Working for Superman: Texas Schools Turn to Hero Superintendents

School districts often bring in hotshot superintendents to save the day. But is star power what schools really need?

A version of this story ran in the November 2013 issue.

On a muggy August morning in 2012, school buses full of teachers, janitors, cooks and other workers converged on the Ellis Davis Field House, a blocky modern building named for a beloved basketball coach and teacher who spent more than two decades at Dallas’ Roosevelt High School. They’d been summoned to meet a man who promised to change everything, to make the Dallas Independent School District (DISD) the best in the country.

The buses arrived precisely on time from schools around the city. Some of them weren’t air-conditioned, and one teacher, carsick and overheated, vomited along the way. It was the last prep day before the new school year began, and many of the teachers weren’t happy to be yanked from their classrooms. From the buses, they funneled onto a pedestrian bridge to the arena, pouring down the chute like cattle to the auction, in pre-sorted herds of red, blue and black school T-shirts. Inside, a classical ensemble of student musicians provided a soothing soundtrack to a slideshow of “Fun Facts” about the man of the hour, Mike Miles: “He once spent weeks in the hospital after surviving a plane crash”; “His poetry won him a prestigious Mellon Fellowship in the Humanities.”

Miles had designed the show as his grand debut in front of his new school district, and he’d summoned his new employees to bear witness. Miles had already been on the job more than a month, and new data released in summer 2012 showed Dallas’ school district wasn’t exactly in need of saving. On his first day as superintendent in July, Miles announced encouraging news: Since 2007, the graduation rate had risen 15 points, up to 77 percent. Dallas ISD’s test scores had improved over the previous eight years, outpacing the average improvement around the state. But many of its schools were still struggling mightily, and plans to reform the curriculum had stalled under sharp budget cuts. Miles arrived with a bold promise: He’d transform Dallas into the country’s No. 1 urban school district in just eight years, with 90 percent of its students graduating on time, and 60 percent reaching college-ready scores on their SATs and ACTs.

But a month into his new job, Miles already had critics wondering if he could deliver on his promises. He’d come from a Colorado school district of 11,000 students to run a district of 160,000 students with nearly 20,000 employees. Dallas is notoriously harsh on its school leaders, and much of the city seemed to have the knives out for Miles for hiring choices he’d already made, for the plans he had in store and for his attitude. Business leaders who’d lobbied for Miles’ hiring even teamed up to buy space on two freeway billboards reassuring Miles that he was, indeed, welcome in Dallas. As the new school year began, Miles seemingly tried to allay his critics’ fears with showmanship.

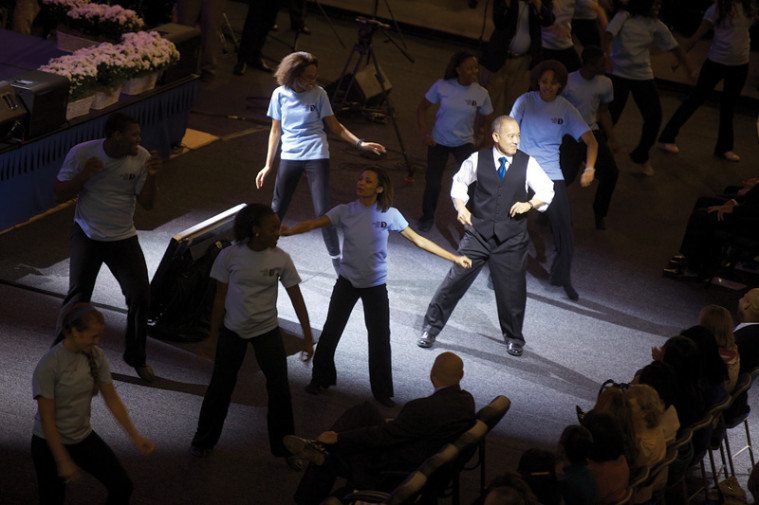

Inside the arena, most of the teachers and school workers heard Miles arrive before they saw him, heralded by an infectious cheer spreading from the front seats back to the arena’s upper rows. The school workers craned their necks for a glimpse of Miles in a vest, his suit coat cast aside, dancing in line with students to Yolanda Adams’ “I Believe.”

