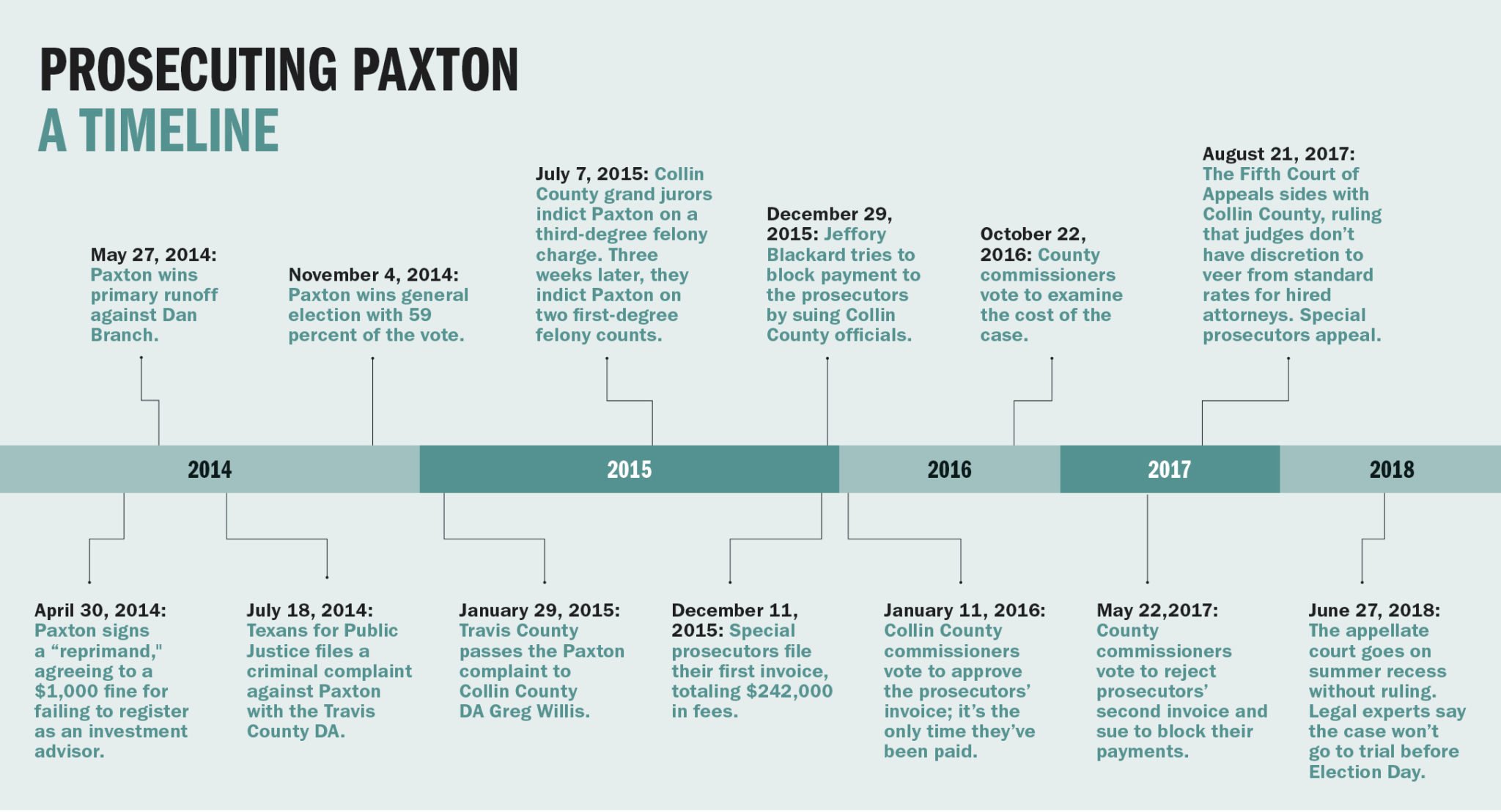

Three years ago, just months after being sworn in as Texas attorney general, Ken Paxton’s days seemed numbered. In July 2015, a grand jury had indicted Paxton on three felony charges — two for securities fraud and another for failing to register with the state as an investment advisor. Unlike when Rick Perry faced felony indictments the previous summer, top Republicans were either silent about Paxton’s criminal troubles or gave desultory statements on the importance of due process. One poll conducted in the weeks after Paxton’s indictment found that a majority of GOP voters wanted him to resign.

