I.

“I find myself every day searching for things I’ve lost.

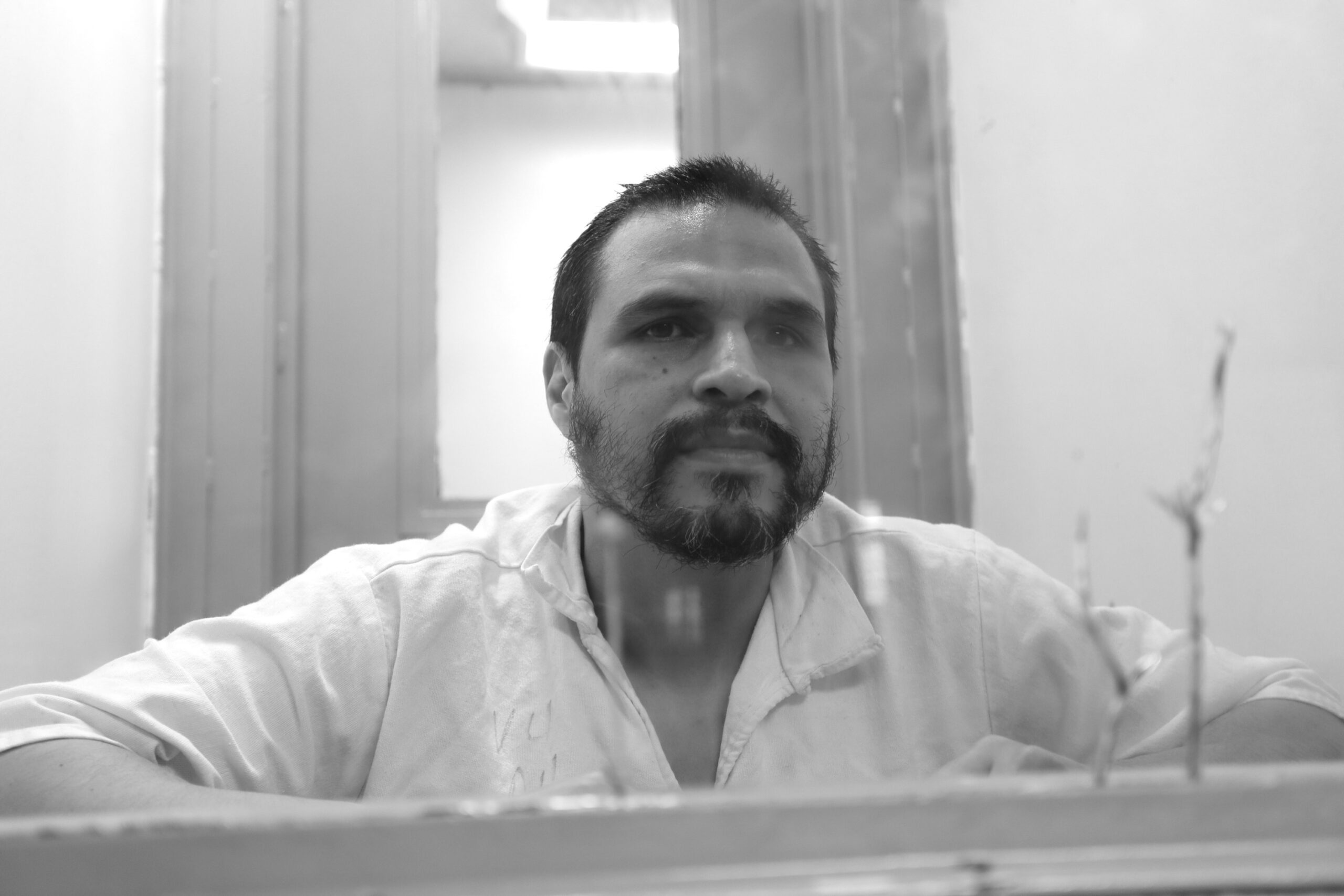

Roger Uvalle, held in solitary confinement for the past 26 years by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Three years ago, guards came to Roger Uvalle’s cell to tell him he was “catching chain”—being shackled and transferred to another prison. As the guards escorted him to the chain bus with about 60 other inmates, Uvalle began trembling, overcome by anxiety. He turned so pale another prisoner told him he looked like a ghost. He didn’t relax until guards put him in his new solitary confinement cell, a 6-by-10-foot space where he’d spend 22 to 24 hours each day, alone, just as he had every day for the past two-plus decades.

Years of almost no human contact have warped Uvalle’s sense of time. Weeks, months, even years blend together. He says his memory has degraded to the point where he now struggles to keep track of the few personal items he’s allowed to have. He sometimes spends hours turning over his cell looking for stamps, letters, art supplies.

His recollection of the time before 1992, when he went to prison for two armed robberies, is hazy. He knows he spent time in state hospitals; that his family struggled to find him mental health care growing up in San Antonio; and that as a teenager, he once tried to kill himself by swallowing a bottle of Valium. He knows that he was self-medicating on a cocktail of booze and whatever drugs he could find at the time. He knows that when he first went to prison, he was housed with the rest of the general inmate population and received mental health treatment, which he says helped.