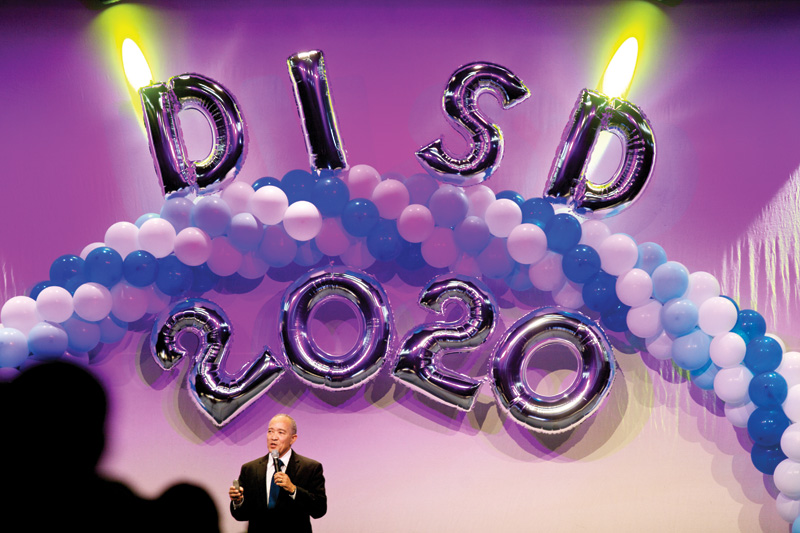

Miles continued his performance onstage with a PowerPoint clicker in his hand and a little microphone tucked around his ear. Miles laid out his ambitious plans for the schools: cutting the dropout rate and closing the racial achievement gap on tests. Balloons behind him spelled “DISD 2020,” a nod to his “Destination 2020” reform plan. (In Colorado, he had crafted a reform plan called “Destination 2016,” which featured the Starship Enterprise on its cover.)

According to “Destination 2020,” it’s important for the district’s staff to share a common direction, and in the spotlight onstage Miles told them just where they were headed: “course 267, mark 5,” he said—coordinates he said he’d made up. What mattered, he said, was that they reached their destination together. He didn’t have to say what would happen to anyone with a classroom on a different course. Within a year, hundreds of teachers and a quarter of the principals in the field house that day would either be fired or resign from DISD’s new course.

But from the stage that day, Miles sold his new direction like a motivational speaker. He played movie clips from Gladiator, Hoosiers and Stand and Deliver, calling on teachers who possess “the hero characteristic” to stand up and make themselves known, like he was the guy handing out red capes. It was a production to inspire the sort of young and idealistic teachers for whom systemic change seems a solid personal goal for the school year. Those less receptive to heady oratory from a new boss, those who’d been around to see bright-eyed new superintendents arrive to fanfare and apologetically leave, found the event a waste of time, just like they expected. And non-teachers among the crowd got to ride back to school considering just what “the hero characteristic” looks like in a custodian.

This is how Dallas got in on the latest craze in urban school reform, with a one-man Aspen Ideas Festival in a basketball gym. Mike Miles—dancer, stage-prowler, motivational movie-clip dispensary—was something the city had never quite seen before. The hero school chief had arrived.

Besides football coaches, school superintendents are government’s best-paid, most coveted and most controversial employees. In big-city school districts, they manage millions of public dollars, run campaigns for school bonds and tax increases, and employ tens of thousands of people. But it wasn’t always so. At one time, there were no superintendents. For a while, even in the biggest cities, the schools ran themselves. Dallas, for instance, was without a superintendent until 1884, when local school trustees installed W.A. Boles, “teacher of shorthand (pencil system), and lecturer,” as the city’s first superintendent. He lasted one year.

Some rural districts aren’t so far removed from the old days of school leadership. There are about 15,000 superintendents across the country, and 17,500 school districts. Lots of districts share their leaders. But even a country superintendent is a community leader, often running the largest employer in town. Along with the mayor and the minister, the superintendent is a voice of authority and consolation in times of crisis. Of the three, the superintendent is usually the best paid.