Even before the criminal charges, Paxton had taken his lumps. In 2014, the bruising GOP primary for attorney general fueled scrutiny into his sketchy business dealings and had even led to a civil fine for violating state securities law. Paxton’s main opponent, Dan Branch, urged GOP voters not to “promote a lawbreaker as our standard bearer to replace Greg Abbott.” Yet this year, Paxton didn’t draw a single GOP opponent. His case is now dragging into its fourth year. If a trial ever happens — and that’s in doubt — it will come long after voters decide whether to re-elect him in November. In fact, so few people seem to remember Paxton’s legal problems that his underfunded Democratic challenger, Austin attorney Justin Nelson, has spent most of his campaign reminding anyone who will listen that the state’s top lawman faces felony charges that could put him in prison for the rest of his life.

“The people who know the charges are still pending, they’re the smallest group,” Nelson said. “They don’t understand why he hasn’t gone to trial in three years. They’re like, ‘Why else would he not be going to trial?’”

The answer to that question lies in Collin County, Paxton’s home turf and one of the richest, reddest counties in Texas. After a nomadic childhood as an Air Force brat, Paxton settled in McKinney, the county seat, once he got his law degree. He worked for J.C. Penney and a corporate law firm before starting his own practice in 2002, the year he was elected to the Texas House. Like ward politics in Chicago or the politiquera system in the Rio Grande Valley, conservatives in the Dallas ’burbs have built their own powerful political machine in the land of turfgrass, megachurches and the Cheesecake Factory. Paxton’s influence in the area is so great that last year prosecutors convinced a judge to move the case to Houston, arguing the state couldn’t get a fair trial in Collin County. In legal filings, prosecutors even have a shorthand for the Paxton machine.

“Paxton’s posse of spokesmen, supporters, and surrogates — a clique herein collectively referred to as ‘Team Paxton’ — has embarked on a crusade clearly calculated to taint the Collin County jury pool,” prosecutors wrote. “Paxton is not the prototypical Collin County criminal defendant being made to stand trial for a trio of felonies: he is one of Collin County’s favorite sons.”

Since the indictments came down, Team Paxton has built a firewall around its proudest political investment, twisting the felonies into a tale of Paxton’s persecution by “liberal Republicans” and Democrats.

But Team Paxton’s biggest coup, according to prosecutors, has been defunding and derailing the case for years. First, one of Paxton’s deep-pocketed supporters sued to stall the case; then his allies in Collin County government took up the fight amid pressure from North Texas tea partiers who chastised them for funding a “witch hunt.” At the same time, Paxton’s friends, his pastor, and even Republican state Representative Ron Simmons have sued his alleged fraud victims with the assistance of one of Paxton’s criminal defense attorneys.

Cal Jillson, a political scientist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, summed up the saga as “political dark arts.”

“The Republican Party apparatus and Paxton supporters in Collin County have worked assiduously to help him delay this beyond Election Day,” he said.

