Stalled Program to Stem Farmer Suicides Gets a Second Chance in Congress

A USDA program to help farmers with mental health issues was authorized a decade ago but never funded. Now the U.S. Senate is proposing $2 million for the initiative.

Compared to the general population, farmers and ranchers are seven times more likely to take their own lives, a possible result of social isolation, financial stress and a dearth of mental health services in rural areas. So far, 2018 hasn’t done agricultural producers any favors. Prices for soybeans, corn and wheat have slumped. Median farm incomes for 2018 are expected to dip to negative -$1,316. A trade war brewing between the United States and China has prompted the Chinese to threaten tariffs on some of Texas’ most dominant agricultural commodities. And farmers’ mental health woes could be exacerbated by the state’s dismal rural health care infrastructure.

But there’s good news on the horizon. That’s because Congress is now considering actually funding the program it set up a decade ago to connect farmers contemplating suicide with mental health services. The U.S. Senate Appropriations Committee included in its USDA-FDA spending bill for 2019 up to $2 million for the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network, a program that could connect potentially suicidal farmers with mental health professionals, support groups, community outreach programs and other services.

“The Committee is deeply concerned by the high rate of suicides among agriculture workers, which is the highest overall suicide rate among all occupations according to the Department of Health and Human Services,” the bill’s text reads. The money would be disbursed by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture through competitive grants from state agriculture departments, universities and nonprofits.

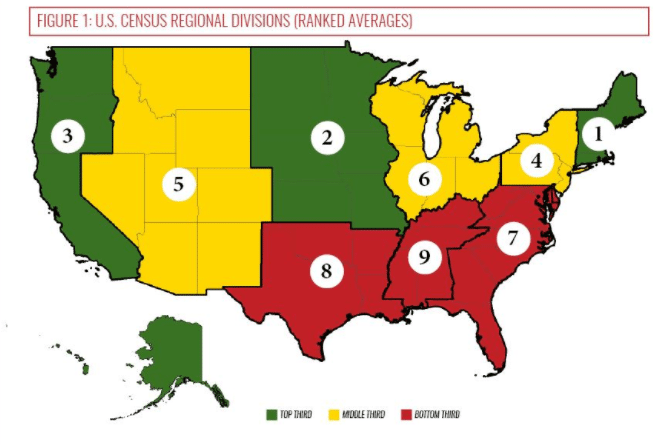

Texan farmers and ranchers operate almost exclusively in rural parts of the state, where access to health care is abysmal. In the state’s nearly 200 rural counties, there are only 1.8 psychiatrists per 100,000 residents, about half of the national rural average of 3.4 and a fraction of the 8.4 in large metros. Rural Texans on average have a much higher rate of suicide than folks in metro areas, and a 2016 analysis by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that people who work in the farming, forestry and fishing industries are seven times more likely to kill themselves than the general population.

The premise of the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network — to send money to states and nonprofits in an attempt to slow the rate of farmer suicides — isn’t a new one. The program was first pitched as part of the 2008 Farm Bill, an occasional omnibus proposal encompassing the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, land conservation initiatives and other initiatives, but Congress never funded the program. (The network wasn’t even included in the 2014 Farm Bill.) Legislators from both chambers are currently working up their 2018 versions of the bill, and this time around, it looks like the the stress assistance network could actually get funded.

If it does, it’ll mark the completion of a decade-long push to secure help for farmers grappling with depression and other mental health problems, said Minnesota Representative Tom Emmer, a Republican who this year introduced legislation to reauthorize the network. For farmers, suicidal ideation can be triggered by financial woes, natural disasters, isolation and a myriad of other factors, but “this is not something that’s widely known within the general population,” he said.

“There’s no reason why [funds] shouldn’t have been appropriated back in 2008. This should not have been an issue,” said Emmer, who added that Texas Representative Mike Conaway, a Republican from Midland and the Farm Bill’s chief author, has been “more than supportive.” Conaway’s office forwards questions regarding the Farm Bill to House Committee on Agriculture, which on Tuesday did not return a request for comment.

Funding the program is not yet a done deal. The proposal must still pass the full Senate and survive negotiations with members of the House, some of whom have brought the larger Farm Bill discussions to a standstill in recent weeks. But the proposal is at the very least a good omen, said Andrew Jerome, communications director at the National Farmers Union, which pushed last month to get the network funded.

“This funding is a step in the right direction,” Jerome said.

Need help? In the United States, call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.