For a long time, school superintendents managed only money and resources. The curriculum “standards movement” of the 1990s—meant to bring consistency to what students learned from school to school—forced superintendents to answer for academics. The push for more testing followed, to guarantee that schools were teaching those academic standards well, and the responsibility for those test results fell on the superintendents as well. It became the superintendent’s job to ensure that each new layer of academic requirements—backed by state and federal laws like the No Child Left Behind Act—made it into the classroom. And the superintendent had to make sure the results looked good to people outside the schools.

Michelle Young, who directs the University Council for Educational Administration at the University of Virginia, says the No Child Left Behind Act upended the relationship between schools and their central offices when it brought test-based accountability to schools across the U.S. Today, she says, “the district is on top, mandating instead of supporting.”

No Child Left Behind brought new attention to improving schools that were struggling, but it also created a sense of urgency and pressure for school districts to take drastic measures to improve, at least according to a few narrow measures like math and reading test scores, and graduation rates.

Curtis Brewer, an education researcher at the University of Texas at San Antonio, says the primacy of test scores has evolved during the past four decades. In the 1960s, policymakers tied improving education to fighting poverty. President Lyndon Johnson conceived of school improvement in poor and minority communities as just one piece of his “War on Poverty.” The 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act coincided with the creation of Medicaid and Medicare and food stamps. But as the grand sense of post-war possibility gave way to a narrower focus on rational, modest goals in the 1970s, policymakers separated educational improvement from civil rights. Jimmy Carter’s creation of the Department of Education set the stage for judging schools on test scores without admitting or addressing the social challenges they faced.

Today, kids come to class carrying all the stresses of poverty, family dysfunction, youth, and cultural assimilation, and their school leaders are judged by how well they perform on a standardized test. While some superintendents come into districts promising they’ll work miracles to turn schools around, Brewer says the job is really more like middle management. “Somebody else defines their goals, somebody else defines what good looks like,” he says, and they don’t get to choose their students. “We look for this hero because we look for a solution to a problem that is not solvable in a narrow approach.”

The best known of these superintendent heroes are Michelle Rhee, the Washington, D.C., schools chancellor from 2007 to 2010, and Joel Klein, the federal prosecutor who tackled Microsoft before becoming New York City’s school chief from 2002 to 2010. Both came in with mandates to break up old systems and cut waste, both angered teachers and communities by closing schools and ousting principals. They weren’t the first hero school chiefs, but they were the first to become national media stars.

In December 2008, Time featured Rhee on its cover, stern-faced and holding a broom—a custodian, at last, with the hero characteristic—beneath the headline “How To Fix America’s Schools.” The suggestion was that Rhee knew the answer when, of course, she didn’t. She had an answer that she was taking for a whirl in a big-city school district. Like the urban-crime epidemic a decade earlier—when police chiefs rode into big urban jobs with mottos like “community policing” and the “broken windows theory”—the drive to “fix” America’s schools made stars of education-interested big-shots who talked a good game.

Cities found their new school chiefs in unconventional places. Military brass, lawyers, leaders from foundations or higher education—big urban districts tried them all.

And when you hire someone promising miracles, you pay them the miracle-worker rate. Klein earned $250,000 a year as New York Schools chancellor—just a fraction of the $2 million he makes as a “senior advisor” at News Corp. today. Barbara Byrd-Bennett was known in Cleveland as the “$300,000 wonder” by the end of her tenure running a 70,000-student district. In Texas, a handful of superintendents make more than $300,000 a year, including Spring Branch ISD’s Duncan Klussman, whose board bumped his pay to $305,000 earlier this year to run the fast-growing district of 35,000 students.

Besides universities—where tuitions and private donations help pay for top-shelf coaches and presidents—school superintendents are some of Texas’ best-paid public workers. Only top financial managers and lawyers earn more than the base salary for superintendents in Texas’ biggest and fastest-growing districts. Car and phone allowances, retention bonuses and performance pay help sweeten the deal—and take the edge off the criticism superintendents receive from their communities.

