Ted Cruz Won Because of Rural Texas, but Beto Made Small Gains for Democrats

O’Rourke’s strategy of hitting all 254 counties didn’t win him the race, but it likely gained Democratic ground in small-town Texas, Republicans’ most reliable stronghold.

At first glance, it would appear as if Democrats were dealt a series of miserable defeats in rural Texas Tuesday.

Beto O’Rourke, who spent beaucoup time and money to campaign in all of Texas’ 254 counties, won only 32 of them in his bid to oust Ted Cruz. While Texas Democrats saw major gains in larger, typically red urban and suburban counties like Tarrant, Williamson and Fort Bend, they failed to flip any reliably Republican, rural counties. In congressional and state legislative races in small-town Texas, Republicans handily won by the usual lopsided margins.

But digging in a little deeper, it appears that O’Rourke made small, but measurable gains in rural counties compared to Hillary Clinton and Wendy Davis, despite winning very few of them outright. O’Rourke’s campaign was centered on a 254-county strategy, and he regularly drew surprisingly large crowds to his town halls in some of the most conservative rural enclaves in Texas, places where Democratic voters often feel they have to hide their political affiliation.

On average, outside the state’s 30 most populous counties, O’Rourke performed 2 percentage points better than Democratic gubernatorial candidate Wendy Davis in 2014, according to an Observer analysis. While Davis picked up about 22 percent of the vote in those counties — home to 5.8 million Texans — O’Rourke got 24 percent. Hillary Clinton pulled 23 percent of the vote in those counties in 2016, the analysis shows.

In Nacogdoches County, where Davis got 24 percent in 2014 and Clinton garnered 30 percent, O’Rourke pulled 36 percent after visiting the town several times. In much smaller Bailey County, where a woman attending a Muleshoe town hall interrogated him about gun rights and rattlesnakes, O’Rourke nearly doubled Davis’ performance, pulling in 25 percent of the vote. In Abilene’s Taylor County, Beto won 26 percent of the vote compared to Davis’ 17 percent and Clinton’s 22 percent.

O’Rourke moved the needle from the last midterm by 4 percentage points in both Lampasas County, where he packed an event beyond capacity in August (and was heckled by a Trump supporter) and in Cooke County, where O’Rourke said he ate “the best fried pies of my life.” He also saw a 4-point increase in Kerr County in the western Hill Country.

But pockets of rural Texas — some in the Panhandle, West Texas and along the Gulf Coast — resisted Betomania and shifted further right on Election Day compared to 2016. For instance, Dallam County, at the Panhandle’s far northwestern corner, and nearby Castro and Cochran counties, favored Clinton over O’Rourke by a few points.

The overall boost in rural counties helped O’Rourke by thousands of additional votes, though Cruz piled on votes, too, since voter turnout was up across the board. Like O’Rourke, other statewide candidates on the Democratic ticket failed to turn rural Texas blue, but gains in those areas may have helped them get surprisingly close to beating Republican incumbents.