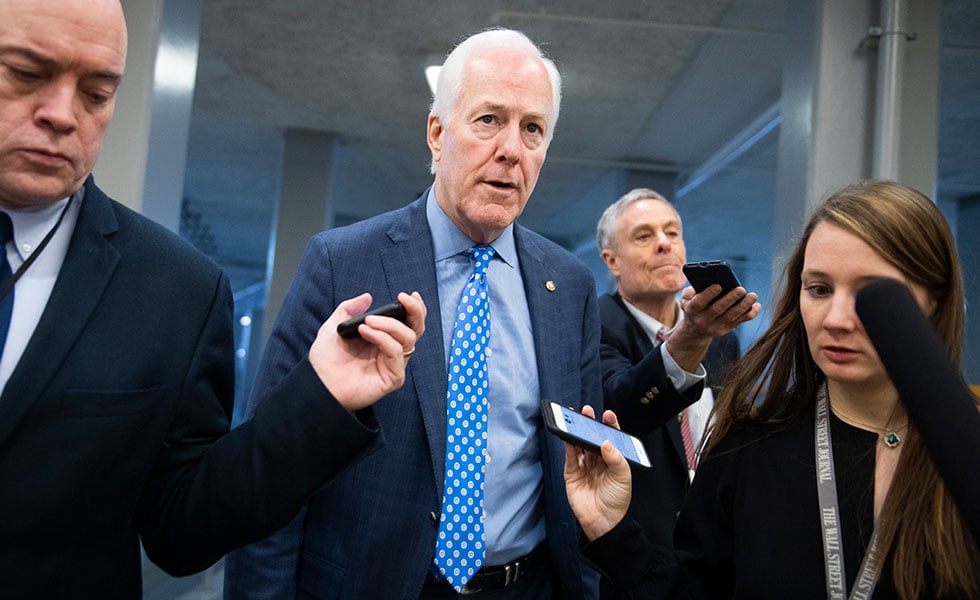

Neither Paxton’s campaign nor his defense team responded to numerous requests for an interview, nor did they respond to questions the Observer sent by email. But that’s not surprising: Paxton rarely gives interviews to the media, other than Fox News, and his political team has a barely concealed vendetta against the Dallas Morning News, once accusing one of the paper’s reporters of “stalking.”

With his prosecution stalled, Texas’ scandal-prone attorney general has managed to rehabilitate his image among the Republican base, the only slice of the electorate that has mattered in a statewide race here for the past quarter century. He’s gone from a grinning mugshot to regularly mugging on Fox, decrying everything from LGBT rights and gun control to protections for Dreamers and patients with pre-existing conditions. He’s hewed even closer to the religious right, turning his pastor into the voice of the attorney general’s office and appointing to a top post someone who called transgender kids part of “Satan’s plan.” The political witch hunt narrative has only made him a more beloved martyr among the faithful. His prosecution is now his persecution.

Somewhere along the way, Team Paxton turned the criminal case against Texas’ top lawyer into a peculiar crusade for criminal justice reform. The trouble with the system, they say, is that the rich, the powerful and the well-connected just can’t get a fair shake.

When Paxton was first elected to the Texas House in 2002, he was something of a moderate, advocating for more public education spending and light-rail in the suburbs. The Dallas Morning News heralded him in 2004 as a “consensus builder.” But years later, Paxton emerged as one of the most adept surfers of the tea party wave that transformed the Texas GOP. After a failed attempt at dethroning the more moderate Joe Straus as speaker of the House in 2010, Paxton ran for an open seat in the Texas Senate, clearing the GOP field with the help of Empower Texans, an arch-conservative group that frequently plays kingmaker on the right. After serving only two years in the Senate, Paxton leaped at his chance to run for attorney general. But so did two other prominent Republicans, Texas Railroad Commission Chairman Barry Smitherman and Dallas state Representative Dan Branch.

Paxton’s establishment GOP opponents portrayed him as a slimy politician who’d used public office to pad his business portfolio. In February 2014, Smitherman even bought airtime to spotlight legal clients who accused Paxton of profiting behind their backs. One ad featured a 2009 lawsuit by a Dallas couple who claimed Paxton hadn’t disclosed kickbacks he received for steering them into a doomed real estate scheme with an investor buddy and political donor named Frederick “Fritz” Mowery.

Paxton’s legal problems intensified in April 2014, when the Texas Tribune reported he hadn’t been registered with the state when finding investors for Mowery, a violation of a state law designed to protect against fraud. A subsequent investigation by the Texas State Securities Board concluded that Paxton had solicited investors without registering during three separate years, most recently in 2012. In the heat of the primary, Paxton signed a “reprimand” with the securities board, agreeing to pay a $1,000 fine and waiving his right to appeal the punishment. That would prove to be a pivotal decision.

Paxton called the lapse an honest mistake, even though he himself had voted for the 2003 bill that made such conduct a felony. Still, all he had to do to win was keep his head down and hide from the press. Paxton beat his Democratic opponent — none other than Sam Houston, a Houston attorney — by more than 1 million votes. It is Texas, after all.

In July 2014, Texans for Public Justice, the same left-leaning group that spearheaded the criminal charges against Rick Perry and Tom DeLay, filed a criminal complaint against Paxton in Travis County, arguing he had effectively admitted to a third-degree felony. Travis County eventually said it lacked jurisdiction and bounced the complaint to Dallas County, which said the same thing.