“Shaking things up is a very traumatic thing for school districts,” says Don Rogers, a former superintendent at Eanes ISD, west of Austin, who now heads the Texas Rural Education Association. The best-known disruptive supers have been in large urban districts, but Rogers says rural school boards occasionally hire a superintendent to make sweeping reforms and raise test scores. “You have these entrenched groups of folks that are kin to half the school boards. Sometimes they’re able to make some change, but it usually costs them their job.”

Joe Smith, who runs the school administration news site TexasISD.com, says schools that bring in a new superintendent hoping for miracles often get it backwards. “When you find people who have experience increasing test scores, they usually don’t have experience in finance,” he says. “Oftentimes, it is finance they need in order to increase test scores—they need more people, they need smaller classes.”

David Anthony was superintendent in Texas City in 1995 when he realized testing had changed his job. Anthony now heads the education advocacy group Raise Your Hand Texas, and spent 24 years as a school chief before that, most recently heading Cypress-Fairbanks ISD in Houston, the state’s third-largest district. Thanks to standardized testing, Anthony says, there’s far more information available for the public and the media to judge superintendents by, and a lot of confusion about what it means.

That confusion can even help districts fudge their stats.

Rod Paige, Houston’s superintendent in the mid-1990s, was one of the first to sell the public on his ability to raise test scores even without more money. The former college football coach trumpeted huge test-score gains and better graduation rates thanks to his leadership and the pressure of high-stakes tests. On the strength of those results, Houston won the prestigious Broad Prize for Urban Education in 2002, the award’s first year.

Paige’s “Houston Miracle” became George W. Bush’s “Texas Miracle” on the presidential campaign trail, and Paige parlayed his apparent success into an appointment as Bush’s education secretary. But after Paige left for D.C., academics picked apart his record, showing Houston had undercounted its dropouts and exempted low-scoring kids from taking the test, and even underreported crime and fighting in the schools. By then Paige was long gone, guiding national school policy.

Houston’s current superintendent, Terry Grier, came to the job with a reform package of his own, dubbed “Apollo 20,” a turnaround plan for 20 struggling middle and high schools. Grier’s plan is based on a “no excuses” approach inspired by popular charter schools. Under Grier, Houston ISD has once again seen gains in test scores and graduation rates, and Houston trustees awarded him a $115,000 performance bonus last year. In September, he accepted another Broad Prize on behalf of the district, which came with $550,000 in college scholarships in recognition of the district’s improving scores. But not everyone sees such a benefit in celebrating bumps in test scores.

John Kuhn, a superintendent in rural Perrin-Whitt school district west of Fort Worth (“Tyrant’s Foe,” February 2013), says that tying the superintendent’s job and prizes like Broad’s to test scores is a problem because tests become the single greatest measure of success. “The purpose here is to prepare students for life after school, and so student achievement is kind of this broad thing. Student test scores are a lot more narrow, and using that as a substitute is really kind of dangerous,” he says. “I’m not just talking about illegal activities but more subtle robberies of what the educational experience should be.”

Half of Texas’ 10 largest school districts include performance-based incentives in their superintendents’ contracts. Grier’s bonus total last year appears to be the highest. Fort Bend ISD’s Timothy Jenney earned $70,000 on top of his $260,000 base salary, before the school board bought out his contract last year. Austin ISD’s Meria Carstarphen is eligible for up to $25,000 a year in bonuses on top of her $295,000 salary. Those incentives aren’t limited to the state’s biggest districts.

El Paso ISD trustees hired Lorenzo Garcia in 2006 to help turn around their struggling district, where some schools faced possible shutdown under the provisions of No Child Left Behind. Garcia, who’d been superintendent at Houston’s Spring Branch ISD and a top curriculum official in Dallas before that, got $280,000 a year, plus tens of thousands in performance bonuses for raising test scores after just a few years. And then he got a federal prison sentence, after investigators learned his miracle turnaround was a fabrication (and that he’d steered contracts to his former mistress). Garcia’s top administrators, who’d gone on to lead other El Paso-area school systems, were fired or stepped down over concerns they’d replicated his scheme in their new districts.