And he knows that about 12 months into his 40-year sentence, guards sent him to solitary confinement after they accused him of being involved in back-to-back fights and hiding a makeshift knife in his cell. Two years later, while he was still in isolation, guards accused him of being affiliated with the Mexican Mafia prison gang, a scarlet letter officials use to justify keeping people in solitary.

About five years in, Uvalle says, he stopped getting medication for his mental illness, started hallucinating, and then struggled to keep himself and his cell clean. “I couldn’t care for myself and didn’t care about much and was experiencing psychotic behavior on a regular basis,” he wrote in a letter to me. When I visited him in prison recently, he talked about his most recent hunger strike, his third in the past two years. He had refused food for seven days before giving up this time. “Most of the time, they don’t acknowledge your hunger strike if you don’t have outside help,” Uvalle says. “They’ll let you die right there. They don’t care.” It reminds me of a line from one of the letters he sent me before our visit, when he described how some inmates set fires in protest. “There’s fires literally every day,” he wrote. “Never been in a place where there are fires every day.”

During our conversation, Uvalle seems shaken to be speaking with a stranger. His slow, soft speech hardly carries through the buzzy closed-circuit phone that connects us through the cracked plexiglass pane. He tells me he’s worried he’s getting worse. He’s struggling again to keep himself and his cell clean. He cries randomly sometimes, but doesn’t know why.

Uvalle went into solitary confinement in 1993, when he was 21 years old. Now, at 47, he’s been in solitary for 26 years—more than half his life.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) has one of the country’s largest inmate populations in solitary confinement. This is due, in part, to the sheer size of the Texas prison system, the largest of any state. At last count, TDCJ held more than 4,400 of its 145,000 prisoners in “restrictive housing,” a euphemism for solitary, where inmates live isolated in a small cell for at least 22 hours every day.

Texas also holds more prisoners in long-term solitary confinement than every other state and the federal prison system combined, according to a report by the Association of State Correctional Administrators and the Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law at Yale University. At last count, according to TDCJ, about 1,300 Texas prisoners had been in isolation for six years or longer. More than 680 had been in solitary between six and 10 years, 450 between 10 and 20 years, and 129 between 20 and 30 years. Eighteen Texas prisoners have been in solitary for more than 30 years—living in isolation since at least 1990, when George H.W. Bush was still president.

Activists, families of inmates, and formerly incarcerated people call solitary one of the most damaging and dehumanizing practices that has endured in an opaque prison system. For years, they have pointed to the effects of solitary—delusional thinking, violent outbursts, hallucinations, and, in some cases, suicide—when asking state lawmakers to create an independent body to monitor the state’s prisons. They say independent oversight, a solution implemented when Texas’ juvenile lockups came under scrutiny more than a decade ago, could help administrators, politicians, and the public flag problems before they mushroom into tragedies.

Long-term solitary continues because of the courts’ hands-off approach to prisons, with judges and inmates hamstrung by a 1996 law that makes it more difficult to challenge conditions in lockup. Reforms have proved difficult at the state level, in part because the Legislature seems unaware of what’s really happening behind bars. At a 2019 legislative committee hearing, an expert testified about the effects of long-term solitary confinement and said prisoners are sometimes held for decades in isolation; lawmakers were floored at her statement and questioned whether Texas inmates really spend that long in solitary.

Jeremy Desel, a spokesperson for TDCJ, calls Texas a “leader” when it comes to reducing solitary. According to the agency, the total number of prisoners in isolation has dropped from more than 9,000 about a decade ago to around 4,400 this year.

Over the past decade, TDCJ has implemented several programs aimed at moving people out of isolation, part of a national shift away from solitary. The change is driven by a growing consensus among mental health experts and corrections officials that solitary is not only expensive ($61.63 a day per person versus $42.46 in the general prison population), but also harmful for inmates, staff, and the communities that people damaged by isolation return to. But as the Texas Tribune reported last year, some of TDCJ’s new programs may actually mask the extent to which the state has reformed its solitary confinement practices. Inmates moved out of solitary and into a mental health diversion program still live in conditions that seem indistinguishable from solitary; prisoners continue to be confined in small spaces and have limited time outside their cells. Regardless of these similarities, Texas doesn’t count its participants as being in isolated housing. (Desel didn’t respond to a long list of questions about the agency’s use of solitary confinement.)

TDCJ also tracks very little about the effects of this extreme practice. After recent reports of isolated prisoners killing themselves or being killed by guards, I asked the agency how often inmates in solitary attempt suicide or get beaten and tear-gassed by officers. The agency could not provide those numbers.

For months, I’ve exchanged letters with more than a dozen prisoners in long-term isolation, trying to understand the effects of this controversial punishment that a growing consensus of medical and mental health professionals equates to torture. Many of these prisoners aren’t sure how—or, in some cases, if—they will ever get out of solitary.

