Somewhere It Hides a Well

Learning to look past borderland tropes in Presidio.

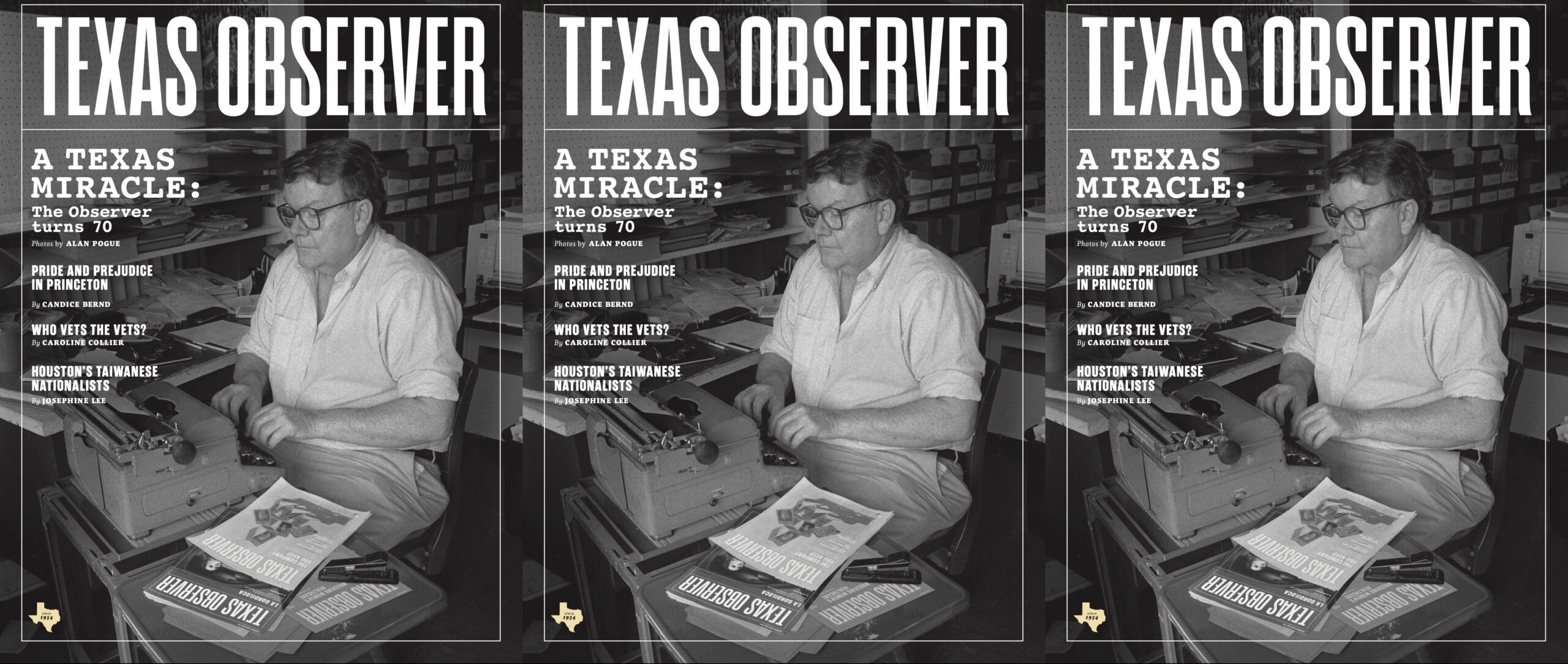

The photograph, taken in 1975, shows a long dirt road receding into blue mountains. A chain-link fence runs along the left side of the road, and on the right, a series of one-story adobe façades, pink like the dirt. Beside one of these structures is a man, his face obscured by the shade of his cowboy hat. His hands are in his pockets. A small, dark dog cocks its head in the direction of the man. This photo, the result of my Google search for “Presidio, Texas,” was my only visual point of reference before I moved there.

Three years ago, I left New York City for Presidio — a town nestled on the U.S.-Mexico border within a wild stretch of Chihuahuan desert — where I’d been offered a job to report for a community newspaper. After I moved, residents of the town would ask me how I was adjusting. Was it difficult coming all the way from the city? I didn’t know how to explain the sensation that I hadn’t arrived, but rather, returned.

The desert runs in my blood. My ancestors were bedouins of the Persian Plateau and my nomadic proclivities are evidence of that: I don’t believe much in fate, but I follow my feet.

“What makes the desert beautiful is that somewhere it hides a well.”

During my time in Presidio, I often found myself wandering toward the Rio Grande and contemplating its stagnant surface. Thanks to upstream agriculture and mining, the so-called Rio Grande has dwindled to a trickle in the Trans-Pecos region. Invasive plants such as salt cedar, which was introduced by the U.S. government in the early 19th century to prevent soil erosion, have narrowed the river’s path, slowed its flow and turned its waters silty and brackish. In fact, almost 50 percent of the water that flows within its channel from Presidio downstream is supplied by the Rio Conchos, whose headwaters reside in the Sierra Madre of Mexico. The confluence of the Rios Conchos and Grande — also known as la junta — is where Presidio and its Mexican sister city of Ojinaga meet.

