Growing Up a Texas-Mexican Woman

In a new book celebrating Tejanas in literature and art, Laura M. Lopez muses on memories that carry culture and identity from one generation to the next.

A version of this story ran in the May 2016 issue.

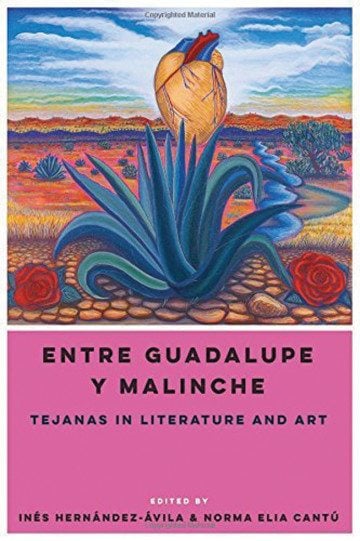

The recently published Entre Guadalupe y Malinche: Tejanas in Literature and Art is a collection of work by women who identify as Tejana. Many of the writers and artists are veterans of the Chicana movement of the 1960s and 1970s, when, as co-editor Inés Hernández-Avila writes, “there was an incredible cultural and artistic energy that swept through the state, emerging from the land and the people themselves yet intensifed from the four directions by other movements for social justice in the Americas and, indeed, the world.” This excerpt is about memories that carry culture and identity from one generation to the next.

In South Texas, August is the hottest month of the year, when the heat and humidity can kill a person if one is not adequately prepared for them. It was during this hottest month in 1947 that Margarita Valdez was born to her parents in San Antonio. The experiences and struggles in her life have been long and hard, experiences that had her married at 19, mother of three by 25, and divorced by 29. Throughout most of the years of her marriage, she was physically and emotionally abused by her husband. After a rather bitter divorce and custody battle, she was left alone to financially and emotionally support three young daughters with a minimum-wage job as a nursing assistant and with minimal child support. It is difficult for single mothers with only a high school education and few job skills to raise three young children on a minimum-wage income — and it is even harder if you are a Mexican or Chicana living in South Texas.

Edited by Inés Hernández-Ávila and Norma Elia Cantú

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

501 pages, 38 photos;

$90 (HARDCOVER) University of Texas Press

I cannot account firsthand for the time when my mother Margarita López was the girl Margarita Valdez, but through the years I have constructed a vision of this young person from a multitude of photographs, stories from my grandmother, and talks with my mother about her “old life.” My mother grew up the middle child of Texas-born Mexicans who relocated to San Antonio during the latter years of World War II. Both of my mother’s parents came from rural parts of the Rio Grande Valley, have never spoken “proper English” and had at most third-grade educations. When my mother was growing up, my grandparents often held two or even three low-paying jobs each, leaving my mother, her older sister, and their younger brother under the care of extended family when they were not in school.

Until high school, both my mother and her sister were educated by the nuns at San Fernando Catholic School, under whose influence my mother almost became a nun herself. In fact, she was a novice for a few years, but she claims that she came to the conclusion that it was not her calling. She would remind my sisters and me, “If I had become a nun, you and your sisters wouldn’t be here today,” which always made me feel that my existence was quite subject to the hands of fate. I know little of the time when she went to high school, except that she met my father there and married him soon after graduation. When I was a little older, I asked her why she had married my father so soon after high school (i.e., if she had perhaps waited she could have avoided a bad marriage). She replied that she loved him at the time and that marriage was the only way she could leave her parents’ house. As Gloria Anzaldúa observes, there used to be only three directions a Chicana could turn to when she wanted to leave her parents’ home: to the Church as a nun, to the streets as a prostitute, or to the home as a mother. These had been my mother’s choices as well.

My grandfather worked most of his adult life as a yardero or groundskeeper for the VIA Metropolitan Transit System in San Antonio and, since I spent many afternoons and weekends at my grandparents’ home, I saw him come home after many hours spent toiling under the hot Texas sun. He was rather light-skinned or güero due to our German Spanish ancestry, and the sun turned his exposed skin permanently red. He would come home, eat the dinner my grandmother had ready for him, and then sit in front of the television as he joked about the guys at work and criticized the “big wheels” (i.e., his white male supervisors). My grandfather had always been a blunt man, and my grandmother would often be embarrassed when people would come over to their home because no one knew what he was capable of saying to them. My sisters and I jokingly called him the Mexican Don Rickles, an old comedian who was very funny, often at the expense of others. Still, my grandfather was an amazing man because he could still laugh and joke about his experiences despite all the hard work, struggles, and suffering he had in his life. One of my favorite photographs is one in which my mother, at about eight years old, is pictured standing in front of my grandfather. His arms encompass her small frame, and she has a huge smile on her face as if she had no cares in the world.