They wrote about paltry to nonexistent mental health care in an environment proven to cause psychological distress. They told me that sick, elderly, or otherwise vulnerable inmates often languish in isolation. Their letters detailed hallucinations and delusional thoughts that test their grip on reality. Sometimes they get lucky and wind up next to people who look out for one another. Sometimes they’re housed next to inmates who throw feces, mutilate themselves, or get gassed by guards. They all say the noise is inescapable. “You hear others talking 24/7,” wrote Dennis Hope, 51, who’s been kept in solitary for more than two decades. “Sometimes they are hollering, arguing, singing, or screaming like they are on fire.”

II.

“They’ve known that ad seg drives people crazy since the 1800s. I can tell you all kinds of stories of those I’ve seen come back here normal and slowly go crazy.”

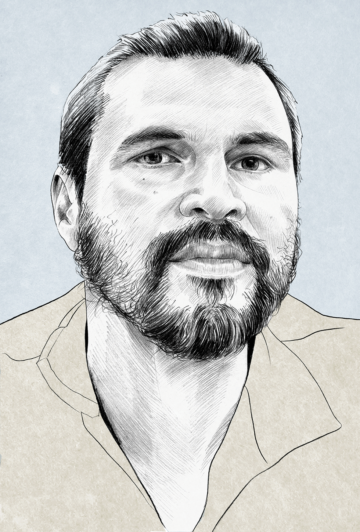

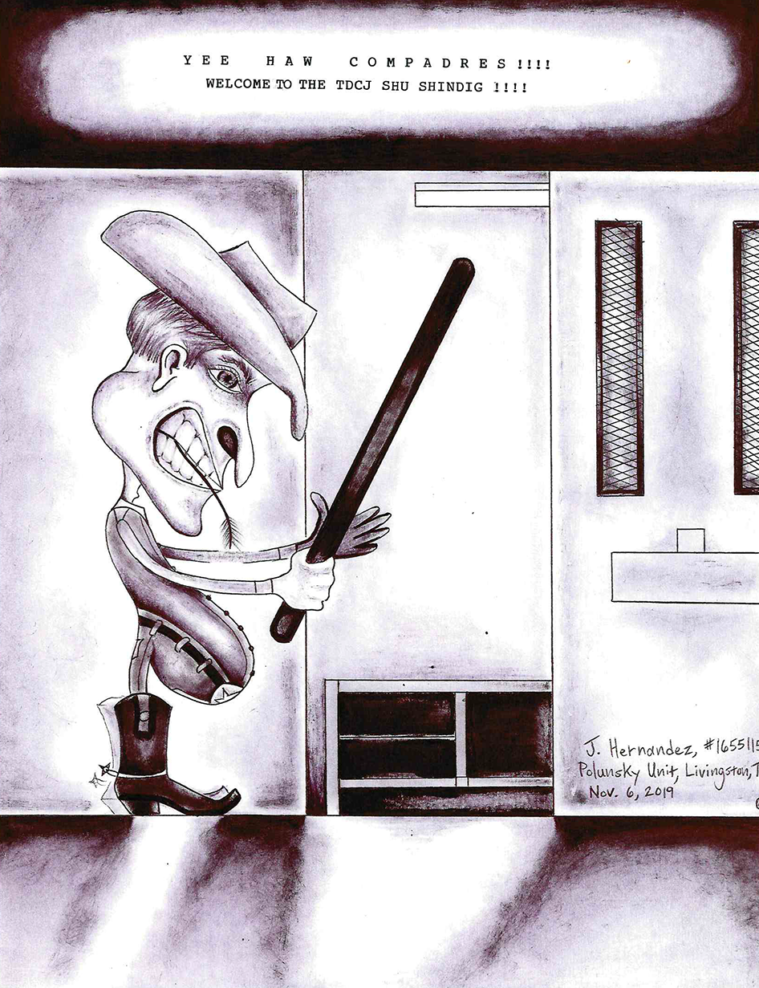

Pedro Hernandez, held in solitary for nine years

Solitary confinement is a uniquely American form of punishment. It began as a misguided attempt at rehabilitation. America’s first prisons, built in the 1800s, housed inmates in near total isolation based on a Quaker belief that solitude fostered penitence and reformation—hence the word “penitentiary.” In reality, foreign attachés dispatched to study American prisons in 1831 were horrified after witnessing a degree of isolation “beyond the strength of man.” Charles Dickens was revolted by what he saw while touring an American penitentiary in 1842, writing, “I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body.” In 1890, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with a prisoner who challenged his placement in solitary for 45 days, stating that inmates subjected to even brief isolation tended to slip into a “semi-fatuous condition” or became violently and irreversibly insane.

By the turn of the century, solitary had mostly gone out of style as a core correctional model in America. But in Texas, as convict leasing and prison farms replaced slavery as the primary tool for black oppression after the Civil War, solitary was still reserved as a severe punishment. Inmates on Texas’ prison plantations were locked in pitch-dark boxes, sometimes for so long or in such great numbers that they suffocated to death. In 1947, Oscar Byron Ellis, who had operated a money-making penal farm in Tennessee, took over the Texas prison system and built a new “segregation unit” in Huntsville to quarantine “hopeless cases.” Under Ellis, the authoritarian control Texas exerted over its prisoners became the model other states tried to emulate. Penologists drooled over what they called the “Texas Control Model.”