This murky river over which one could throw a stone represents the international boundary line between the United States and Mexico. Each year, migrant bodies bloated and blue turn up along its shores, tangled in the salt cedar. Many who die here spent days traversing the much more treacherous desert surrounding it, carrying little more than a jug for water.

My mother emigrated to the United States from Iran when her country was in revolt and has hated the desert ever since, preferring to cool her eyes on aqueous landscapes and manicured lawns. When I moved to Iran after college, she couldn’t understand why I was so eager to return to the country she’d left years before, and why, when I moved to West Texas years later, I had returned once again to a land made of dust.

But there is magic there — though the desert does a good job of concealing it. “What makes the desert beautiful,” says the “little prince” of the popular children’s tale bearing the same title, “is that somewhere it hides a well.”

–

“Get a gun,” my friends and family in New York quipped before I moved to the border, “or a dog.” When I arrived at my new home, a pale-blue adobe casita at the intersection of a paved road and a dirt one, I soon realized how unnecessary these precautions would be. Presidio was safer than any place I’d lived. In small towns, where you eventually get to know just about everyone, it’s much harder to get away with bad behavior. For the first time in my life, I’d sleep with the front door unlocked. I kept the keys to my car in the cup holder.

I could say these things to friends back home, but it wouldn’t matter much. To them, I was in a far-flung place and no amount of detail seemed to mend that distance; it was strange terrain and anything I told them was merely a portrayal, as detached and out of context as the photograph of that man. Places outside the realm of familiarity are only as real as one imagines them to be. It’s easy to invent tropes to stand in for the real place.

As a journalist, I tried to use only the most unambiguous details in my dispatches, and as a result, sometimes left out the parts that felt inexplicable or obscure. But these were often the same details that were most human, fallible, lovely. How could I begin to characterize the hyphen between Mexican-American? And so all the stories I wrote began to fit into predictable narratives: failed immigration policy, Trump’s needless border wall, the so-called War on Drugs. I was always looking for stories that could represent the “bigger picture.”

I wrote about an undocumented woman and her 11-year-old granddaughter, Clarisa. I wrote about crossing the border illegally with them, a passage they made regularly, and of spending the night at their home in Mexico. I wrote about the monsoon that swept through and caused the Rio Grande to rise so high that on my return to Texas, I would have to cross the river on two steel cables dangling across its width. I wrote about this in the framework of border policy and how much it has changed since 9/11. The story fit the narrative.

After the storm, Clarisa took me by the hand and we walked down the road to watch an arroyo rush through the center of town. Her sandal had gotten stuck in the muddy undertow of the current and then bobbed up to the surface, suddenly swept away, and I ran along the arroyo’s edge to catch it. Later on our walk, Clarisa found a small, dead bird — a casualty of the short but violent storm — and dug its grave. She signaled the cross and said a prayer.

I did not write about how, before I left again, she asked me not to be like the other woman, an artist who’d come and taken her photograph but never returned to see her.

“Come visit me,” Clarisa said. “Of course I will,” I said, and meant it. I did not write about how I didn’t keep that promise.

How could I begin to characterize the hyphen between Mexican-American?

Nor did I write about Pilly, the ancient man who’d drive his teal truck 10 mph along the 50 mph road that ran in front of my home. The first time I got stuck behind him in my car, I gritted my teeth until he slowly pulled over along the shoulder of the road. As I pulled past him, I caught a glimpse: a tiny, wrinkled man with a bone-colored cowboy hat, straining to peer over his steering wheel, his gnarled hand raised in an effort to block out the setting sun. Beside him in the passenger seat was his wife, casually paging through a newspaper.

I did not write about the group of 12 children who stood uncertainly on the side of the road in the middle of town one afternoon, as a white-and-green Border Patrol van drove up to process and detain them. One girl, no older than 6, carried a toddler on her back and clenched the hand of another child as she climbed aboard, her fist shiny white but dirty like a bulb of garlic torn from the soil.

I did not write about my neighbor, Mr. Torres, hard of hearing and sight and sick with cancer, who would sit on his porch and sing to his dog variations of the song from Casablanca, “As Time Goes By.” “A dog is just a dog, a cat is just a cat,” Mr. Torres sang to its melody. At night, when I’d step outside to smoke a cigarette, I could hear the sounds of the old Westerns he’d watch at top volume on his television. Sometimes I just heard the mechanical sigh of his oxygen machine.

I did not write about getting stranded in Mexico yet again after a storm, the road home washed away by an arroyo, and how I waited indecisively, calculating whether I might be able to cross in my tiny car, or if I’d get swept away like Clarisa’s sandal. A man pulled up beside me in a truck and asked if I needed help getting across. He let another passenger in the car drive his truck, while he took the wheel of mine, navigating with ease across the rushing water.

I didn’t write about the traces of humanity that seemed to pervade these borderlands. I didn’t write about them, but now, as I lie awake at night with New York City’s noisy exhale rushing in my bedroom window, that’s all I can remember.