Texas and many other states.

The handiwork of Texas prisoners is visible in the state’s most iconic building, as incarcerated laborers quarried the pink granite used to build the current Capitol, dedicated in 1888. Union stonecutters, fearing the effect of prison labor on free-world wages, refused to work for a time on the construction project.

Historically, prison organizing has come in waves: after World War II, during the 1960s and ’70s, and over the past decade. Still, those unions can be easily stamped out by prison officials. Some states, not including Texas, have laws against prison strikes. When asked whether TDCJ allows prison unions to meet, Hernandez told the Observer, “There are no inmate union meetings held inside TDCJ.”

“It was worth the risk. But in the end, I had to pay the price.”

In 1977, the Supreme Court ruled in Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union that incarcerated workers don’t have an explicit constitutional right to unionize. The court left it up to prison administrators to decide, based on their opinions of how dangerous unions might be.

In a dissent, Justice Thurgood Marshall noted that the court had previously made strides toward protecting incarcerated people’s rights and this was a step back. “The decision today is an aberration, a manifestation of the extent to which the very phrase ‘prisoner union’ is threatening to those holding traditional conceptions of the nature of penal institutions,” Marshall wrote.

In the immediate aftermath, many legal scholars argued that prison unions could be an important tool for rehabilitation and that prison officials should be given less deference. Some pushed back against the idea that prison unions would be dangerous, with social scholar Stephen Woolpert issuing “a relatively benign prognosis of unionization’s impact on the performance of correctional institutions.”

The Jones ruling was a blow to prison labor organizing, but it didn’t entirely shut the door on “groups like the IWOC who wish to pick up the mantle of inmate labor organizing today,” wrote legal rights scholar Keith Armstrong in 2020.

IWOC is not the first group to attempt to unionize Texas prisoners in the modern era. The Texas Prison Labor Union was founded in 1995. Its aim, as described in 1998 by the Prison Legal News, a magazine produced by the nonprofit Human Rights Defense Center, was to “organize Texas prisoners and their supporters into a single body to promote social justice, human rights, and workers’ rights.” The union, funded by member dues and donations, distributed a flier with updates on lawsuits against the prison system, helped connect prisoners with researchers, and provided other resources (including a booklet of Tai Chi exercises). As recently as 2023, people describing themselves as members of the union have contacted legislators calling for pay for prisoners.

In July 2014, IWOC minted its statement of purpose, which is to build solidarity among incarcerated and nonincarcerated workers and to support “those engaging in collective action or who put their own lives at risk to improve the conditions of all.”

Peril, the IWOC founding member, told the Observer that previously no nationwide union had “really tied together and pushed forward ideas about how having prison slavery as a competing labor force undermines everyone’s conditions in the workplace.”

In 2019, Weldon Thompson worked as a plumber at the Garza East Unit, a small men’s prison near Beeville. While locked up, he had been trained and stationed in the unit’s maintenance shop. In February of that year, a maintenance supervisor ordered Thompson to weld wheels onto the base of a commercial deep fryer in order to make it moveable, a task that was outside of his job description and beyond his training. But, he “went on and welded the wheels to avoid getting in trouble,” according to a lawsuit filed by Thompson against TDCJ and the supervisor. The supervisor who gave the order didn’t stick around to oversee the work.

When he was finished, Thompson and another man tried to move the massive fryer. That’s when pieces of the appliance fell onto Thompson’s hand, pinning and crushing it. His right pinky finger was fractured and his middle finger was smashed, requiring nine stitches to close the wound, according to the lawsuit. He underwent surgery to fix it about a week later, but the pinky finger ended up being amputated. He also suffered nerve damage to his right wrist.

Given the injuries to his hand, prison officials allegedly told Thompson he’d be exempt from work—he’d be what’s known as “medically unassigned,” the court records say. But, according to the lawsuit, he continued to be assigned work and received multiple disciplinary cases for telling officials he was supposed to be exempted.

Thompson’s lawsuit, filed in 2019, is one of at least eight active state and federal suits against TDCJ regarding improper training or equipment and other unsafe working conditions. Another suit, filed in 2023, alleges that officials at the Powledge Unit in Palestine forced metal fabrication shop workers to use tools with incompatible attachments.

In July 2021, Jose Medina was using a grinder when an improper attachment “exploded into his face shield causing high-velocity projectiles to lacerate his face and mouth,” per the 2023 suit. In a 2019 lawsuit, a prisoner at the 2,130-bed Gib Lewis Unit in East Texas describes getting injured after slipping and falling while working in the kitchen. He had informed officials numerous times that there were no rubber steel-toe boots in his size, which would protect against slick floors, before he was injured, the lawsuit says.

Taking the prison system to court can be a route to obtain better working conditions, but it’s difficult to win a case. The 1995 federal Prison Litigation Reform Act limited incarcerated workers’ rights to sue by requiring them to exhaust multiple steps in a grievance process first. Often, personal injury lawsuits apply only to individual workers, so court-ordered improvements wouldn’t necessarily improve overall conditions.

By and large, prisoners who can’t sue or organize lack control over their working conditions, cannot refuse potentially hazardous tasks, and have little or no recourse after being injured. TDCJ has its own policies that purport to protect workers, but they’re often ineffective, according to critics and prisoner lawsuits.