Texas’ approach to maintaining order inside its prisons at the time also relied on another method of control. As Texas’ inmate count grew throughout the century, the state squeezed profits out of its prison farms by empowering certain inmate enforcers to keep order rather than hiring more guards. Dubbed “building tenders,” these prisoners became part of a secret but brutal system of extortion, violence, and rape that lawmakers ignored for decades. The violence at the heart of the system came into full view in 1972 due to a lawsuit named after David Ruiz, an inmate who’d been radicalized by his treatment in prison. In a complaint to the federal court in East Texas, Ruiz described being beaten by building tenders, threatened by prison officials, and thrown naked into a dark, freezing solitary cell for so long that he sliced open blood vessels in his forearms just to get out (he was stitched up and promptly thrown back in the hole).

Ruiz’s lawsuit hit the court at just the right time. A new reform-minded judge, aptly named William Wayne Justice, was looking for a test case, troubled by a stream of complaints other Texas prisoners had filed with his court. Ruiz’s petition ultimately became the headlining complaint on a sweeping class-action lawsuit against the Texas prison system. In December 1980, Justice sided with Ruiz and the other inmate plaintiffs, delivering a searing indictment of the Texas control model. “It is impossible for a written opinion to convey the pernicious conditions and the pain and degradation which ordinary inmates suffer within TDC,” the judge wrote. Justice ordered a complete overhaul of the state’s prisons, including dismantling the building tender system and instituting federal court oversight, reforms that Texas fought but was ultimately ordered to make in 1982.

As the state struggled to hire enough guards to monitor Texas’ ballooning prison population, a power vacuum opened up that prison gangs started to fill. The same violence that had been directed at inmates behind the scenes came screaming to the surface, increasingly directed at outnumbered guards who no longer had the protection of inmate enforcers. And so, to regain control, prison administrators reached into the dustbin of history, building a new system of widespread isolation.

Just before Benito Alonzo was released on parole in March 1974, Fred Carrasco approached him in prison at the Walls Unit to see if he wanted to make some money on the outside. Alonzo did, so he gave his phone number to Carrasco, a South Texas drug dealer who ran with a gang that called itself “the Dons.” According to authorities, after Alonzo got out and returned home to San Antonio that summer, someone called and offered him $500 to transport a bag containing pistols to an inmate trustee who worked outside the Huntsville prison. In a statement he later gave to investigators, Alonzo admitted to delivering the bag but claimed he didn’t know what was inside.

The guns eventually made their way inside the Walls Unit to Carrasco and his crew, who took 12 prison staff and four other inmates hostage on July 24, 1974. Carrasco’s 11-day escape attempt, the longest prison siege in American history, ended in a gun battle that killed Carrasco, another gunman, and two hostages. Alonzo was sentenced to life in prison in 1976 for his role in the siege.

Homicides and riots increased in Texas prisons into the early 1980s. Officials struggled to hire enough guards to maintain order; eventually, isolating prisoners with gang connections became standard operating procedure. In 1985, after three inmates were killed in a stabbing involving two prison gangs, the Texas Syndicate and Mexican Mafia, the state’s prison director ordered 17,000 accused gang members confined to their cells—including Alonzo, who’d been labeled a gang affiliate but lived in the general prison population.

More than three decades later, at the age of 84, Alonzo remains in solitary confinement. He regularly needs treatment for hepatitis C, prostate cancer, and heart problems, but says medical appointments are often delayed—if not completely dropped—due to understaffing. Inmates housed near Alonzo have told me they had to shout and bang on their doors to call for medical attention when he’s collapsed in his cell. “Sometimes when you’re back here this long, they forget about you,” Alonzo told me.

In February 2017, Alonzo and five other men living in solitary at the Polunsky Unit in East Texas filed a lawsuit claiming that TDCJ has given them no way out of isolation. The men, all of whom have been in solitary for years or decades due to allegations of gang affiliation, accused TDCJ of running them through an arbitrary classification-and-review process that keeps them indefinitely confined to “inhumane and debilitating” conditions. Some of them, like Alonzo, have been eligible for parole for many years but are unlikely to ever be recommended for release while they remain in solitary.

Over the past decade, TDCJ has offered a gang renunciation and disassociation program as a way for inmates accused of gang affiliation to leave isolation. After landing in solitary, these prisoners are required to spend at least a year going through a screening and “debrief” process to get out.

Jason Hernandez, a prisoner who organized the lawsuit that Alonzo joined, has been eligible for parole on felony theft convictions since 2012 but has been isolated for the better part of a decade due to his alleged gang affiliation. His maximum sentence runs out in March 2022. In a letter he wrote to me this fall, Hernandez said TDCJ’s pathway for him out of isolation forces him to become an informant for the state, which “poses an unreasonable risk to my health and safety.”

“My complaint is that the devastating psychological effects of prolonged solitary confinement causes prisoners significant mental harm and places them at a grave risk of even more future psychological harm,” he wrote.