Though departures are rarely that dramatic, about 200 Texas districts change superintendents every year. That’s about one in five, and it’s been pretty constant over the years, Joe Smith says. The average tenure for a superintendent is a little more than three years, according to a 2010 survey by the Council on the Great City Schools, a D.C.-based nonprofit. So when Michael Hinojosa left Dallas ISD after seven years as superintendent, it was virtually the end of a dynasty.

What Texas’ biggest school districts pay their leaders (click on a map dot for more details, or see it in a spreadsheet here)

Hinojosa had carried Dallas fairly steadily through years when brash school chiefs with dramatic reform plans came and went in other cities. He was a homegrown leader, a graduate of Dallas ISD’s Sunset High School, and during his tenure the district enjoyed modest academic improvement according to test scores and graduation rates. His most remarkable screw-up was financial: a $64 million budget shortfall in 2008 thanks to an accounting error and possibly hiring too many teachers. Later that year, then-Mayor Tom Leppert floated the idea of a mayoral takeover of the district—a school turnaround strategy that had been in vogue among big American cities—but quietly dropped the idea.

Hinojosa adopted a signature plan for the district called Dallas Achieves, which included the goal of winning the Broad Prize by 2010. When that didn’t happen, Dallas Morning News columnist Bill McKenzie urged the business community and “Democratic reformers” to get involved with Dallas’ schools, particularly to tie teacher pay to student performance. Though Hinojosa had overseen a rise in test scores and graduation rates, McKenzie and other shake-it-up reform advocates had plenty of ammunition against him. In 2011, less than two-thirds of Dallas’ high school graduates took SAT or ACT tests, and just 10 percent of those scored high enough to be called “college ready.” Almost half of Dallas’ students scored below grade level on state math tests.

After Hinojosa announced his departure, the business community took a new interest in the school system, giving tens of thousands to school board candidates who favored shaking things up—a remarkable departure from the election the year before, which was canceled for lack of challengers. Dallas—after seven years with Hinojosa, with schools in poor neighborhoods still struggling and with administrators who’d grown comfortable in their jobs—was finally ready for reform.

Mayor Mike Rawlings, who promised in his campaign to support bold improvement in the schools, told the Morning News, “You already have some momentum for change and have a school board taking reform-minded actions, and the city and business community is supportive of this, and whoever comes in will have a lot of support. For that reason, and if it succeeds, you’re going to be a hero.”

Rawlings, a former Pizza Hut CEO, said he was looking for a new superintendent who could be a “real change agent. It’s less important to me if they’re a mathematician or a businessperson or a military type. Their background is less important than their leadership ability.”

The business world’s interest in remaking public education is nothing new—calling school leaders “superintendents” became popular a century ago, when factory efficiency experts took a first pass at redesigning public schools.

America is enjoying another such moment today. Popular business literature is suffused with the idea that strong leadership has the power to improve even the most massive bureaucracy, and the education world has fallen in line. The George W. Bush Institute, the think tank tied to the presidential library at Southern Methodist University, is home to an “Alliance to Reform Education Leadership.” The Broad Superintendents Academy in Los Angeles is one of the most polarizing institutions of the current school-reform movement, grooming “exceptional leaders and managers to help transform America’s education systems, raise student achievement and create a brighter future,” according to its website.

“I think there’s been something of an infatuation with business management in education,” says Young, the University of Virginia scholar. “Schools are not businesses. We don’t necessarily have the same moral obligations to the community and to kids that you have to stakeholders that are investing their money.”

“The reason it works in business is you do have a bottom line,” Brewer says. “In order to do that in education, they had to find one indicator of success. That’s not necessarily compatible with the complexity of education.”

New superintendents who focused on “quick wins” in the “first 90 days”—that’s all straight out of popular business literature. So is the focus on transformational change, the faith that we’re capable of rapid improvement in society if only we’ll shake off the old ways and dismantle the status quo. No business concept has been more contentious in schools than the tech-inspired enthusiasm for “disruption.”

To find their new change agent, Dallas ISD’s trustees hired PROACT, an Illinois search firm that had recently found Carstarphen for Austin ISD. Superintendent searches have become big business in the past few years, and the Dallas school district paid $55,000 for the service, then another $200,000 to rustle up more administrators and principals.