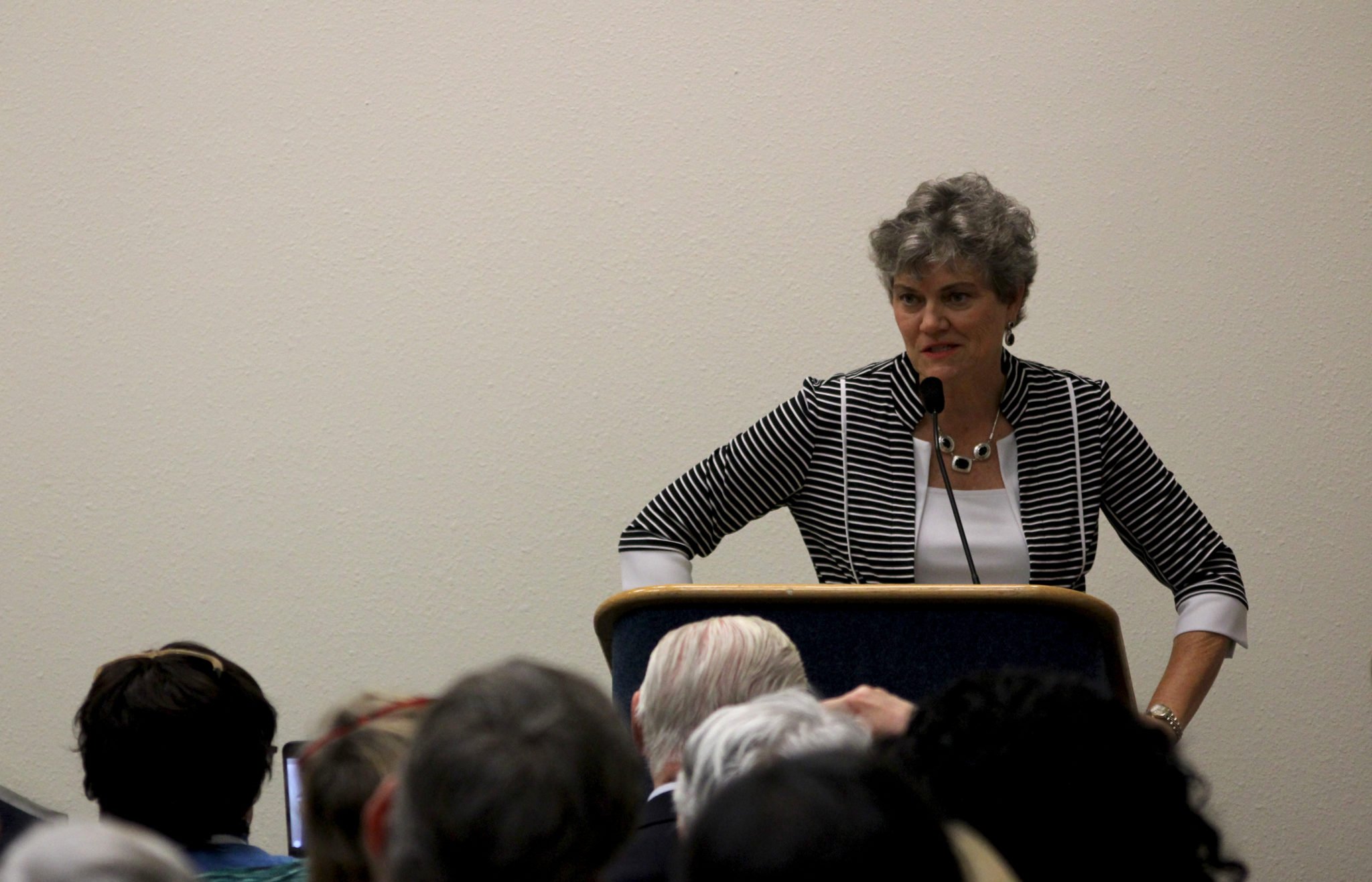

With results nearly mirroring O’Rourke’s, ag commissioner candidate Kim Olson, who had little name recognition, came within 5 percentage points of beating Sid Miller. Mike Collier, who ran for lieutenant governor, and Justin Nelson, the Democratic candidate for attorney general, also ran surprisingly tight races against incumbents.

Aside from O’Rourke and Olson, none of those Democrats — or the state party — put much effort into campaigning in rural Texas. At the party’s convention in Fort Worth this summer, Democrats barely talked about rural parts of the state at all, and when they did, the bare-bones strategies they offered felt anemic and vague.

Even if Democrats do only somewhat better in small towns, that would be bad news for Republicans running statewide, who were slaughtered in the five major metros and ceded a shocking amount of ground in suburban counties.

Still, down-ballot Republicans in rural Texas did just fine. Drew Landry, a professor at South Plains College near Lubbock, got beat 78-21 by incumbent state Representative Dustin Burrows. That race was pretty much par for the course for down-ballot Democrats: State Representative John Smithee, another Panhandle Republican, steamrolled his opponent. Congressman Mike Conaway, who chairs the U.S. House Agriculture Committee, kept his West Texas seat without breaking a sweat. So did Jodey Arrington, who also sits on the committee.

In rural East Texas, the cartoonishly “out-there” U.S. Representative Louie Gohmert trounced a Democratic challenger by about the same huge margin as in 2014 and 2016. A little further south, Republican Congressman Kevin Brady did the same. Democrats didn’t even bother running a challenger against state Representative Matt Schaefer, one of the fringiest characters at the Legislature and a member of the far-right Freedom Caucus. Dade Phelan, a state Representative from southeast Texas who also won an unopposed race, wrote on Twitter Wednesday morning: “[Once] again rural Texas saves the day for many GOP statewide candidates.”