The isolation of alleged gang members appears to have even further skewed the racial makeup in solitary in Texas. While black and brown inmates account for two-thirds of the state’s prison population, they’re three-fourths of inmates in solitary. Ten of the 12 prison gangs TDCJ identifies as “security threat groups” are black and Latinx. The solitary population is also almost entirely comprised of men; at last count, there were fewer than 100 women in restrictive housing.

After solitary helped Texas prison officials quell the violence of the 1980s, “it seems like we never really went through that next step of figuring out, ‘OK, what can we do now that we’ve gotten control over the situation?’” says Michele Deitch, an expert on prison conditions who teaches at the University of Texas at Austin. Instead, Texas continued to rely on solitary throughout the 1990s to control violence and weather the rise of mass incarceration. “It’s a completely inhumane system we’ve developed,” Deitch says. “It does real damage to the people who are housed in those conditions.”

III.

“Isolation shatters the mind and corrupts the soul, and breeds a darkness that even the light of Jesus Christ struggles to diminish.”

Christopher Guffey, held in solitary for 16 years

If confining a person to years of solitary blurs the line between security and punishment, Texas’ practice of banishing hundreds of prisoners to more than a decade of isolation raises profound questions of retribution versus rehabilitation.

Steven Jay Russell, 62, a con artist who famously escaped four Texas prisons in five years, has been in solitary since his final escape, in 1998. More than two decades of sedentary life in close quarters have given him an impacted spine that makes it difficult to walk. Guards now push him around shackled to a wheelchair whenever he leaves his cell. A committee of prison officials reviews Russell’s placement in solitary twice a year in hearings that he calls pointless, saying they never consider whether he remains a security threat. “Some committee members will tell me there’s nothing they can do for me because they don’t have the authority to release a ‘high-profile offender’ back to population,” Russell told me in a letter.

Dennis Hope, 51, filed a lawsuit in 2018 claiming he’s stuck in solitary because of his escapes more than 20 years ago. Before filing his case, Hope churned through TDCJ’s classification-and-review system for nearly a decade. He says there have been particularly disorienting periods where guards moved him into a new cell every couple weeks. He experiences bouts of depression and hallucinations. He’s lived next to people who hurt or killed themselves. He suspects his eyesight is failing because of decades staring through a crosshatched wire screen that covers the small windows on his cell door. “I have turned over to face a wall and thought I saw a face staring at me,” Hope wrote in a recent letter. “I have thought I heard scratching noises on the wall and thought that somebody on the outside was trying to claw in.”

Christopher Guffey told me the seven years he spent in solitary confinement in Texas prisons before his release in 2008 gave him a hatred for everyone and everything. “While in seg I tried to kill myself multiple times because I couldn’t get any help for the problems I was going through,” he told me in a letter. “I had no one in society that cared and could do anything for me even if they did. My mind was getting darker and darker, and I became extremely violent and hostile towards everyone.” Nine months after his release, Guffey was involved in a kidnapping for which he’s now serving a life sentence. He’s back in solitary.

Pedro Hernandez describes getting what he calls “hot flashes.” He’ll get furious over something small, only to calm down minutes later, feeling silly about his outburst. Hernandez says the rage started after a couple years in isolation. As he approaches a decade in solitary, anxiety and depression have also surfaced, but it’s the flashes of uncontrollable anger that make him feel as though he’s going crazy. “You get so mad you feel like you’re losing it,” Hernandez says.

Juvenile lockup, where Hernandez went after being arrested at 13 for a shooting, is where he got his first taste of solitary. Whenever staff left him in the cell too long, he’d swing his shirt like a lasso to snag the sprinklers and flood his cell. He says that when he got too combative, staff strapped him to a chair on wheels and rolled him around the facility until he calmed down. “I mean, if this affects adults like it does, what do you think happens to a kid?” Hernandez says.

In 2010, two years after Hernandez went to prison on a life sentence for murder, guards accused him of being a gang member and sent him to an administrative segregation cell at the Polunsky Unit. He now spends 22 to 24 hours a day cramped inside a concrete cell with a small, 4-foot horizontal slit in the back wall just inches from the ceiling—his “window.” He has almost no access to vocational or recreational programs and isn’t allowed phone calls, except when there’s a death in the family—at least, that’s the policy. In March, Hernandez’s father died, but he learned about it in a letter a month later, despite a family member calling to tell the prison.

Hernandez has had no human contact for nearly a decade, except for guards who handcuff him whenever he’s taken out of his cell for showers, recreation, or the occasional visit, when he’s placed into a small cage equipped with a closed-circuit phone system connected to the other side of a plexiglass screen. Ramona Rodriguez, Hernandez’s grandmother, tries to visit as often as she can with family members, who help her make the 175-mile drive from Waco. “I’m getting old,” says Rodriguez, who is 72. “I’m afraid I’ll never get to hug him again.” She says her grandson has changed since landing in solitary. His eyes dart around during visits, and sometimes he can’t seem to focus. Other times, he just sits with a blank stare. “It’s like he’s not really there with us,” Rodriguez says.