The search for Miles took seven months, ending with a surprise announcement in April 2012. He had spent 17 years in schools, beginning as a 9th-grade teacher in the Colorado district he graduated from, but his background prior to that was remarkable. He’d been an Army Ranger, an intelligence officer and then a diplomat in Poland and Russia. In 2004 he ran for a U.S. Senate seat in Colorado, losing in the Democratic primary to Ken Salazar. During the campaign, he explained his opposition to the Iraq war, which he acknowledged was rare among West Point graduates like him. “My whole life has been kind of an exception,” he said. By 2010, when he ran the Harrison School District in Colorado, the local press had caught on to his winning personal story. The Colorado Springs Gazette described him as a “complex man: intense but calm; warrior and poet.” Recalling the plane crash that nearly killed him in the Army, Miles seized on another Hollywood touchstone. “It’s like Private Ryan,” he said. “I’m here by fate, and I have to earn my second chance.”

Miles was largely unknown in Texas, but news stories announcing his selection quickly drew anonymous comments from people claiming to know him or work for him in Colorado, bidding him good riddance and calling him “a real snake oil salesman—sorry that he’s charmed your board.” It’s an unscientific measure of community sentiment, but it was a first taste of the online vitriol Miles would attract in Dallas—far more than Hinojosa ever drew.

By the time Miles was named superintendent in Dallas, the backlash to iconoclastic urban school reformers had matured. Critics were ready to spot parallels between Miles and disruptors who’d shaken up big-city districts elsewhere, like Rhee in Washington, D.C., and Klein in New York. Miles sure spoke like one of them.

“Sadly, in our profession, there is a lack of leadership and courage,” he told EdNews Colorado shortly after being named a finalist in Dallas. “You try to make a huge change, and you’re going to get vilified by at least a small portion of the community, if not a large portion of the community, that’s why people don’t do this work.”

His signature reform in Colorado was a teacher performance-pay system, and he said one of the reasons he was drawn to Dallas was that it seemed ripe for reform. “A transformation is needed,” Miles wrote in his “Destination 2020” plan, “and time is against us.”

Though Miles had experience in the classroom and had worked his way up quickly, critics saw his rapid rise and his enthusiasm for systemic change as evidence that Miles was another Rhee, someone who’d spend a couple years tearing the place apart before moving on to the speaking circuit or some consulting business. Miles, in fact, already had a consulting firm, called Focal Point, which sells what its promotional materials refer to as “Educational Leadership for the 21st Century.”

Dallas ISD trustees offered Miles $300,000 annually, plus $50,000 a year in “deferred compensation” to stay with the school district, and performance bonuses of up to $200,000. His first move was to reorganize the district’s top leaders, assembling a cabinet of 12 top officials, which he began signing to generous contracts. Most controversial was his new communications officer, Jennifer Sprague, whom he lured from his old Colorado district for $185,000 a year. In response to critical media coverage of Sprague’s high salary, Miles suggested reporters were being sexist.

Critics of tear-it-down-to-build-it-up school reform feared for Dallas’ schools, and Miles did little to assuage their fears. He had schools to transform.

You come into a district talking about graduation rates and academics, and you leave getting yelled at about money and layoffs. That’s how it typically goes when a superintendent gets forced out, says Mike Moses, a former Texas education commissioner and Dallas superintendent who now leads a superintendent search firm.

“Seventy percent of the adult population do not have school-age kids,” Moses says. “So what are they watching? They’re watching how you handle their money. I see more people that get into trouble with mismanagement of money and mismanagement of people.

“The thing about an urban district you’ve got business politics, you’ve got labor politics, you’ve got ethnic politics, you even have some media politics. You’ve got a lot of people tuggin’ on the superintendent in a lot of different directions,” Moses says. “People have to approach the job respectfully and humbly.”

The attitude a superintendent brings to the district has a lot to do with how long he or she sticks around. And stability can do a lot more for schools than a few isolated years of big reform. That’s a lesson Dallas is learning.