“Paxton is not the prototypical Collin County criminal defendant being made to stand trial for a trio of felonies: he is one of Collin County’s favorite sons.”

Travis County also passed the complaint to Collin County, which put Paxton’s fate solely in the hands of a close friend, District Attorney Greg Willis. The two had met in their college days at Baylor in the 1980s and were off-and-on business partners. For instance, Willis and Paxton helped put together a deal to buy undeveloped land in McKinney, change its zoning and then flip it to the county at a big profit (a grand jury later investigated the deal but took no action).

To squash the complaint against Paxton, all Willis had to do was sit on it for a few months until the three-year statute of limitations was met. That’s where things were seemingly headed until a shit-stirring lawyer named Ty Clevenger got involved.

A former cop and journalist who’d moved from East Texas to Collin County around the start of Paxton’s legal drama, Clevenger considers himself part of the “Rand Paul strain of the GOP.” He has made it a personal crusade to go after ethically challenged legal figures, including skeezy judges, Hillary Clinton’s lawyers and, in 2014, Paxton.

Fearing that Willis would run out the clock, Clevenger did something unorthodox: He personally tracked down all 12 members of the Collin County grand jury and urged them to investigate Paxton. On March 6, 2015, he mailed letters to their homes and workplaces and even hand-delivered a few to a Plano church several jurors attended.

“A lot of grand jurors, the solid majority, don’t want to leave the reservation,” Clevenger told the Observer. “But there’s usually one or two on there that, if you give them solid facts that something is amiss, they’ll start asking questions.”

The gambit worked. Days later, Clevenger says a grand juror called him for more information. In April, the grand jury asked Travis County to send everything it had on Paxton; this appeared to prod Willis into asking the Texas Rangers to “follow up” on the complaint before he recused himself entirely later that month.

A local judge, Scott Becker, also tapped two high-profile, media-savvy Houston lawyers to serve as special prosecutors if the Rangers’ investigation led to criminal charges. (A judge would later add a third Houston lawyer to the case.)

In early August, Collin County officials unsealed a third-degree felony charge against Paxton for his failure to register as an investment advisor. The grand jury also approved two more serious counts of securities fraud, first-degree felonies that accuse Paxton of persuading two investors — one of them Corsicana state Representative Byron Cook — to invest in a troubled North Texas tech firm without disclosing he’d been compensated for it.

Paxton pulled together a top-dollar defense team, which he funded by raising money from political donors, friends and out-of-state benefactors — an ethically dubious decision that invited an inquiry from the Texas Ethics Commission. One “gift,” a $100,000 donation from a CEO whose company was being investigated by government agencies, including the Texas attorney general’s office itself, triggered a separate bribery investigation, which went nowhere.

Before the indictments, Team Paxton attacked everyone who pushed for the grand jury investigation, from Texans for Public Justice to Clevenger, crying “Witch Hunt!” long before Donald Trump learned the trick. After the indictments, they attacked a judge.

Conservatives in the Dallas ’burbs have built their own powerful political machine in the land of turfgrass, megachurches and the Cheesecake Factory.

Paxton’s motions to dismiss his charges focused in large part on Chris Oldner, the Collin County judge who oversaw Paxton’s grand jury. When they first came down, the charges were supposed to be sealed until Paxton surrendered at the jail days later, yet Oldner’s wife almost immediately began texting a county commissioner with the scuttlebutt. Team Paxton heard through the grapevine that Oldner’s wife was blabbing, and later that day the attorney general, his wife, Angela, and one of Paxton’s senior advisors called the commissioner, asking her to turn over the texts and write an affidavit about what happened.

From there, the defense spun what prosecutors called a “Grassy Knoll-like conspiracy” accusing Oldner, a Republican whom Rick Perry first appointed to the bench, of sabotaging the grand jury process in order to embarrass Paxton and ensure he was indicted. In legal filings, the special prosecutors hired to handle the case — Houston attorneys Brian Wice, Kent Schaffer and Nicole DeBorde — compared the defense strategy to the dodgy frat-boy antics of Animal House, citing in a footnote the scene where John Belushi and company conspire to cover up a car they just trashed (“It’s gotta work better than the truth”).