Like every inmate in solitary who wrote to me, Hernandez refuses to talk much whenever mental health counselors come to his cell door, because others can hear—divulge too much and guards or other inmates can use it to harass you. Complaints are often ignored, and paranoia runs high. In late 2018, Hernandez argued for weeks with guards about being placed in a cell that he insists was spotted with black mold. One day, after leaving his cell for recreation, he refused to go back. He says guards called in backup wearing helmets and riot shields who forced him to strip, doused him in pepper spray, and then tossed him in a kind of solitary within solitary—cells where guards hold troublemakers for 90 days without their property. Later, he says, one of the guards came by and told him, “No hard feelings.” “How are you supposed to not have hard feelings?” he told me.

Hernandez says he now tries to limit his interactions to avoid confrontations—withdrawing even further into solitary.

IV.

“This is what happens to us who are locked in isolation too long, we become delusional.”

Michael Felder, held in solitary for eight years

Since the 1980s, solitary confinement has spread across Texas and the rest of the American prison archipelago, despite mounting evidence of the damage it causes. Research has found that people in isolation, even for short periods, develop crushing anxiety, delusional thinking, hallucinations, and the sudden onset of violent and often self-destructive outbursts. One study of brain activity in isolation showed signs of delirium and stupor after just a few days.

Experts who study solitary say one of the most striking aspects of its revival in American prisons is the excessive length of isolation. Terry Kupers, a psychologist who has spent most of his career studying what happens to people in solitary, including in Texas prisons, found that after several years in isolation, many people enter a state of what he calls “hyper-isolation” and stop responding to the minimal stimulation around them.

Kupers also describes a kind of “emotional numbing” that occurs after long periods in solitary, largely as a survival mechanism. At first, the isolation makes people angry and impulsive enough to, say, lash out at guards, which gets them into more trouble and extends their time in solitary. But after enough time, people start suppressing their emotions and retreat further into the hole. “They describe themselves as numb, the Walking Dead, zombies,” Kupers says.

Stories of prisoners smearing feces on the walls, mutilating themselves, and dying by suicide in solitary are common. In October, I traveled to the Coffield Unit in Tennessee Colony to visit Michael Felder, an inmate who was housed next to Russell Johnson, who killed himself in isolation last July. Felder, who has been in solitary for eight years, says Johnson was tormented by hallucinations in his final days.

“Solitary confinement became too much for him to deal with. He constantly talked about taking his life,” Felder told me. “We would talk about spirit-world demons trying to take him to their world. He would mention them entering his cell, trying to overpower him.” Johnson’s sister had begged officials to intervene, but prison staff never moved him.

Kupers says death penalty states that started throwing condemned inmates in solitary, a practice Texas adopted in 1998, saw a rise in the number of inmates forfeiting their appeals and asking for execution. In October 2016, Justen Hall—sentenced to death for the 2002 strangling of a woman in El Paso—wrote the judge on his case asking to abandon his appeals, including a motion for DNA testing on the murder weapon in the case. “I need to be put down like the rabid dog that I am,” Hall wrote.

“[T]hese walls 24/7 have broken me. It is taking every last ounce of will to even make it from day to day.”

Five months before his execution, Hall wouldn’t leave his cell to participate in a court hearing on a prosecutor’s motion to set an execution date.

On November 6, 2019, prison officials escorted me and other witnesses into a closet-like viewing room looking into Texas’ death chamber inside the Walls Unit. Hall, already strapped to a gurney by the time we entered, spoke into a microphone hovering about a foot above his mouth, apologizing to his victim’s family and then his own. His eyes closed and his breathing slowed after an unseen hand delivered a fatal dose of pentobarbital, Texas’ current execution drug of choice. Nineteen minutes later, by the time his face had changed from red to purple, he was declared dead.

V.

“I have been desensitized to a lot of feelings due to being denied human contact for almost 25 years. I don’t have much empathy for others and don’t share a lot of feelings. In a way, I’m less tolerant of others because I’m dependent on them for almost everything.”

Dennis Hope, held in solitary for 24 years

Jesse Madrigal dresses up whenever he visits his baby brother, David Madrigal. David was a sharp dresser before going to prison for life for killing a state trooper in 1991. “He always looked nice, so I do that for him now,” Jesse says. David doesn’t like having his photograph taken, so sometimes Jesse steps it up to coax one out of him. “I wear a suit with a tie and everything and I tell him, ‘OK, brother, I dressed for a picture.’ I want him to know that he’s special to me.”

In January 1997, David was sent to solitary confinement when, after a fight with another inmate at the Wynne Unit in Huntsville, he somehow wound up outside on the roof. Alana, David’s sister-in-law, who visits with Jesse every few months, says David insisted it wasn’t an escape attempt, but the incident was treated like one. “He kept saying, ‘I didn’t touch the fence,’” she says. David has been in solitary ever since.

For inmates with support on the outside, the harms of solitary confinement spread in two directions. Jennifer Ershabek, director of the Texas Inmate Families Association (TIFA) and the mother of a son who spent time in Texas prisons, told me she often hears from families in anguish over loved ones deteriorating in solitary. “As a mom, you hope that your children would grow up and flourish, but when they’re in solitary, all you see is them wither,” Ershabek says. “Their souls just shrink and wither away.”