My grandmother, a strong and spiritual woman, learned to struggle at an early age. The youngest in a family of ten, she was just a child when she picked cotton or whatever crop was in season alongside other migrant farm laborers in the heat of the South Texas sun. Later, as a young woman in San Antonio, she worked mostly in factories. She shelled pecans, the industry where just six years earlier Emma Tenayuca had led protests for labor and wage reforms, she worked steam machines in the laundry industry, and she cleaned fish fresh from the Gulf of Mexico. She worked on and off at these various jobs until she was in her late 40s, except for a short hiatus when my uncle was born in ’59.

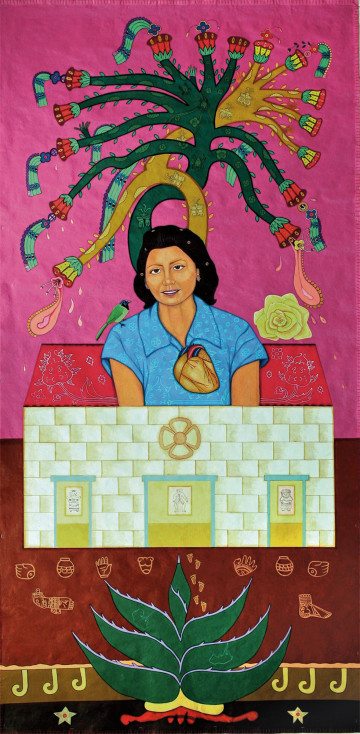

Shortly after his birth, he became very ill with a fever that caused brain damage and led to severe epileptic seizures for many years. I remember my grandmother telling my sisters and me that Uncle Frank almost died during that time, but she prayed and prayed to the Virgin Mary and, by a miracle, he was brought back to life. As soon as his condition was no longer life-threatening, my grandmother traveled to San Juan and, like thousands of other devout followers, paid homage to La Virgen by crawling on her knees from the church doors to the altar that stood many yards away. That story always amazed my sisters and me, especially because my grandmother told it with such great emotion and faith. She has always kept an altar to La Virgen de San Juan in her bedroom and prays every morning and evening for the safety and care of her family.

Ever since I can remember, my mother and grandmother consulted curanderas for different problems they faced in their lives. They exhibited great faith in the power of these curanderas, whether they were seeking a special hierba (herb) for a stomach pain, a limpia (cleansing) for all the mal de ojo (evil eye) that people gave them during the week, a card reading to see if perhaps someday their daughters would get married or come into money, or, God forbid, a major trabajo (job) that needed to be done because even the Anglo doctors could not help with this curse. We went often to Perez’s Botánica (a curandero “pharmacy”) on the west side of San Antonio, but usually we had to travel to someone’s house. Because curanderas have a large clientele in San Antonio, my mother and grandmother would wait patiently while people who arrived before them were taken care of one by one in private consultation. My sisters and I would play outside on the front porch waiting for them to finish with the curandera. Our Americanization and my own Western skepticism made it difficult for us to believe in the practices of these curanderas, especially when some of these curanderas charged large sums of money for trabajos that seemed to promise modern-day miracles.

For a period as a child, I was embarrassed by the voices of my grandparents and mother when they spoke, and spoke loudly, in public places. I wondered why they could not speak “proper English,” like what I heard in school from my teachers or read in books. As an adult, those early thoughts anger me as I recognize the culturally hegemonic forces that caused me to feel this way in the first place. When I was growing up, the language most used by my family was Tex-Mex or “Spanglish.” Because my grandparents had very little formal education and are second-generation Tejanos, their language is more heavily Spanish-influenced. My mother’s is more English-influenced largely because she was kept from speaking Spanish during her formal education. By the time I went to school in the mid-1970s, there was little need to use corporal punishment to regulate Spanish use in school. The Texas education system had “taught” our parents well enough. The only time I ever heard Spanish in school was from the ESL students, who were few, alienated, and removed from our regular classes. As a child, I did not even realize that my ancestral language had been stolen from me. Any time I had to converse with native Spanish speakers, I felt culturally deficient. I could understand what they said to me because I heard Spanish often in my grandparents’ home, but I could not speak back with “proper Spanish.” As an adult, I had to pay for classes to brush up on my Spanish in an effort to reclaim my ancestral language.

For the women in my family, work outside the home was a necessary part of the struggle to survive and care for one’s family. My great-grandmother worked in the cotton fields of South Texas all her life before she succumbed to ovarian cancer in her late 30s. As described earlier, my grandmother worked hard most of her life in both the agricultural and manufacturing labor markets. My mother began working full-time when she divorced my father and had to raise my sister and me.

I remember my grandmother telling my sisters and me that Uncle Frank almost died during that time, but she prayed and prayed and by a miracle, he was brought back to life.

Many nights I saw my mother come home tired and frustrated from a job that held few incentives in return for the physical and psychological demands it placed on her. Yet she knew that she had few alternatives and that she had to care for three young children. I observed and learned from her efforts and the strength she showed despite the oppressive nature of her predicament. My mother, who learned from a long line of working Tejanas before her, taught me these survival skills.

The Texas education system had “taught” our parents well enough. The only time I ever heard Spanish in school was from the ESL students, who were few, alienated, and removed from our regular classes.