At the end of 2015, Oldner told a North Texas TV station that Team Paxton attacked him because they’d “reached a desperate place in their defense.” The dustup also underscored why no local judge would touch the case — either favoritism or local infighting could taint it. Oldner, who recused himself as soon as the charges were filed, said he and Collin County’s other judges had already agreed that an out-of-town judge should preside over any resulting criminal case.

As far as Paxton’s motions to dismiss the charges, the Tarrant County judge brought in to handle the case ultimately ruled them to be “without merit.”

So then Team Paxton went after the special prosecutors.

In recent decades, as Dallas began to trend blue, the suburban sprawl boomtowns of Collin County — first Plano, then Frisco and McKinney — became the new conservative heartbeat of Texas.

With a median household income of $86,000, the county is home to some of the wealthiest communities in Texas. One school district, McKinney ISD, shelled out nearly $70 million for a new football stadium. In 2014, Money named McKinney the best place to live in the country. The next summer, video surfaced of a McKinney cop barrel-rolling through a pool party of mostly black kids, pulling a gun on some unarmed “noncompliant” teenagers and slamming one bikini-clad girl facedown into the grass.

Churches are an epicenter of political power in Collin County, and Prestonwood Baptist, where the Paxtons worship, is among the most important. At Prestonwood’s sprawling main campus in Plano, the church welcomes visitors in a palatial foyer with stained-glass panels for all 66 books of the Protestant Bible; inside, the place takes on the feel of a convention center, with a cafe, bookstore and giant stairwells that lead to the main sanctuary. The services have a professional sheen; a high-decibel sound system carries the stage show, where a band with nearly as many members as the Polyphonic Spree churns through a half-hour praise-and-worship set of pop-adjacent contemporary Christian hits.

Not long after Paxton became attorney general, he named Prestonwood pastor Marc Rylander as his communications director. At Prestonwood, Rylander had grown accustomed to battling the press, chastising newspapers for publishing same-sex wedding announcements. As Paxton’s mouthpiece, he’s preached a remarkably combative view of the media, going so far as to encourage government workers to stall reporters’ information requests. “What you see in the news is opinions of what people wrote on Twitter and social media during the day,” he told an open government seminar earlier this year. “It’s gotten so bad in newspapers, especially, that I almost have gotten to a point where I avoid the newspaper people at all cost.”

Prestonwood is a surprising nexus for Paxton’s intertwining legal and political battles. Last year, Mike Buster, the church’s executive pastor, was among several Paxton affiliates who sued Representative Byron Cook and another alleged victim in the criminal case. Buster claims Cook fleeced him out of “a substantial percentage of his net worth” by recommending mineral rights deals without disclosing that he’d benefit from the sales — an echo of the charges against Paxton. Representing Buster is one of Paxton’s criminal defense lawyers, who’s also representing state Representative Ron Simmons in a lawsuit he filed against Cook this summer making similar claims. Simmons, a Paxton ally and Prestonwood member, last year filed two anti-trans “bathroom bills” that roiled the Texas Legislature — legislation that Cook helped block, only further tainting Paxton’s legal mess with party infighting.

Cook, through his attorney, wouldn’t comment on the lawsuits. But in a court filing, he and the other defendants accuse Paxton of using his friends “to assist in a political mudslinging campaign” to tarnish the reputations of key witnesses in the criminal case.