Jesse says 22 years of isolation have made his brother a quiet, reserved man who won’t write or share much. What little David has divulged over the years has alarmed his family, which has tried—but failed—to find him a pathway out of solitary.

In recent years, TIFA and other prison reform groups in Texas have cited TDCJ’s use of long-term solitary as one of the reasons to create independent oversight for the prison system.

The oversight that did exist during the 1980s and ’90s was challenged in 1999, when Texas went back to federal court to end the monitoring of the state’s prison system that had begun under Ruiz. Judge Justice, who was still at the helm, excoriated the routine brutality and injustices of the system’s new and improved control model and argued for continued federal court monitoring. Although Texas prisons had changed, Justice wrote, that didn’t make them constitutional. He highlighted solitary in particular, describing “a world in which smeared feces, self-mutilation, and incessant babbling and shrieking are almost everyday occurrences.” Justice called the administrative segregation cells “virtual incubators of psychoses” and a cruel dumping ground for the prison system’s challenges.

Texas appealed Justice’s ruling, citing the newly enacted federal Prison Litigation Reform Act—lobbied for by Texas lawmakers with Ruiz in mind—which dramatically limited prisoners’ ability to bring lawsuits and courts’ authority to monitor prison conditions. In 2001, the federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals granted the state’s request, effectively stopping federal oversight and ending the Texas prison system’s nearly 30-year court battle with Justice.

During the 2019 session, the Texas House Corrections Committee took up a bill to create independent oversight for TDCJ. Meagan Harding, a lawyer with the Texas Civil Rights Project, testified about the pain of families with loved ones languishing in solitary for decades, saying they have nowhere to turn after hitting a wall with the agency’s grievance process. Representative Carl Sherman, D-DeSoto, was unconvinced that prisoners are kept in solitary for so long, interrogating Harding: “Do you have any data that would support that statement? I’d like to see the facts on that. Anytime a statement like that is made, I’d like to see the facts on that.” Lawmakers passed the proposal out of committee but never scheduled it for a debate or vote on the House floor. The Senate didn’t even consider it.

VI.

“Why would [TDCJ] want to show people something that is inhumane and morally indefensible; to lock humans in cages cut off from nearly all contact with other humans, for years and decades?”

Aaron Striz, held in solitary for 18 years

For the past several years, the Association of State Correctional Administrators has worked with the Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law at Yale University to study the scope of solitary in the United States and spotlight efforts to curtail the practice. In New Jersey, a long campaign by prison reformers led to a 2019 law that virtually eliminated long-term isolation. After a federal judge in Georgia gave a prisoner in indefinite solitary his day in court, the state agreed to limit solitary to two years. Under the settlement, Georgia is also required to provide tablets with “educational programs, email capability, music, and other media” to inmates in solitary.

In 2017, Colorado became the first state in the country to adopt United Nations standards of prisoner treatment, named after Nelson Mandela, which define solitary beyond 15 days as torture. Now isolated prisoners considered too dangerous to be around others are let out of their cells daily for at least four hours for classes and other activities at “restraint tables” with other inmates. The catalyst for Colorado’s shift came in 2013, after an inmate released directly to the street from solitary, where he’d spent seven years, appeared on the state prison director’s doorstep and shot him to death.

California’s recent history with solitary is perhaps most relevant to Texas. While both states built giant prison systems that came to rely on isolation, California has been forced to end some of the same policies that keep inmates in indefinite solitary in Texas prisons. California’s shift began in 2012 with a lawsuit and a hunger strike of 29,000 prisoners, who refused to eat for two months in protest of the widespread use of long-term solitary, leading to a settlement with the state that forced California officials to virtually eliminate what they call “secure housing.”

Keramet Reiter is a law professor at the University of California, Irvine who studied the state’s experiment with long-term solitary. When she first started researching the rise of supermax prisons, Reiter figured she’d find contentious public discussions about the cost of building thousands of new concrete boxes to confine inmates in near-total isolation, but instead found that almost nobody realized it had happened. “People literally didn’t know the first of these prisons had been built until prisoners started complaining about the conditions there,” Reiter says. “We’ve been running a mass experiment and we haven’t been keeping track of it.”

Reiter says recent efforts to reduce isolation appear to only scratch the surface. “I think most systems that say they’re not using segregation just relabel that population something else and house them in places where they’re doing functionally the same thing as solitary,” she said. Ending solitary, she says, will require as many solutions as the problems it was used to contain.

“Solitary has become a tool for anyone who doesn’t fit,” Reiter told me. “It’s a tool for dangerous people or people who are seriously mentally ill, a tool for people who are scared for their safety and need protection in the general prison population, or a tool for people who don’t fit anywhere else, like transgender prisoners.” She called solitary “the perfect magnifying lens” on the many problems of mass incarceration.

Landing in the Grimes County jail in 1997 for robbery so badly scared Aaron Striz, then 17, that he tried to escape before trial. “The redneck jail staff relentlessly taunted us about prison rape and what happens to young boys in adult prisons,” he later recounted to me in a letter. Striz and his co-defendants found a hole in the wall where an air conditioning unit had once been and broke out, only to be rearrested weeks later. When Striz tried to escape again, he ended up with assault charges that turned into a life sentence.

