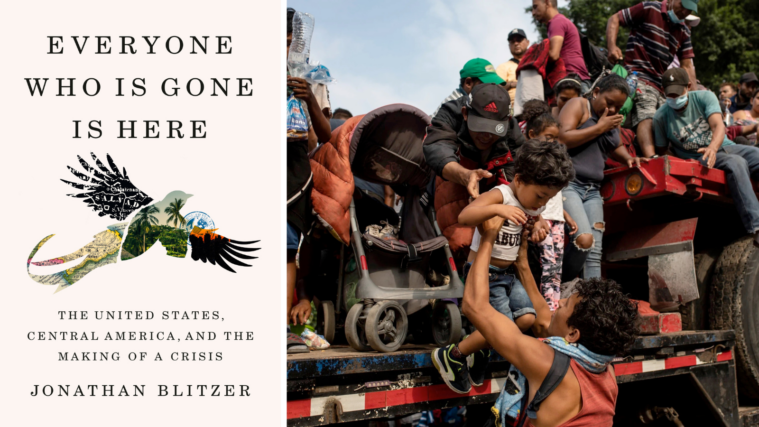

Valeria Luiselli’s ‘Tell Me How It Ends’ Is the First Must-Read Book of the Trump Era

The Mexican novelist writes that asylum-seekers come to the U.S. not in search of the American dream, but “to wake up from the nightmare into which they were born.”

by Valeria Luiselli

COFFEE HOUSE PRESS

$12.95; 104 pages

Over the past two months, stepped-up immigration raids and arrests have terrorized U.S. immigrant communities. At the same time, ongoing attempts at the state and federal level to dislodge so-called sanctuary city policies in Texas and elsewhere indicate more actions to come, perhaps including an attempt to follow through on President Trump’s campaign promise of large-scale deportations. With compelling stories of detained individuals and separated families in the headlines, many Americans are seeking to learn more about the harsh realities of the U.S. immigration and asylum system. Thankfully, there is now an obvious place to direct readers: Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in 40 Questions, the new book-length essay by Valeria Luiselli.

Luiselli, a Mexican-born writer living in New York City, has risen to prominence over the past five years. In 2012, she appeared on the Spanish-language scene with a collection of linked lyric essays, Sidewalks (Papeles Falsos), a breezy, highbrow-name-dropping meditation on nationality and belonging. That same year, Luiselli released a first novel, Faces in the Crowd (Los Ingravidos), which pulled off a thrilling synthesis of Latin-American traditions, melding magic realism with the more contemporary Roberto Bolaño-esque flavor of gritty urban intellectual escapades.

As her works have been translated into English, Luiselli has become one of the most internationally recognized voices in Latin-American literature — although, in part because of her globe-trotting upbringing as the child of a diplomat, it might be more appropriate to think of her as a member of an international generation. In Sidewalks, Luiselli wrote of the notion that, “literature could be like a great house, a territory without frontiers that offers shelter to those of us who don’t know how to inhabit any particular place.”

These days, frontiers are reasserting their prominence. Perhaps in response, Luiselli has shifted her register dramatically with Tell Me How It Ends, capturing the mood of the era: warily observational, tragic, with a sense of walls closing in.

Tell Me How It Ends is based on Luiselli’s experiences as a volunteer interpreter in federal immigration court in New York City. The book is organized around the 40-question intake interview that volunteers administer to each new child asylum-seeker. As the questionnaire unwinds — from “Why did you come to the United States?” to “Did anything happen on your trip to the U.S. that scared you or hurt you?” and “What do you think will happen if you go back home?” — the reader slowly begins to grasp the impossible choices facing migrant children and their families.

Though the number of unaccompanied Central American minors detained upon arrival in the U.S. dipped in 2015, it appears to have returned to crisis levels in 2016. “It is perhaps not the American Dream they pursue, but rather the more modest aspiration to wake up from the nightmare into which they were born,” Luiselli writes.

Instead of villainizing the children who risk so much to come here, welcome them as the refugees they are.

From this perspective, it’s clear that further immigration crackdowns, especially on asylum-seekers, will only serve to extend the nightmare and more deeply entrench the cycle of violence from which migrant children hope to escape. Though Luiselli does not engage Trumpism at much length in the text, her book offers a timely and compelling moral alternative: Instead of villainizing the children who risk so much to come here (by one measure, 80 percent of women and girls who cross from Central America to the U.S. are raped along the way), welcome them as the refugees they are. Each child saved is one fewer recruit for an organized-crime catastrophe that has arisen in large part because of failed U.S. drug enforcement schemes and past bloody intrusions in Central American political conflicts.

In this sense, the book can feel like an ACLU report written by a world-class literary stylist. But Tell Me How It Ends is also a personal record of Luiselli’s coming into a new sense of her own nationality. Her green card is delayed, and she, who once briefly became a legal resident of Venice, Italy, on a whim to save money on a doctor’s appointment, must now quit teaching so as not to run afoul of U.S. immigration authorities. Never before, it seems, has this child of the globalist era felt so Mexican. In a moment of personal reflection, Luiselli allows herself to wax poetic: “I’ve had to ask so many children: Why did you come? Sometimes I ask myself the same question. I don’t have an answer yet. Before coming to the United States, I knew what others know: that the cruelty of its borders was only a thin crust, and that on the other side a possible life was waiting. I understood, some time after, that once you stay here too long, you begin to remember the place where you originally came from as a backyard might look from a high window in the deep of winter: a skeleton of the world, a tract of abandonment, objects dead and obsolete. And once you’re here, you’re ready to give everything, or almost everything, in order to stay and play a part in the great theater of belonging.”

At such moments, Luiselli’s book transcends its subject matter and becomes worthy of inclusion in a great American (and international) canon of writing about migration. But to read Tell Me How It Ends only in that way is to miss the point. Luiselli is not, in this book, much interested in transcending anything, or in her own admission to the great house of immortal literature. These days, reality is more urgent. The fate of thousands of children is at stake. And as they slip through the cracks, so does the future of a people, a continent and a nation — whichever one it is that we imagine we belong to, the children and Luiselli and her readers too.