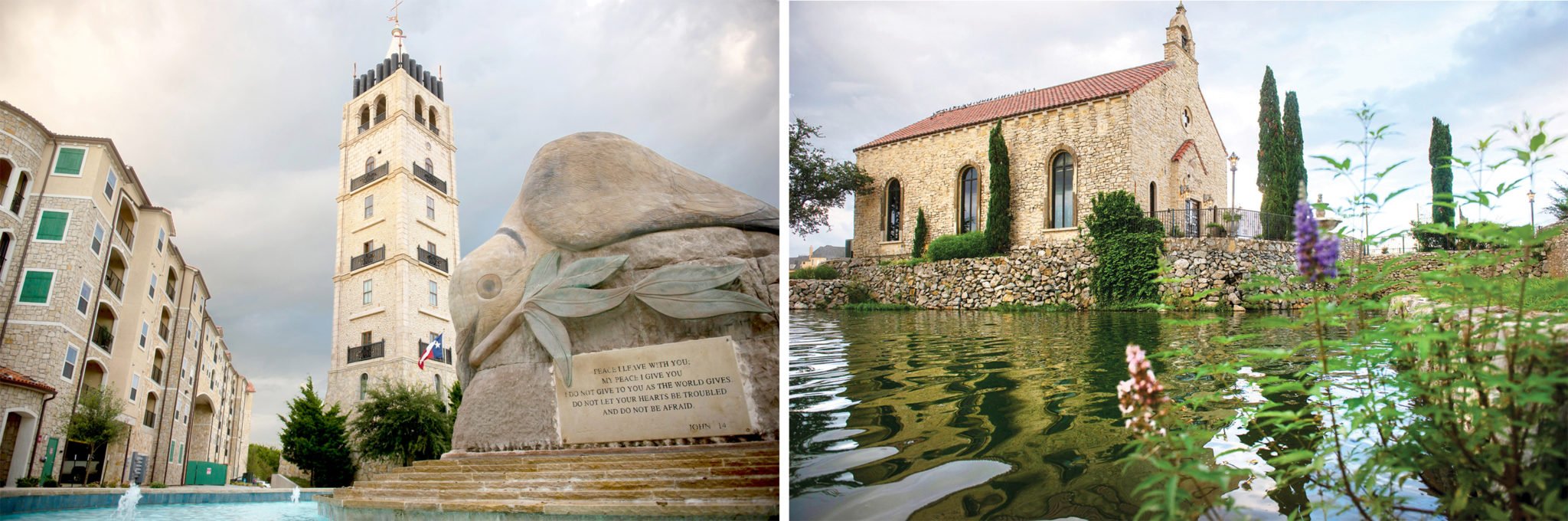

But perhaps no one has been more pivotal in Paxton’s fight than Jeffory Blackard, a North Texas real estate developer with a heart for Jesus and a penchant for master-planned communities. His chef d’oeuvre is Adriatica, an ersatz Mediterranean villa he built next to a Panda Express in McKinney.

Blackard pioneered the legal strategy that ultimately derailed Paxton’s trial for years. By convincing the courts to cut off the prosecutors’ pay, Team Paxton effectively brought the criminal case to an indefinite halt. In two lawsuits against the all-Republican Collin County Commissioners Court, Blackard challenged the $300-an-hour rate prosecutors negotiated with the Republican Collin County judge who hired them. He argued that, per the county’s standard rules for appointed attorneys, any pretrial work by the special prosecutors should be capped at $1,000 each, total — about $2 per hour so far. Ironically, Blackard’s lawsuits forced the county to hire an attorney to defend itself — at $375 an hour.

Blackard deferred all questions to Edward Greim, a Missouri lawyer who led Blackard’s legal fight against the Paxton prosecutors. An affiliate of the Thomas More Society, a conservative Catholic legal group, Greim has been involved in a laundry list of conservative legal spats across the country, including defending former Missouri Governor Eric Greitens, who stepped down this year amid blackmail charges and threat of impeachment. Another irony: Greim and another attorney sought more than $150,000 in taxpayer money to represent the governor.

Greim wouldn’t talk much about the criminal allegations against Paxton, saying he simply had “questions” about how they arose. But he said the prosecution is fundamentally unfair because the legal system is treating Paxton differently than an “ordinary criminal defendant” — a 2018 twist on the late 19th century Anatole France quip that “the law forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, beg in the streets and steal loaves of bread.”

In an email to Collin County officials last year, he said prosecutors shouldn’t be paid more to go after public officials because that would “create special exceptions based on the person involved.”

“What happened to Paxton could happen to anyone,” Greim told the Observer. “You don’t have to be running for attorney general to have provoked the ire of local power players.”

Throughout 2016 and 2017, Blackard, Empower Texans and other conservative activists flooded county meetings demanding that the commissioners defund the prosecution. One woman defended Paxton as a “major force against President Obama’s illegal immigration, his amnesty, his dangerous transgender bathroom ordinance.” To spread the message, Blackard even connected his pal Rick Santorum with a local TV reporter, who aired a piece with the Bible-thumping former Pennsylvania senator saying Paxton’s prosecution was “raping” Collin County taxpayers.