Striz, who says he was “young and scared but determined not to be a victim” when he got to prison, got into fights and sought protection from the Aryan Nations. In 2001, prison officials put him in solitary for gang affiliation, where he’s remained ever since. He says he’s asked to go through TDCJ’s gang renunciation program, but officials say he’s ineligible because of his previous escapes; he’s now suing over his continued placement in solitary.

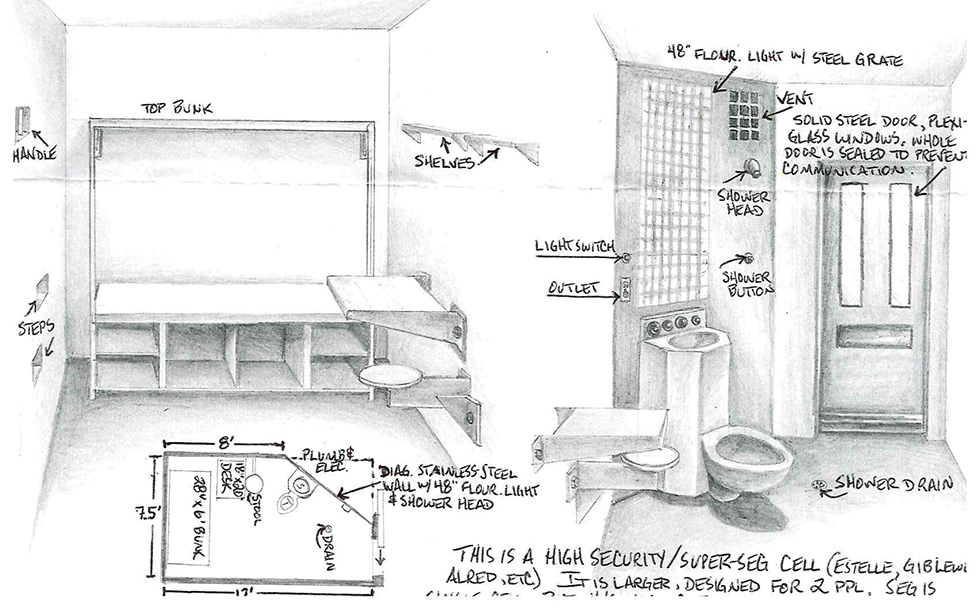

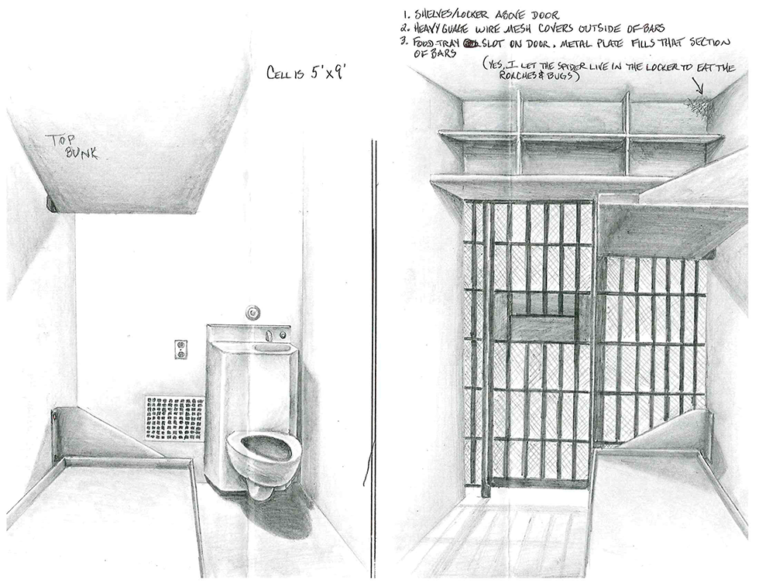

Despite months of requests, Texas prison officials wouldn’t let me see where inmates are housed in solitary. Striz, however, offered to send me detailed sketches of the three types of administrative segregation cells he’s lived in over the past 18 years. From August 2001 to October 2013, Striz was isolated at the Robertson Unit in Abilene in a small cell with a tiny slit window on the back wall. After that, solitary at the Estelle Unit was “the worst I’ve experienced,” he wrote. While the cells were slightly bigger and had showers, Striz claims guards used every excuse to avoid taking inmates out, saying, “There were stretches where I never left my cell for months.”

Since 2018, he’s been at the Darrington Unit south of Houston. He’s let out in the yard for recreation about twice a week. There’s a basketball hoop, but no ball. There’s also a pullup bar covered in bird droppings. The yard itself is enclosed with tall metal walls topped by a covering that blocks the sun, which Striz says he hasn’t seen in six years. “You can’t see anybody, you don’t see anything, there’s nothing,” he says. “You just walk around in circles.”

Top photo: Horses graze in front of the Polunsky Unit, outside of Livingston in East Texas. Photo by Alex Scott.