On the last day of September, a year after he debuted with the balloons and the movie clips, Miles sat quietly in the Dallas ISD boardroom. A frosted-glass nameplate lent his seat at the table a misleading sense of permanence as the trustees voted on whether to fire him.

“We have certainly had disruption this past year,” said DISD trustee Lew Blackburn. “I don’t think that disruption is necessary for change.”

That’s a thought that seems to be gaining traction nationally, just a year after Dallas went all-in for disruption. The enthusiasm for non-traditional superintendents, for instance, is waning. “Ten years ago, the top 10 school districts were run by non-traditional educators. That’s not the case anymore,” says Dan Domenech, executive director of the American Association of School Administrators.

Miles’ first year in Dallas was a nasty one. One-quarter of the district’s principals were gone after that year, including some favorites in South Dallas and Oak Cliff, where schools earned high marks from the state. Their departures sparked a fight with black community leaders like Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price, who circulated a letter to pastors accusing Blackburn of taking Miles on a goodwill tour of black churches to sell his reforms. “Pontius Pilate plans to parade through many of your churches with a fake Jesus in tow,” Price wrote. Miles’ communications chief, Jennifer Sprague, left before Christmas, and her replacement came and went after just a few months. Other top officials fled the district, including holdovers from the Hinojosa years and some of Miles’ new recruits.

Protesters picketed near Miles’ home during his son’s 12th birthday party with signs reading “Dictator” and “MMG: Mike Miles Must Go.” In August, Miles’ wife and son returned to Colorado, complaining of the media attention, but Miles stayed put.

A week before the school board voted on Miles’ job, the Foundation for Community Empowerment—a group headed by former Trammel Crow Company chairman Don Williams—released a series of academic studies it had commissioned that were critical of Miles’ reforms. “We believe the current Superintendent lacks the pedagogical, leadership and integrity qualities necessary to lead Dallas ISD and recommend the Board terminate his contract,” Williams told the Morning News.

One of those studies of Miles came from University of Texas at Austin researcher Julian Vasquez Heilig, who described Miles as a “trickle down” reformer who takes a heavy-handed, prescriptive approach to teachers.

Teachers complained about Miles’ requirement that they keep their doors open, and about the frequent in-class evaluations from administrators—the same things that set off Miles’ teachers in Colorado Springs. He established a $5 million leadership academy within the district to groom principals and, in effect, reward teachers who bought into his approach. His long-awaited performance-pay system for teachers, still in the works, will likely have the same effect.

But it was ethical issues that prompted Dallas trustees to take a vote on firing him: allegations that he tried to steer a contract to a company of his choice, intimidated the communications officer who complained about it, then interfered in an investigation into his behavior with her. The fight leading up to the vote wasn’t about the enemies he made firing principals or managing teachers, but when the opportunity arose, those enemies were glad to pile on.

Even if his reforms were unpopular, they mirror much of what Grier has been doing in Houston—with a less rancorous school board and far less anguish around the city. For a superintendent, what you say may be less important than how you say it.

At a school board meeting the week before the board voted on firing him, Miles quietly recalled the support he’d gotten from community members urging him to stay the course. “We’re in a real story that matters,” he said. “And while the script may have been drafted, the final scenes have not been shot.”

Blackburn joined the board’s two other African-American members in voting to let Miles go, but the board’s five other members, all white, voted to keep him. (Incredibly for a district that’s nearly 70 percent Latino, Dallas has no Latino school trustees.) Miles kept his job.

Dallas ISD will get to 2020, whether or not “Destination 2020” does any good. Now that he has a reprieve from the board, Miles might even lead the schools there himself. Maybe years from now his name will grace the basketball arena where school employees will get to meet their next superintendent. Maybe he will be remembered as a hero. But not if he has another year like this one.

You can’t improve a school district if you only last a couple of years. School chiefs who ride into town with a hero complex, alienate everybody and get dragged out like martyrs don’t get to build a legacy.

Joe Smith of TexasISD.com believes the hero trend is falling out of favor. “We’ve gotten to the peak of that movement, and I think we’ll see the pendulum come back,” Smith says. “If you’re looking at redefining your schools in your community, I would think that someone who knows the community would have a jump on anybody else.”