The pressure was relentless. Text messages first obtained by the Dallas Morning News’ Lauren McGaughy show a gaggle of North Texas lawmakers brainstorming how to force county leaders to kill the fees. The goal, per Plano Republican state Representative Jeff Leach, another Prestonwood Baptist member: “To stop the millions of our taxpayer $$$ — including $ from our OWN pockets — to support this travesty that is happening to General Paxton.”

The commissioners proved to be a soft target. Most had campaigned for or donated money to Paxton over the years. At one meeting, Collin County Judge Keith Self asked the special prosecutors to resign and questioned the need for “gold-plated justice” in Paxton’s case. In May 2017, the commissioners voted to take up the fight themselves and sued to block prosecutors’ fees.

Chris Hill, a commissioner who, after winning his March primary, will likely soon become county judge, argues that politicians and other high-profile defendants should be prosecuted just like any regular person. That means any lawyers appointed to the case should be paid just like any other case, with no exceptions for “unusual circumstances” like, say, the prosecution of the state’s top lawman. “Our decision wasn’t political at all,” he told the Observer. “We treated this case impartially as we would any other case.”

The payment matter now sits before the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the state’s highest criminal court. The prosecutors on the case — Wice, Schaffer and DeBorde — haven’t been paid in more than two years and have indicated they’ll quit if appeals don’t shake out in their favor. Defense lawyers across the state have warned that a high court ruling agreeing with Team Paxton could have devastating effects on indigent defense, effectively preventing judges from hiring lawyers who are qualified to handle complex cases.

Several district attorneys have also said such a ruling would make it difficult, if not impossible, to prosecute well-heeled, high-profile politicians, especially when the charges land at home. As Paxton’s prosecutors told the court, “Most criminal defendants don’t have millionaire pals, supporters and donors with the time and money to defund their prosecutions.”

Paxton’s benefactors at Empower Texans have pushed the “political prosecution” narrative around his case from the beginning, which makes sense. He has, after all, proven to be a worthwhile investment.

The two have built a symbiotic relationship — since his election, Paxton’s office has helped the group stymie get-out-the-vote efforts in public schools. He also refused to defend the Texas Ethics Commission against a lawsuit by the group seeking to dismantle campaign finance laws.

Nelson, Paxton’s challenger, says he fears the saga that developed around Paxton’s criminal case is the new norm — that even when the prosecution of a public official is rooted in an admitted violation of state law, supporters will attempt to blur everything by crying “Witch Hunt!” “There are the obvious comparisons to national politics,” he said.

Yet, even as Empower Texans puts Paxton’s case in the same vein as the 2014 Rick Perry indictment, some Republicans familiar with it privately admit there are marked differences. Perry, for instance, was prosecuted for using his veto power to pressure a political rival, while Paxton’s problems stem from the admitted violation of a law he helped create. All of which is to say even some conservatives I spoke to quietly fear Paxton could be a ticking time bomb if — more likely when — he’s re-elected.

“Most criminal defendants don’t have millionaire pals, supporters and donors with the time and money to defund their prosecutions.”

The Paxton name hasn’t lost its sheen in Collin County. Angela Paxton, who won the primary for her husband’s old state Senate seat by a landslide against a well-known and better-funded opponent, made a show of scolding any Republicans who might dare mention her husband’s charges. The charges were a third rail all primary season, something conservatives wouldn’t discuss out loud — except to reiterate how unfair the case is. At one point, Angela’s opponent even put out a statement decrying Paxton’s prosecution.

One apparent casualty of the infighting is Scott Becker, the district court judge who appointed the special prosecutors to Paxton’s case, negotiated their pay deal and has been demonized by conservative groups like Empower Texans ever since. A Republican first appointed to the bench by Perry in 2010, Becker ran unopposed in the 2014 primary and general election.

This year, he couldn’t even make a runoff, as Jennifer Edgeworth, a local attorney backed by Empower Texans, won more than 50 percent of the vote. An Empower Texans leader later crowed in a blog post: “Voters toss judge who launched Paxton prosecution.”

Becker’s losing campaign slogan: “Justice not politics.”