Hernandez, the TDCJ spokesperson, told the Observer via email, “All inmates and employees are required to complete safety training related to their job assignments,” all workers get appropriate personal protective equipment, and each unit has an OSHA-certified risk manager who performs weekly and monthly inspections.

Despite the often dangerous conditions, many incarcerated workers value their jobs, saying they would opt in even if the work requirement fell away. But when accidents happen, even the happiest worker can become frustrated with the lack of protections.

Stephanie Barron received a certificate in 2022 that showed she had completed her on-the-job training to work as an electrician at the Murray Unit in Gatesville. The following year, she was assigned to the maintenance department. She told the Observer she loves her job and working in general; she “prefers to be productive” and is not involved in any prison organizing.

“I have been fortunate to have good working conditions for the majority of my incarceration,” Barron said. “Offenders in food service have much poorer conditions. I have truly been blessed not to have had that job for a long period of time.”

But, in April, she went with a different boss than usual to inspect generators, which are checked weekly to make sure they’ll kick in during a power outage. While walking along the side of a generator, Barron slipped into a tire well, slamming her knee and popping it out of joint. She fell only two or three feet, but the damage was severe enough that she couldn’t walk. The supervisor with her alerted medical personnel, who eventually called 911.

It was the first time Barron had been seriously injured on the job. She had torn ligaments and fractured her leg. When she spoke with the Observer in mid-May, weeks after the accident, the only medical treatment she had received was a 30-day prescription for a high dose of ibuprofen. She was given a brace, crutches, and temporary access to a wheelchair, but her requests for something to elevate her leg were ignored until she eventually filed a grievance. And she waited weeks for an MRI.

“That is the extent of ‘medical care,’” she told the Observer. In late July, she wrote to say she was finally going into surgery, three months after her injury.

While incarcerated workers sometimes turn to grievances, unions, or the legal system to effect change from the inside, outside advocates are pushing to change how the law treats imprisoned laborers.

Savannah Eldrige, a co-founder of the Coalition to Abolish Slavery-Texas, was part of the successful 2022 push to change the Alabama constitution to abolish forced prison labor. Similar efforts in Texas have been unsuccessful. In 2019, sympathetic state representatives filed legislation to pay incarcerated workers; the bill got a hearing but died in committee. In 2021 and 2023, state Senator Borris Miles and Representative Alma Allen, both Black Houston Democrats, proposed constitutional amendments to prohibit slavery as punishment for a crime, but none of these measures received a hearing. Eldrige said the movement has gotten “little to no response” from most lawmakers.

Eldrige’s coalition is part of a larger, nationwide coalition known as the Abolish Slavery National Network. While the goal is to end slavery state by state, each venue provides its own challenges and therefore needs its own playbook, organizers say.

In Texas, Eldrige says this means focusing on raising public awareness—speaking on panels, commissioning murals, appearing on podcasts. “The first part is to get heard, and I don’t think that the bill will be heard if we can’t reach more people,” she said.

On the federal level, Democratic Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey has introduced bills that aim to recognize incarcerated workers as employees under the law and give them at least some of the same protections and privileges as workers outside, including fair wages and OSHA protections. “The current state of prison labor in America is inhumane and unacceptable,” Booker said in a statement in February.

Although slow-moving, these legislative efforts give inside activists hope that things could change someday. Hestand, the incarcerated man at the Robertson prison, told the Observer that organizing inside is difficult. “We can’t do without legitimate outside help,” he wrote.

Texans organizing inside prisons, in the absence of meaningful legal protections, say it can be disheartening to push for change against the all-powerful prison system.

Even Alex Zuniga has had to take a break from organizing. He stepped away from union organizing in 2023 after his friend and fellow IWOC member died in prison and he and other organizers were separated by releases and unit changes. He remembers writing to state Representative Carl Sherman, a DeSoto Democrat, saying: “I lost this battle. They tore us all apart, they broke us all up. It’s over … so how do I go back to being a prisoner?”

In March, he told the Observer he’d become tired of being an adversary to the system and was focusing on his upcoming parole hearing and studying for his GED exam. He’s a talented artist, able to create photo-realistic portraits with a No. 2 pencil, so he spent some time honing his craft.

“I’m super scared, but it’s natural I guess,” he wrote in a hopeful letter after that parole interview. “I’m ready to start living again, I’m ready to begin giving back to the community, and live for helping others. Lately, I’ve been struggling with my living area, it’s so loud all the time. But I just keep trying, and pushing for a better outcome soon.” When he got out, he said he wanted to be part of a Christian ministry in Dallas headed by Sherman.

On April 26, the TDCJ Board of Pardons and Paroles rejected Zuniga’s request for release. Instead of immediate freedom, he’d have to serve another four-and-a-half years.

On April 30, Zuniga wrote to the Observer, saying in light of that result he was going to contact IWOC about getting involved again. “This will help sustain me for the remainder of my time,” he wrote. “I gotta look out for what’s best for me now. … It’s not about trying to make parole anymore, but doing something with meaning, with love, with camaraderie.”

Staff Writer Josephine Lee contributed to this report.